"Saturday Night Live," amazingly, is celebrating its 40th season on the air, and will mark the occasion with a three-hour live special Sunday night.

Equally amazing, on a more personal level, it’s now three decades since we wrote the first history of the show, "Saturday Night: A Backstage History of Saturday Night Live."

Between 1983 and 1985 we interviewed more than 200 people – everyone from performers and writers to producers, directors, network executives, band members, musical guests, filmmakers, guest hosts, set designers, costume designers, personal assistants, censors and, yes, a drug connection – to tell the inside story of "SNL’s" first 10 years.

Fans today may not realize what a massive cultural phenomenon "SNL" became during that early era. Despite the seismic attention it attracted, however, the show managed – to a degree that would be impossible in the instantaneous tell-all environment of today – to hold onto most of its secrets. Its stars were the subjects of plenty of flattering profiles, but what they revealed remained under their control. As we found out, there was a lot they didn’t talk about, and a lot they would have liked to have kept hidden.

We’ve never written before about the adventures we had writing "Saturday Night." Here are some of our favorite stories.

1. Thanks (sort of), Bob Woodward.

We had two key advantages going for us when we started our research. The first and by far the most important was Lorne Michaels’ blessing. It’s likely that few involved with "Saturday Night Live" would have talked to us had they not been told by Lorne, then as now the undisputed Godfather of "SNL," that it was OK to cooperate.

Our second advantage was timing. By the time we showed up many people who had worked on the show were ready to tell stories they’d been keeping to themselves for years. Lorne’s permission opened the floodgates. We were told repeatedly that talking to us was like talking to a psychiatrist.

What we didn’t realize until later was that "SNL’s" veterans were also happy to talk to us because they were annoyed with Bob Woodward.

When we started our interviews, Woodward was completing his research for the book that would become "Wired," his biography of John Belushi. Several people told us that the "SNL" troops were initially thrilled that one of the reporters who’d brought down Nixon would turn his attention to them. Soon, though, it became obvious that Woodward’s focus on Belushi meant he wasn’t especially interested in "Saturday Night Live."

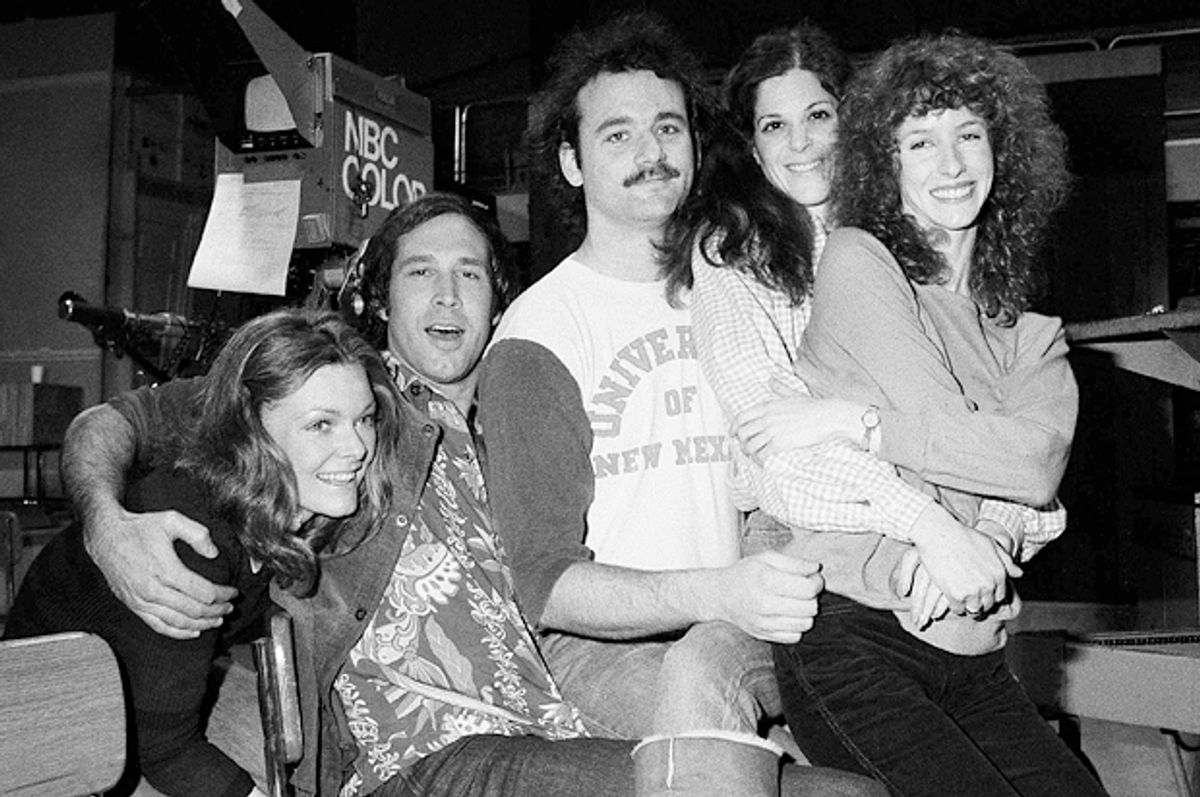

This touched an old wound. Starting with Chevy Chase’s breakout during the show’s first season, everyone on "SNL" hated the tendency of the press to single out one or two cast members for attention, ignoring everyone else. That’s not what we had in mind. We were writing a biography of the show. Finally, someone was going to tell the whole story. That helped give us an opening we were able to widen over time.

We’d almost finished our research when "Wired" came out, which was fortunate. Everyone involved with "SNL" was repulsed by Woodward’s book, and some reconsidered the wisdom of trusting any reporter. A few stopped returning our phone calls.

2. “Hold for Dan Aykroyd.”

Although timing and Lorne’s approval worked in our favor with almost everyone involved with the show, most members of the original cast were exceptions. All of them were still recovering from years of living with relentless media scrutiny, and almost all were still dealing with emotional issues their stardom had created with Lorne and others within "SNL."

Among the cast members we most wanted to talk to was Dan Aykroyd, whom we considered (and still consider) one of the great comic geniuses in "SNL" history. Writers and occasional performers Al Franken and Tom Davis, whom we interviewed many times, were especially close to Danny and worked hard to convince him to talk to us. Finally he agreed to a phone interview.

He was on a movie shoot, we were told, but would take our call in his trailer. The interview was set for a Monday, and we spent the entire weekend prepping. At the designated hour we placed the call, but the woman who answered said that Danny was busy; we should call back in an hour. We did. Same answer. We called again. Same answer. Finally our phone rang.

“Hold for Dan Aykroyd, please.”

“Gentlemen,” he said. He didn’t give us a chance to return his greeting. Instead he immediately let loose a nonstop, two-minute verbal assault, a barrage of staccato invective that sounded to our ears like machine-gun fire. The gist of it was that we had a lot of nerve thinking that we could write a history of a show we were never a part of; who did we think we were? Specific comments we remember include a sneering dismissal of our business card (it simply read “The SNL Book” with our names and phone numbers) and an accusation that we were no better than “pornographers.”

Insulted and frustrated, we were waiting for a chance to respond, but we didn’t get one.

“That’s it, gentlemen. I’m done,” Danny said, and hung up.

Three years later Jeff ran into Danny at an end-of-the-season "SNL" party, introduced himself and braced for another onslaught. It didn’t come. Danny’s opinion of our project had changed dramatically for the better. The word “pornographers” wasn’t mentioned.

3. Close encounter.

Another original cast member we especially wanted to talk to, for very different reasons, was Garrett Morris. Fans of the show today may not recognize the name: Garrett was the only black member of the Not Ready for Prime Time Players, and his impact on the show was minimal.

There were four basic reasons for that. One, he wasn’t a particularly talented sketch comedy performer. Two, he didn’t become a forceful advocate for himself with the writers or with Lorne, a requirement for success in the show’s fiercely competitive backstage environment. Three, the writers, who considered themselves enlightened progressives, seemed incapable of writing material for Garrett that wasn’t embarrassing in some way — at times it seemed they were almost intentionally setting out to humiliate him. Many of his parts required that he appear in drag. Four, over time, he became increasingly compromised by drug use.

Because of these problems, we thought it was important to hear Garrett’s side of the story. His representatives, however, instantly and emphatically declined our repeated requests for an interview. That seemed to be that, until a bizarre encounter in a locker room in Los Angeles.

We were based in New York, but about midway through our reporting we spent seven weeks doing interviews in Hollywood. We stayed at the Oakwood apartments in Toluca Lake, a well-known stopover for B- and C-level showbiz types having extended business in town. Jeff was in the habit of starting his day with a run, followed by a shower in the complex’s locker room. It was there one morning that he almost literally ran into Garrett Morris. A naked Garrett Morris.

Simultaneously catching his breath and regaining his composure, Jeff managed to explain that he was one of the reporters who had been trying to reach him for an interview for a book about "SNL."

Garrett interrupted. “I am not talking to you guys.”

Jeff persisted. “Garrett, if you could give me one minute…”

“No,” he repeated, almost shouting. “I am not talking. That’s it.”

Just as abruptly he turned and walked away.

Jeff didn’t follow, but as he left the locker room a few minutes later he spotted Garrett (by this time wearing a bathing suit) sitting next to a woman in the hot tub. Jeff gave it one more try.

“Garrett,” he said.

“No!” came the immediate, high-pitched response, this time definitely shouted. “Get away from me.”

Jeff did.

4. He’s Chevy Chase (and you’re not).

One of the stars we talked to at length during our time in Los Angeles – three long interviews – was Chevy Chase, who welcomed us into his lovely home in Pacific Palisades. Something you learn as a reporter, or should learn, is that some people will become your most generous sources because they have the most to gain from steering the story in a certain direction — and away from other, less desirable directions. This may have been the case with Chevy.

To be sure, Chevy told us a lot of good stories. We appreciated his time, and we respected his enormous contributions to "SNL’s" early success. Talking to others, however, it became clear that the majority of his former colleagues considered him an obnoxious egomaniac who betrayed the show in general and Lorne (his best friend at the time) in particular. That’s what we reported, which didn’t please Chevy. After the book came out he told Playboy in an interview that he’d like to meet us in a dark alley while armed with a pair of pruning shears.

5. A little help from our friends.

One of the things that surprised us in the course of our research was how much we enjoyed talking to the executives at NBC. We interviewed a lot of them, and with few exceptions they turned out to be surprisingly forthcoming. Some were even colorful. Network budget chief Don Carswell, for example, had a glint in his eye, a taste for irony and a 6-foot-high poster on his wall of a charging, sword-wielding Scottish warrior. The caption beneath read “The Spirit of Compromise.”

When "SNL" first went on the air, the reaction of NBC’s top executives was almost uniformly negative. They were offended not only by the show’s humor — here again, it’s hard to remember at this distance how aggressively "SNL" challenged TV conventions — but also by the behavior of its staff, who not only worked but almost lived within NBC headquarters at 30 Rockefeller Center. Coupled with the show’s early struggles in the ratings (contrary to popular belief, "SNL" was not an immediate hit), the animosity toward the show in NBC’s executive suites made its cancellation a distinct possibility.

Eventually those feelings gave way to pride that their network had given birth to such a groundbreaking show, which is why so many executives were willing to talk to us. Some reservations remained, however. Chief among them was the fact that everyone at NBC, from the pages to the chairman of the board, was well aware that drugs were a daily fact of life on "SNL," both in the show’s offices on 30 Rock’s 17th floor and in the facilities surrounding Studio 8H.

To their credit, none of the executives we interviewed denied knowing what was going on, including the head of public relations at the time, M.S. (Bud) Rukeyser Jr. Asked how it felt to read interviews where members of the cast talked about using drugs, as several did, Rukeyser said, “It’s a bitch.”

NBC executives were equally forthcoming about their tolerance of the drug humor "SNL" put on the air, which regularly conveyed a familiarity with and approval of illegal substances. These jokes (many of which featured John Belushi, whose devotion to intoxicants was an ongoing comedic theme) were a clear violation of NBC’s Standards and Practices policy.

This was in the days before the children of the counterculture had children of their own, and it was assumed that "SNL’s permissive attitudes about getting high were shared by its audience. Standards and Practices chief Herminio Traviesas told us he was uncomfortable with the show’s drug humor, “but I didn’t think we were changing viewers’ habits.”

Similarly, NBC chairman Julian Goodman said it bothered him that "SNL" “always managed to slip in something that gave you the impression [that using drugs] was OK.” When we asked whether NBC couldn’t have simply insisted that no more drug jokes be “slipped in,” we were startled by his answer.

“You could say it,” Goodman said, “but you could not say it and keep the show.”

6. Shocked!

What we reported in our book took a lot of people by surprise, including journalists. An especially agitated article appeared in the Washington Post. It was written by Tom Shales, then the Post’s TV critic, later the co-author of a best-selling oral history of "SNL."

Shales was a prestigious writer for one of the nation’s most prestigious papers, and his early, enthusiastic support of the show helped stave off its cancellation. His acumen as a critic, however, did not necessarily mean he was aware of what had been going on behind the scenes.

“You may not have to be crazy to work in television,” he wrote, “but after a few weeks, you will be.

Additional proof of this, as if any were needed, comes in 'Saturday Night: A Backstage History of Saturday Night Live,' a fascinating and lurid new book about the landmark comedy program’s 10 tumultuous years on the air.

A more disagreeable, egomaniacal, selfish and dissipated crowd you wouldn’t want to meet than the changing casts and staffs of the show, at least as authors Doug Hill and Jeff Weingrad portray them. It appears they all took turns behaving like swine.”

We had actually tried to temper just this sort of harsh judgment by including in our foreword a request that readers keep in mind that the accounts they were about to read concerned people who had been “operating under extreme pressure,” adding, “In particular, the effects on the psyche of major stardom, though a part of popular legend, are underestimated.”

Shales disregarded this suggestion, going on to recount some of our more sensational revelations — John Belushi’s misogynist rants, a backstage fist fight between Bill Murray and Chevy Chase, Gilda Radner’s bulimia, the widespread use of drugs, etc. “Everybody hated everybody else,” he wrote, adding, “Drugs were everywhere.”

We can’t argue with his comment about the drugs, but the part about everybody hating everybody else was, we think, somewhat overstated.

Shares