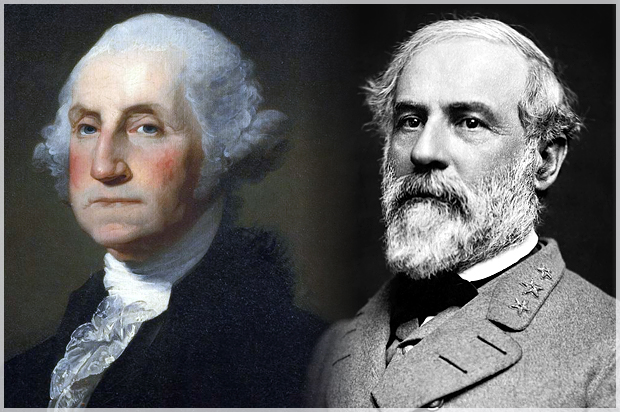

The cadets at West Point might not have nicknamed Robert E. Lee the “Marble Model” had they seen the statue of George Washington in the rotunda in Richmond. Here was a real marble model. On April 23, 1861, as the fifty-four-year-old Lee looked up at the figure, he could see how his fellow Virginian had appeared around the same age. By that time in his life, General Washington had won the Revolutionary War and made the historic decision to surrender power to civilian authority. Now the man who would not be king, as rendered by the sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon, stood on a pedestal beneath the round skylight crowning Virginia’s capitol dome. Under his left hand lay thirteen rods, bound like the thirteen colonies themselves. A sword, no longer needed, dangled to the side. His body, stretching more than six feet from head to heel, faced away from the closed chamber his admirer waited to enter. If the men meeting behind those doors had their way, Lee would pick up the sword, cut the cords tying the rods, and secure Virginia’s independence anew.

The delegates to the state convention had requested Lee’s attendance at noon on this day. They had recently approved an ordinance removing Virginia from the Union. The vote transformed the Potomac River, whose banks generations of Washingtons and Lees had called home, into a fault line. “Will the present line of separation be the permanent one?” Lee now asked aloud. How often, when back home at dear Arlington House, he had admired the Potomac view: the current whisking past the Virginia hillside; the Washington Monument’s unfinished shaft rising on the opposite bank; the columns atop the United States Capitol awaiting their dome in the distance.

Only five days earlier, Lee had crossed the Potomac for a meeting in the federal city. The new Lincoln administration had offered him command of the Union army being raised to crush the insurrection. Unable to imagine fighting against his native state but still unwilling to take sides against the Union George Washington had forged, Lee rejected the offer but did not yet surrender his commission in the army he had served for more than three decades. With his heart as divided as the riverbanks, he traveled back over the Long Bridge to Arlington House. Once behind the mansion’s massive columns, he entered a hall lit by the old Mount Vernon lantern and lined with paintings, including the earliest portrait of George Washington. Locked among these relics and others—silver, china, and furniture—that had been a part of his life since marrying the daughter of the first president’s adopted son, Lee at last reached his decision. He could see no other path. He would resign from the US Army. Soon he was on to Richmond. En route, crowds swarmed his train at every stop. “Lee, Lee,” they chanted until he appeared on the rear platform with his hat tucked under his elbow. Strands of silver softened the dark hair sweeping over his wide forehead. A neat black mustache firmed up his lips. He stood just under six feet. Then, without uttering a word, he bowed and returned to his seat.

Now, once again, Lee heard his name. The double doors partitioning the chamber from the rotunda opened. An escort guided Lee into the old hall Thomas Jefferson had designed. The delegates stood as Lee entered. More than one noted his “manly bearing.” He walked almost halfway down the aisle and then stopped, as if torn between the Washington statue behind him and the convention president occupying the rostrum ahead. Everyone agreed Lee belonged somewhere along this line—a link between the past and the future. “In the eyes of the world,” one relative said, the wedding thirty years earlier had transformed Lee into “the representative of the family of the founder of American liberty.”

In requesting Lee’s service, President Abraham Lincoln’s emissary had appealed to Lee’s Washington connections. That the Virginia convention planned to do the same would have surprised no one. The delegates considered their choice of a commander in chief to be as momentous as the Continental Congress’s.

Convention president John Janney, a white-haired conservative who had opposed secession before accepting its inevitability, had prepared a formal address suitable to the occasion. He welcomed the new commander in chief of Virginia’s armed forces as the heir to “soldiers and sages of by‑gone days, who have borne your name, and whose blood now flows in your veins.” Two Lees had signed the Declaration of Independence. Another, Lee’s father, had served as one of Washington’s most trusted lieutenants during the Revolution. Washington himself was a blood relative, albeit a third cousin twice removed. Near Washington’s birthplace in Westmoreland County, Virginia, Lee had spent his first years toddling along the Potomac before moving upriver to Alexandria, the town closest to Washington’s Mount Vernon plantation. “When the necessity became apparent of having a leader for our forces,” said Janney, “all hearts and all eyes, by the impulse of an instinct which is a surer guide than reason itself, turned to the old county of Westmoreland.” It was not just the pedigree that persuaded the delegates but also the commensurate talent Lee had shown since his days at West Point. The army’s ranking general had proclaimed Lee “the very best soldier I ever saw in the field.”

Lee, still standing in the aisle, must have thought about Arlington as Janney explained the convention’s expectations. “And now, Virginia having taken her position, as far as the power of this Convention extends, we stand animated by one impulse, governed by one desire and one determination, and that is that she shall be defended; and that no spot of her soil shall be polluted by the foot of an invader.”

The charge was simple, sweeping, and impossible. Lee already knew he could not protect the home he had left. The view he cherished overlooking the nation’s capital would render Arlington indefensible. Federal forces would cross the river, flood up the hillside, and seize the mansion. Unless his wife removed the relics soon, “the Mt. Vernon plate & pictures,” as Lee called them, would be lost. Arlington would never be the same.

Yet whatever reservations Lee harbored about the convention’s judgment, the delegates harbored no doubts about Lee. “Sir,” Janney said toward the end:

we have, by this unanimous vote, expressed our convictions that you are, at this day, among the living citizens of Virginia, “first in war.” We pray to God most fervently that you may so conduct the operations committed to your charge, that it will soon be said of you, that you are “first in peace,” and when that time comes you will have earned the still prouder distinction of being “first in the hearts of your countrymen.”

No one, least of all Lee, could have missed Janney’s allusion. Only one man had ever been “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen”—George Washington. It had been Lee’s father, Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, who coined the phrase in a funeral oration for his old general. So popular had the epitaph become that the words fused the Washington and Lee names long after Harry Lee had drifted into disgrace. As a commentator in Robert E. Lee’s hometown newspaper put it, “The fact that these memorable words, as they were addressed and applied by the distinguished President of the Convention, were the outpourings of his Father’s heart . . . must have been peculiarly touching and solemnizing to the newly appointed generalissimo.” To be first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen would make Robert E. Lee nothing short of George Washington.

What else Harry Lee said has been less remembered. At its climax, his funeral oration summoned Washington’s spirit from the grave. “Methinks I see his august image, and hear falling from his venerable lips these deep sinking words.” In Harry Lee’s telling, Washington’s ghost warned future generations to resist internal divisions.

Thus will you give immortality to that union, which was the constant object of my terrestrial labours; thus will you preserve undisturbed to the latest posterity, the felicity of a people to me most dear, and thus will you supply (if my happiness is now aught to you) the only vacancy in the round of pure bliss high Heaven bestows.

Speaking with one voice, Washington’s ghost and Harry Lee had given future generations of Americans their marching orders. Providence, it seemed, could not have positioned Robert E. Lee any better to answer these pleas for union. But Lee made a different decision. He turned down the Union command. He cast his fortune south of the Potomac, and his legacy has divided Americans ever since.

On one side, southern traditionalists have claimed that the decision transformed Robert E. Lee into the “second coming” of George Washington. Even if the funeral oration suggested otherwise, rebellion against the Union and loyalty to Washington’s memory went hand in hand. Had not Washington led a rebellion against union with the British? The comparisons began as soon as Lee made his choice. Janney prayed for a day when Lee would share the epitaph his father had given Washington. Lee’s own eulogists made it so. An early biographer who had served on Lee’s staff during the war described his chief as “one whom, like Washington, we may designate as ‘first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.’” True, unlike Washington, Lee lost his revolution, but his demeanor in defeat made him all the more noble. “He was,” according to a frequently quoted speech, “Washington without his reward.” After seeing “two splendid equestrian statues” of George Washington and Robert E. Lee, Lee’s nephew ventured, “Riding side by side in calm majesty, they are henceforth contemporaries in all the ages to come.” Indeed, the two horsemen traveled together into the twentieth century. Douglas Southall Freeman, who won the 1935 and 1958 Pulitzer Prizes for biographies of Lee and Washington, concluded that only “modesty” prevented Lee himself “from drawing the very obvious analogy between his situation and that of Washington.”

On the other side of the debate, writers have grumbled that such conclusions have twisted the pro-Union exhortations of the ghost Lee’s father exhumed. How can Lee ride off into history with Washington after fighting to destroy the first president’s “terrestrial labours”? The question confounded many even during Lee’s time. After the Union army seized Arlington in the war’s early days, a British correspondent visiting the home wondered how a rebel general could have lived among Washington’s relics and be the son-in-law of Washington’s adopted child. “Follow the train of thought,” the correspondent wrote, “and you may become as perplexed as I am in reference to the possible status of the pater patriae.” Modern-day debunkers chasing this train of thought have set out to detach Lee’s car from Washington’s by dismissing the links between the two men as “minutiae” cobbled together by Confederate apologists. A recent biographer mocks writers who “envision a mystical bond between” Washington and Lee.

So once more, Lee is trapped in the middle. More than a century and a half after secession forced him to choose sides, he has become a pawn in another conflict between two camps conceding no common ground. Either Lee’s name must be united with Washington’s, or it must be banished from all associations. Something has been lost in this polarization, and that something is the truth. The connections between Washington and Lee are neither mystic nor manufactured. Lee was not the second coming of Washington, but he might have been had he chosen differently. As Washington was the man who would not be king, Lee was the man who would not be Washington. The story that emerges when viewed in this light is more complicated, more tragic, and more illuminating. More complicated because the unresolved question of slavery—the driver of disunion—was among the personal legacies that Lee inherited from Washington. More tragic because the Civil War tore apart the bonds that connected Lee to Washington in wrenching ways that no one could have anticipated. More illuminating because the battle that raged over Washington’s legacy shaped the nation that America has become.

The view from Arlington House today looks very different. The mansion once filled with Washington heirlooms has become the Robert E. Lee Memorial. Where trees once shaded the hillside, the sun now reflects off white tombstones lining the grass. A granite bridge guides the eye across the river to the city of Washington. In the foreground, the marble columns of the Lincoln Memorial, honoring the man who saved Washington’s Union, anchor an axis that extends eastward: first toward the towering Washington Monument and then toward the Capitol dome, clad in iron and crowned by the Statue of Freedom. As the eye follows this axis, the mind wants to believe that harmony governs history. But this is Arlington’s secret: the line connecting Lincoln to Washington and Freedom appears so straight because the house lies not upon it. Lee stares down from the flank, a river away on a path not taken.

Excerpted from “The Man Who Would Not Be Washington: Robert E. Lee’s Civil War and His Decision That Changed American History” by Jonathan Horn. Published by Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster. Copyright 2015 by Jonathan Horn. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.