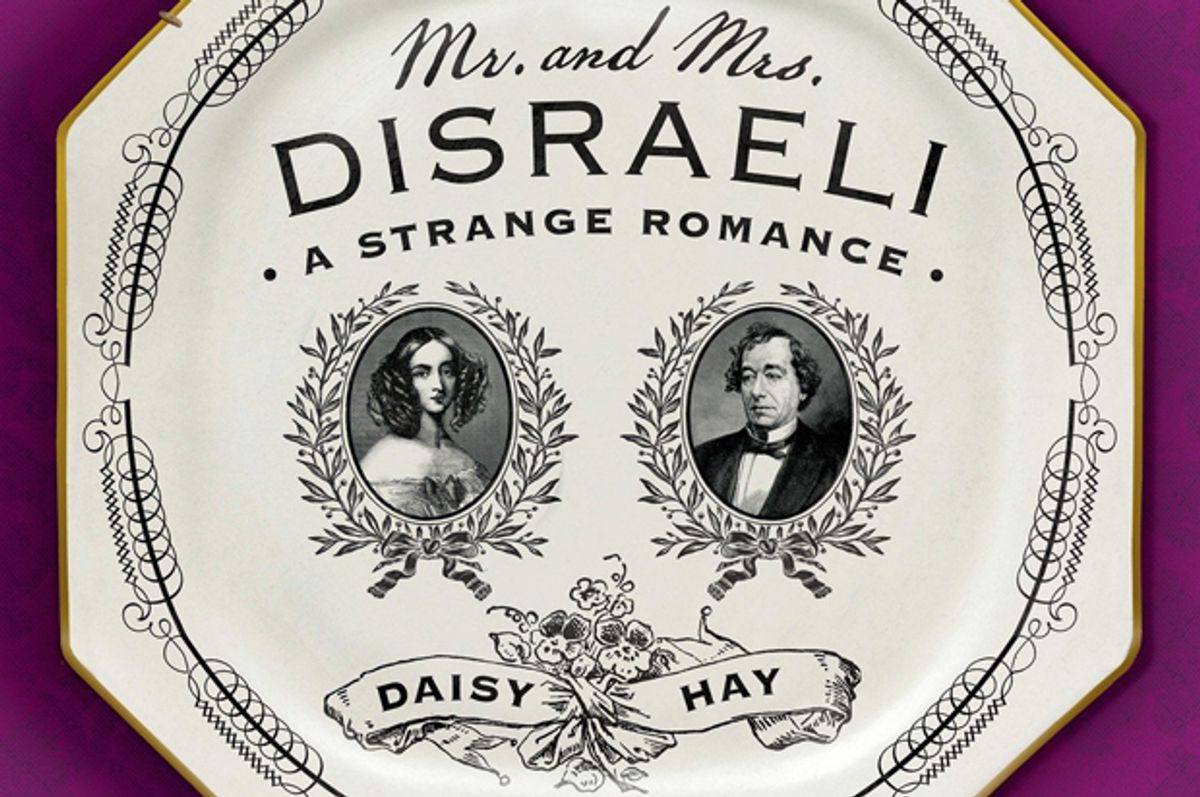

It's not exactly a love story, "Mr. And Mrs. Disraeli: A Strange Romance," the new dual biography by British writer Daisy Hay, or at least not in any conventional sense of the word. He was one of history's most talented politicians, a leader of the Conservative Party in England for 30 years, two-time prime minister, bestselling novelist, favorite of Queen Victoria and eventually the Earl of Beaconsfield, despite having been born a Jew (converted, but they certainly never let him forget it) of modest means. She was a sailor's daughter, raised on a farm, clever but flighty in her youth, a pretty, provincial flirt who married a wealthy merchant. Her first husband died in 1838. A year later, in possession of a London townhouse and a handsome annual income, she wed Disraeli -- or Dizzy, as she and an entire nation would come to call him -- an ambitious novice politician 12 years her junior.

Accounts of Benjamin Disraeli's career as a statesman can and have filled numerous hefty volumes; for better and worse, he was a key architect of the British empire. "That old Jew, that is the Man," Bismarck marveled after wrangling with him at the 1878 Congress of Berlin. But Hay's is a relatively slim book and deals almost exclusively with the Disraeli marriage, a remarkable fusion of pragmatism, fiction, propriety, strategy and, eventually yes, deep and abiding love. Mary Anne Disraeli's relationship to her husband could single-handedly stand as proof of the old saw that every marriage harbors a mystery.

Political marriages, of course, can be some of the strangest romances around. They fascinate us because they illustrate, writ large, the way that every marriage is part public performance and part private drama, with the line between the two anything but bright. It might be difficult for any American to read "Mr. And Mrs. Disraeli" without thinking of such famous contemporary (or near contemporary) couples as John and Martha Mitchell, Ronald and Nancy Reagan or Bill and Hillary Clinton. In the case of that last pairing, history has wrought an enormous transformation since the Disraelis' day, allowing the wife to aspire to the same supreme position her husband once commanded. But certain enigmas are eternal: Which partner has the upper hand? How sincere are their feelings for each other? Would their marriage even (still) exist if not for political necessity?

A successful parliamentary career in 19th-century Britain required two things above all: money, since getting the most votes in a borough typically came down to bribery in one form or another, and social standing, which allowed a member of Parliament to parlay his connections into plum appointments and other forms of influence. Mary Anne Lewis first met Benjamin Disraeli when he ran as second to her husband, an undistinguished MP. She recognized his gifts, intellectual and oratorial, from the start, and, an excellent campaigner, she had acquired a taste for politics herself. With her husband's death, Mary Anne acquired money as well, although not as much as it at first appeared. Disraeli, however, was chronically in debt due to his early political forays. Parliamentary privilege protected MPs from the legal consequences of overdue loans, but since in 1838 the government seemed about to dissolve, he found himself in serious peril: Either pay off his creditors, get reelected (requiring even more cash he didn't have), or marry for money. The alternative was debtor's prison or exile on the Continent.

Some of the most fascinating passages in "Mr. and Mrs. Disraeli" recount the couple's courtship during this time of crisis. (Hay's primary sources are their letters; Mary Anne's have been comparatively untapped by historians.). She was 47 and he was a 35-year-old dandy who emulated the late poet Lord Byron so much that Byron's servant was hired to work in the Disraeli household and treated with extraordinary deference. Both acknowledged their potential marriage as a union of convenience, but, as Hay notes, at the same time "it mattered to them both that they should be, and appear to be, swept up in a grand romance." So they wrote and behaved toward each other like real lovers. Disraeli had already written a few novels in which the typical Victorian marriage plot was used as a support for his political ideas. In that respect, his marriage would be rather like one of his books.

But somewhere along the way the two started sleeping together and the literary performance of passion became something a bit more -- but how much more? -- than a mere performance. Mary Anne would entertain other suitors, often somewhat disreputable characters, and Disraeli would write her angry letters, demanding that she set a date, to which she responded that since he only wanted to marry her for her money, she saw no reason to rush, or even to marry at all. In a remarkable letter that precipitated their wedding, Disraeli wrote to say that despite the mercenary motives that first prompted him to propose, he had since realized that she was "amiable, tender and yet acute and gifted with no ordinary mind." Besides, she didn't have that much money, and if she was just going to toy with his feelings, he was better off without her. "He was angry," Hay writes, with her own acute understanding of the intricacies of human emotion, "and having half convinced himself of the veracity of his feelings, he was hurt by the suggestion that his passion was somehow inauthentic."

They patched it up and married in 1839. Mary Anne was not the ideal choice for a man destined to scale the heights. Many of the well-born and fashionable people the Disraelis needed to rub shoulders with found her conversation vulgar and her fashion sense garish. (Mary Anne liked to spangle her gowns with jewels and feathers, and she frequently wore colors more appropriate to a much younger woman.) She had a chattering, free-associative manner of speaking that led her to say whatever came into her head. Some of it, such as references to her husband's appearance in the bathtub, shocked the more straitlaced members of Victorian high society, while others found her an amusing and fundamentally warm-hearted character. Tellingly, prolonged exposure to Mary Anne tended to lead to greater affection for her. Her husband was not alone in coming to, in Hay's words, "appreciate the qualities others loved in her: spontaneity, a merry disposition, sound judgement and a conversational style as surprising as it was quick."

Mary Anne also doted on her husband, and won over such initial critics as Queen Victoria with her devotion. Disraeli rose to power in an age when disgust at the excesses of the decadent Regency aristocracy had led to the enshrinement of bourgeoise family values. Disraeli himself, both aware of this and caught up in the fictional romance he'd conjured, spoke of Mary Anne as "the perfect wife" and lavished courtly gestures on her. He was also profoundly appreciative of the way she ran their London household and could barely manage the servants during her rare absences. Nevertheless, in the early years of their marriage, the rising political star's uxoriousness toward this (to quote one satirical publication) "middle-aged, comfortable, matronly looking dame" struck friends as peculiar and outsiders as hilarious.

In time, however, the evident sincerity of the couple carried the day. "It is certainly a very remarkable alliance," one observer wrote. "That her heart, however, is as kind as her taste is queer, everyone admits; and she has splendid pluck and illimitable faith in Dizzy."

The Disraelis' relationship had its few rocky patches. She was jealous of his sister, with whom he carried on a secret, confidence-sharing correspondence, and his eye did wander on occasion. (Throughout his life, Disraeli was drawn to older women and younger men, although speculation about his interest in the latter remains just that.) As the years went by, the more dedicated the Disraelis became to each other and the more that dedication was honored by those around them. In one celebrated incident, Mary Anne accompanied an ailing Disraeli in his carriage on the way to make an important speech. Her hand was badly hurt when the carriage door slammed on it, but she kept the injury a secret until afterwards to avoid distracting him. When the Earl of Derby, the titular party leader, upset Mary Anne by "chaffing" her at a dinner party, Disraeli left the earl's estate the following morning and refused all invitations to visit it again.

Of course, Disraeli's growing power made it increasingly advantageous to accept his choice of spouse, but it was not just the political classes that took to Mary Anne; she became a popular figure as well. Who can say if the public came to love Mrs. Disraeli because the leader they loved loved her too or if his fidelity was one of the qualities that made them adore him in the first place? When, in 1867, Mary Anne first suffered the illness (probably uterine cancer) that would eventually kill her, she lay near death for several days. The newspapers published regular bulletins on her condition, and kings, queens, former servants and complete strangers wrote her get-well letters. During that period, Disraeli himself endured an attack of lumbago and could no longer climb the stairs to check on her. The couple, 63 and 75, sent notes back and forth between their rooms via the servants. Their house, Disraeli wrote to Mary Anne, "has become a hospital, but a hospital with you is worth a palace with anybody else."

Is it even possible to separate the playacting from the reality in this adorable "personal story" of true love discovered in life's third act? Hay points out that Disraeli was one of the first politicians to recognize the power of turning his own life into a symbolic narrative in order to appeal to a whole new population of middle-class voters. The "shameful" facts once thrown in his face -- his Jewish heritage, his unillustrious upbringing as a scholar's son -- over time became points in his favor, and even in favor of the novels he wrote during his youth. "Like the author himself," the Daily News wrote of these books, "they have made their own way, and conquered their own place. Like him, they have compelled even opponents to listen." It was the same with Mary Anne; he made the world appreciate her. "We have been married 33 years and she has never given me a dull moment," he told a friend when Mary Anne lay, at last, on her deathbed. Now that is a statement, devoid of Victorian sentiment, that has the ring of unvarnished truth.

Shares