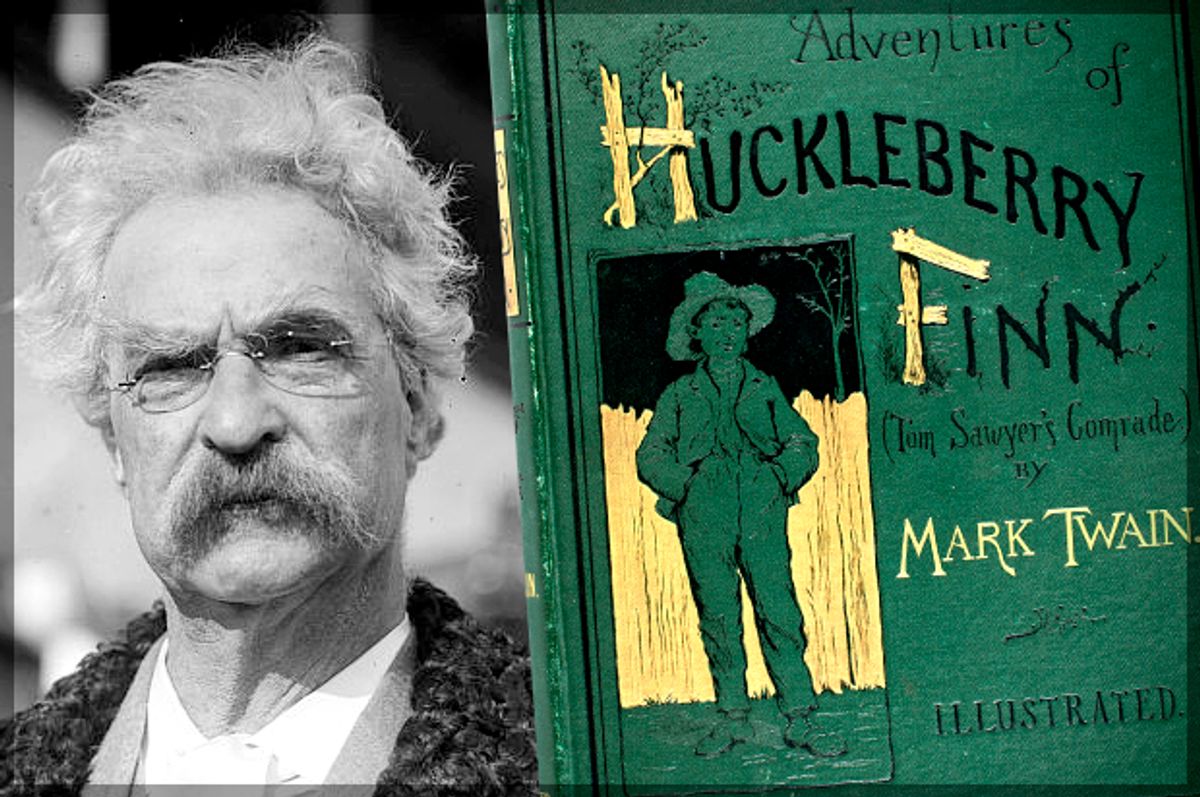

"A committee of the public library of your town have condemned and excommunicated my last book," Mark Twain wrote to the secretary of Concord Free Trade Club in 1885, "and doubled its sales." The book that was the object of what Twain called "this generous action," was "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn," a novel that would go on to be banned here and there in schools and libraries for the next 130 years.

Today, "Huckleberry Finn" is most often banned for its use of the N-word. (If there's an argument for the legitimacy of Twain printing it, I can't imagine one to justify its appearance in a humble book review, so I'll be euphemizing it here.) But that came later; the book would not be censured for containing "passages derogatory to negroes" until 1957, when it was removed from the curricula of elementary schools in New York. Rather, disapproving librarians and critics in the late 19th century deplored "Huckleberry Finn" as "the veriest trash" for its favorable depiction of "a wretchedly low, vulgar, sneaking and lying Southern country boy." And for its violence, which is considerable.

This is not to say that the Concord library committee wasn't offended by the N-word back in 1885; it probably was. Avoiding offense, as Andrew Levy explains in his provocative new book, "Huck Finn's America: Mark Twain and the Era that Shaped His Masterpiece," was one reason why Twain removed the word from the readings he did during a cross-country tour that year with fellow writer George Washington Cable. Cable persuaded Twain that it would be inexcusably "gross" to utter it before "the most thin-skinned and supersensitive and hypercritical matrons and misses," that is, genteel white women who considered the N-word to be coarse speech.

"Huck Finn's America" is about the context in which "Huckleberry Finn" first appeared and, eventually, how that context has shifted -- or not. Levy's overarching argument is that we misunderstand American culture in fundamental ways because we habitually forget our own past in favor of happy, gauzy nostalgia and/or fantasies of progress. Above all, we don't appreciate a phenomenon that would come to disgust and dispirit Twain late in his life: "It's not worthwhile to try to keep history from repeating itself," the author wrote in a notebook, "for man's character will always make the preventing of the repetitions impossible." Levy is not quite so hopeless, but he thinks we have a better chance of actually changing things if we admit that we keep having the same arguments and revelations over and over again.

In researching "Huck Finn's America," Levy immersed himself in newspapers and magazines from around the time Twain's novel was written and published. What he found was that nobody, including Twain himself, considered race to be the primary theme of "Huckleberry Finn." Rather, the novel emerged from and spoke to a society that was obsessed with wayward children, particularly boys, and most typically lower-class boys spurred to delinquency by the violent stories they read in dime novels. The papers were full of "stories of children committing crimes or dying young or killing each other," to a degree that, Levy remarks, a modern reader would find "simply numbing." In response to this perceived crisis, Americans were, for the first time, seriously discussing the establishment of a system of public education.

Even before he wrote "Huckleberry Finn," Twain was needling the attitudes behind this panic. Tom Sawyer is exactly the sort of boy who reads sensational adventure stories and makes them fodder for endless mischief. Twain himself hated school, found it boring, oppressive and claustrophobic, and encouraged his own daughters to read by reverse psychology; he and his wife, Olivia, withheld English-language books from them until the girls, their interest piqued, went behind their parents' backs and taught themselves to read in less than two weeks. Their father nearly burst with pride. Twain especially despised the pious, moralistic children's literature of his time, and wrote parodies with titles like "The Story of the Bad Little Boy That Bore a Charmed Life" and "The Story of the Good Little Boy Who Did Not Prosper."

"To him," Levy writes, "bad words were good; popular or polite ideas were bad." "Huckleberry Finn" is, after all, about two runaways: One is the slave Jim and the other is Huck, who flees both an abusive father who treats him like a possession and the well-meaning Widow Douglas, who wants to "sivilize" him. In the imaginations of Twain's Victorian audience, Levy writes, Huck and Jim were similar and linked, with the figure of "the bad boy of America," as the newspapers called this new menace, conceived as "a kid who could not be civilized even though he was growing up in the middle of a civilization." By making a hero of such a boy -- with his slackerish attitude, his deplorable habits, his vulgar language and his steadfast refusal to settle into respectability in the end -- Twain was, in the eyes of his contemporaries "more radical talking about children than talking about African-Americans."

That's not to say that Twain didn't hold unusually progressive views on race. He claimed an "exquisite Mongrel" heritage, including African ancestry, when speaking to the New England Society and privately he said that he blamed whites for nine-tenths of any bad action on the part of an American "Negro." But Levy juxtaposes the mocking, elusive, satirical Twain with Cable, a writer initially celebrated for his depictions of the Creole culture of New Orleans, in which he was raised. While Twain and Cable were playing to enthusiastic crowds in their "Twins of Genius" tour, Cable published an essay, "The Freedman's Case in Equity," that straightforwardly called for racial integration. For this, he was embraced by black Americans in a way Twain wasn't. (Levy could find no contemporaneous reviews of "Huckleberry Finn" in the nation's robust black press.) Cable was ostracized by white Southerners, and his literary career never entirely recovered.

Twain might have advanced similar ideas, but he did so, as Emily Dickinson would put it, "slant," and his popularity only boomed as a result. Levy portrays the author as trickster who donned a series of disguises, beginning with the moniker "Mark Twain" itself, and who used humor to prod the complacency and obliviousness of conventional society. Comedy also helped him sidle up to and away from bald statements of conviction like Cable's. What modern-day Americans regard as the emotional and moral climax of "Huckleberry Finn" -- the moment when Huck decides that he will help Jim even though he has been taught such behavior is wrong and will land him in hell -- Twain's contemporaries seemed to regard, to quote one reviewer, as merely "amusing."

Similarly, Levy argues that minstrel shows, about which Twain was profoundly ambivalent, had a far greater influence on "Huckleberry Finn" -- and, in fact, on all of American culture -- than anyone wants to acknowledge. Twain had loved the shows as a boy, when the tradition was new and at its most anarchic, when white men pretending to be black expressed a more unstable mixture of contempt and love. Later, as minstrelsy became more and more frankly racist, Twain repudiated it, but its initial disreputable irreverence remained close to his heart, as did the underlying idea of racial playacting.

The "Twins of Genius" tour featured set pieces in which Twain performed conversations between Huck and Jim, taking great care to reproduce the dialect of the black slaves he knew in his youth in the 1840s. Levy asserts that to this day most of American popular culture remains "a complicated amalgam of racism and identification," and "refigured minstrel practices remain profitable as long as they remain invisible, and they remain invisible as long as historical minstrelsy can be regarded as something intrinsically different from contemporary practices."

It's easier to look back at the public conversation about bad boys when "Huckleberry Finn" was published and recognize it as an early incarnation of conversations we have right now. "Condemning the newest media because it markets violence to children is one of the oldest tropes in American politics," Levy writes. "We forget that reading was the Xbox of the Victorian age, and dime novels their equivalent of violent video games," but being reminded of this repetition is not that troubling.

Race is another matter. Levy believes that Twain arrived at a conclusion that most Americans refuse to entertain. Huck might have experienced an epiphany about his kinship with Jim, but the novel ends with Tom Sawyer using both of them, and their lives, as a form of entertainment, then paying off the long-suffering Jim with the symbolically fraught sum of $40. Not much has changed in the course of "Huckleberry Finn" beyond the understanding of one wild heart, and that, as Twain himself realized in his old age, looking back on the failure of Reconstruction and railing about colonialism and King Leopold, does not actually amount to much. "Mistaking a dark comedy about how history goes round for a parable about how it goes forward is a classic American mistake," Levy observes.

Levy, an excellent, aphoristic writer, often emulates the prevarications of his subject. At times the argument he's making is as slippery as a bar of wet soap. While "Huck Finn's America" begins as an assertion that Twain's masterpiece is a book about childhood more than a book about race, in its final pages it rips off the mask and seems to present a truer face. If we, Levy insists, could understand what Twain has to say about childhood, which is that we've not made as much progress as we think, then we'd finally hear what he has to say about race, which is that we've not made as much progress as we think. And if we did that, "we might assume less often that a symbolic moment of cross-racial outreach -- watching a movie, listening to a song, making a private decision, even casting a vote -- substitutes for substantive change."

Shares