You are about to read a story based on the best interview Brian Wilson has ever had. I know it’s the best, because I asked him. He sat back on his leather couch, locked me with those ocean-blue eyes that have seen so much and said, “It is.”

I’m not bragging. Just stating a fact. I mean, there’re probably a lot of interviews Wilson’s forgotten. Maybe even great ones. The man has spoken with countless magazines, newspapers, radio programs, TV shows, you name it. He’s had to talk about himself and his music since the Beach Boys’ debut declaration of a life aquatic, the release of the single “Surfin’.” That was in 1962.

Now he’s got to get back on that promo horse and ride, thanks to the release of his 11th solo album, “No Pier Pressure,” and the Bill Pohlad-directed biopic “Love & Mercy.” It’s a saga so great, so awash in mental turmoil, drug abuse, redemption and unequaled musical brilliance that it took two actors, Paul Dano and John Cusack, to play Wilson.

Still, this interview stuff, it’s not his favorite way to pass the time. Never has been. Tales are legion of journalists prepared with probing, deeply researched questions who find themselves confronted with answers consisting of “Yeah,” “No” or “I don’t know” spit back at them like ack-ack fire.

He’s also been known to get up, extend a hand and blurt out “Thanks!” well before the allotted time is up. And sometimes he just gets tired and shuts down.

None of this, however, is due to a bad attitude. He’s not trying to be rude or insulting, Wilson is simply an unfiltered guy, painfully honest, easily bored, seemingly without ego or irony or any real sense of his celebrity. Music, family, a melted cheese sandwich…these are things that seem more important to him than the chores attendant with tending to fame.

And his struggles with mental health issues are very, very real. He hears voices. Voices saying far worse things than any journalist.

*****

“So this is gonna take like, 10 minutes, right?”

That’s the opening salvo from Wilson. He’s just lumbered into his upstairs music room where I’ve been waiting, a comfortable space with a grand piano, tall windows and a table choked with awards. There’s the Beach Boys’ sole Grammy, for 2012’s Best Historical Album, “The Smile Sessions.” It’s kept well dusted. There are still-crated gold records on the floor leaning against the wall, stacked next to a portrait of brother Carl Wilson, sun setting on the sea behind his head, who died of cancer in 1998.

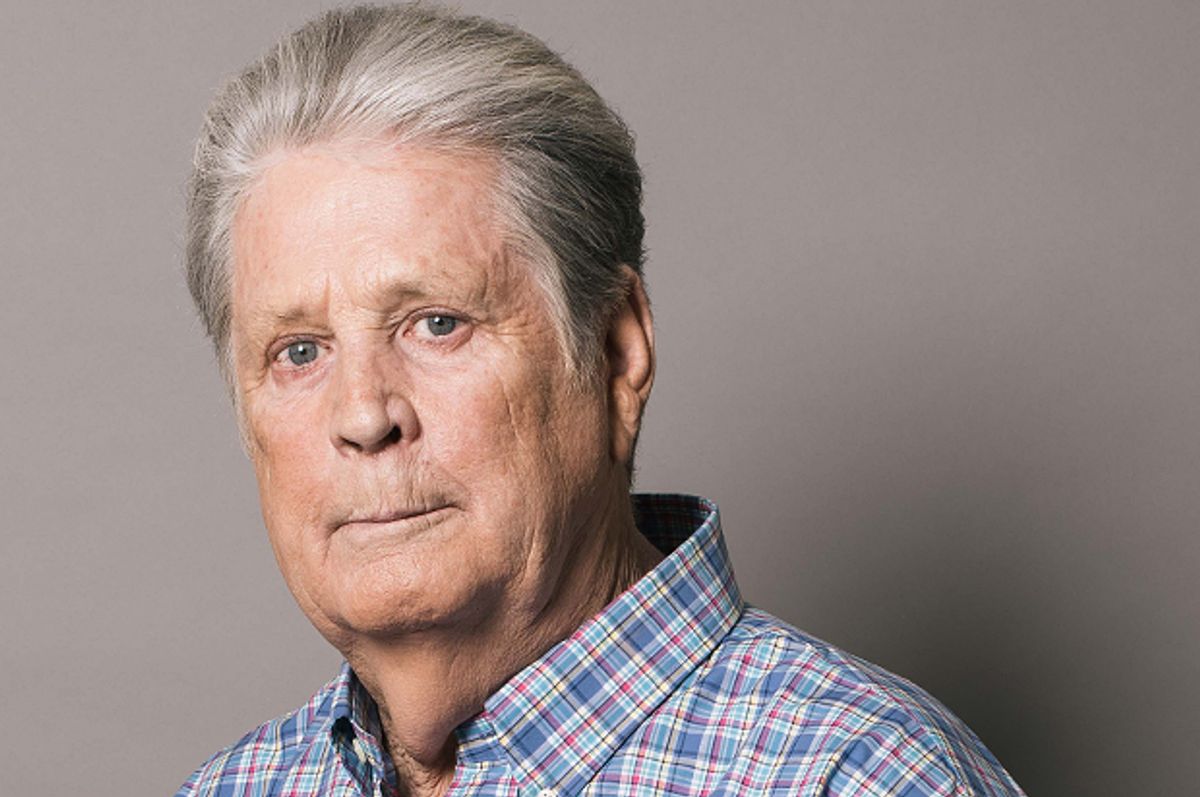

Brian’s a big guy. Former high school jock. At 72, he’s put on a few pounds, has had some back issues, but he still has the firm handshake of a man born in a time when firm handshakes mattered. He eases into a deep leather chair and looks at me with his trademark, penetrating Wilson Vision as he slowly, silently sinks lower, awaiting an answer.

“Yeah, ten minutes. Or longer. Maybe longer,” I say. “What have you got to do today?”

“Gonna get a haircut.”

Wilson has an impressive head of full, graying hair, swept back. I, on the other hand, am bald.

“I wish I had your hair. Mine started flying out when I was 35.”

He pauses. “What happened?”

This, I will come to learn, is a prime example of a Brian response. Nothing is taken for granted. The obvious is nebulous. That question hangs there for a few seconds, and then Mrs. Wilson comes in. This is a special occasion. To plug the film—in which her character, played by Elizabeth Banks, figures prominently—Melinda has consented to join the interview with her husband.

They met 29 years ago, were married in 1995. They have five children and 12 dogs. She rarely talks to the press and has no truck with the spotlight. I’m told the only person to speak to them together was Larry King, some ten years ago.

They cozy up on a couch. He places his large, New Balance-clad feet on the coffee table. She hands him a throw pillow which he rests on his stomach. Okay. The Wilsons emit the vibe of a content, comfortable, long-time couple. She is a gracious woman and her strong, quiet presence puts Brian at ease, a bit.

As their story unfolds in “Love & Mercy,” Melinda Ledbetter was a salesperson at Martin Cadillac in West Los Angeles in 1986 when Dr. Eugene Landy (portrayed with bug-eyed, Napoleonic ferocity by Paul Giamatti) entered her life. He was car shopping. The late Landy was the controversial psychotherapist hired initially by Wilson’s first wife in 1976 to combat his drug abuse and general downward spiral. Landy ultimately took control of virtually every aspect of his patient’s existence until he was barred from contact by court order in 1992.

How would today’s Brian advise his younger self on the Landy interaction? “I would say, no thank you,” offers Wilson without hesitation. “Don’t need to go into a program.”

“That’s really putting it nicely, honey,” counters his wife sweetly. “I would have used some bad words, probably. Some really bad words.”

She’s not kidding. Landy was “a fucking asshole,” says Melinda, reserving her only f-bomb of the conversation for the doctor. “I think he was crazy. He was a manipulator… Brian was kind of like a puppet, so he would parade him out and if he needed to give him an upper or a downer or whatever it was, that’s what he did.”

“Landy was kinda strict,” ventures Brian, who apparently doesn’t have a mean or resentful bone in his body. “He medicated me, he manipulated me, you know?”

While Landy “ran me around the block for a couple weeks, then he announced he was going to go buy a Maserati,” sniffs the former Caddy power seller, she and the mysterious man Landy kept in tow—she had no idea who Wilson was—came together over an ’86 brown Seville.

Brian lights up at the memory. “Right! Right! Yeah!”

“It was the ugliest car we had,” Melinda laughs.

“I liked it though, I chose that one cause I liked it. That one’s for me.”

“My take is, he liked it because it was the first one he saw and he didn’t have to go upstairs and traipse through 300 cars. That’s how little a car really meant to you at the time.”

“A car’s okay for me, you know? A car’s all right to drive. Not to look at, to get in it and drive it.”

And to write songs about, presumably.

“Right, well I wrote a few car songs, yeah.”

*****

Here’s something from Brian’s life that’s not in the film. In September 1960, Wilson enrolled in El Camino College, a two-year institution near his boyhood home in Hawthorne whose attendees have reportedly included Chet Baker, Suge Knight, Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme, Frank Zappa and Bo Derek.

Brian did not major in music.

“I just wanted to be a psychologist, you know? I liked the idea of wanting to be a psychologist,” he says.

“Did you ever really want to be one though?” asks Melinda, turning to look at him on the couch.

“Yeah. I wanted to be a psychologist, yeah.”

“Wow. Why?”

“I don’t know. It’s way, way too many years ago.”

“If I give you a million dollars, can you tell us why?”

“No. Fifty-four years ago? I’m not going to be able to remember nothing.”

She turns to me. Half shrugs. “Usually that bribe works. I never pay him off though.”

How the life of Dr. Wilson might have played out is another story, but Brian the musician has dealt with issues of the mind for most of his life, a dark, wrenching part of his story that is a key theme of "Love & Mercy."

“I had no idea how much until the first time I saw it and it was like, I didn’t know what to say,” Melinda says. “Brian wasn’t with me cause I wanted to be the buffer in case it was just, oh my God. And it was like, oh my God.”

Brian has seen it twice, and while he feels the filmmakers “did a great, great job…it was tough to watch, it really was.”

The film contains vivid scenes of Wilson suffering from what Melinda says is “schizoaffective disorder, which is a manic depressive with auditory hallucinations.”

“I have voices in my head,” clarifies Brian. “Mostly it’s derogatory. Some of it’s cheerful. Most of it isn’t.”

It’s a condition that’s proven difficult for people outside of his inner circle to comprehend.

“They totally don’t,” Melinda says, “and it pisses me off. He’ll be doing a concert, and I can tell. I can see the look in his eyes, his face, I can tell when [the voices] are bothering him, and yet he just champions through it. He’s to be commended for that, in my opinion, and I hate it when people say he’s up there like a zombie. Well, they would be too if they were dealing with what he deals with. It’s something that he’s going to have forever and it’s amazing that he gets through life as well as he does.”

The other side of Wilson’s mental anguish is, of course, the brilliant, visionary music he’s created. Some of the movie’s highlights are the meticulous recreations of the master at his best, working in the studio with the Beach Boys and the crack session musicians known as the Wrecking Crew that you’ve heard backing the band on virtually every ‘60’s Wilson hit.

“They were pretty much verbatim as to how I was in the studio,” he says of those scenes. “In the movie the Wrecking Crew were all actors, but they were good musicians. Real musicians. Darian put that together.”

*****

Darian Sahanaja is the man responsible for those verbatim scenes. Since 1999, he’s been singing and playing keyboards in Wilson’s band, and was the consulting musical supervisor on the film. He’s a firm believer in God being in the details, and, as Brian says, “God is music.” Sahanaja pushed for and hand-picked accomplished players to portray the Wrecking Crew, and he provided sheet music transcribed from the original studio recordings. In other words, what you hear and see in those scenes is as close as you’re going to get to witnessing the real thing.

“It was really funny cause I remember working with the prop guys and they were like, ‘You want the amps to work? You want ’em functional?’” laughs Sahanaja.

Initially he was skeptical about the project. “I really didn’t know what the direction of the film was going to be. I’ve seen Beach Boys related biopics made before and they wouldn’t be something that I would want my name attached to,” he said. That changed after meeting with director Pohlad.

“First thing he said to me was, I’m not interested in making your typical biopic, and I was like, ‘Oh great!’ The last cut I saw was very satisfying to the point where I actually teared up.

“What I loved about the movie was the film making matched the artist,” continues Sahanaja. “Brian’s an enigma, and the film making felt enigmatic, so there’s lots of moments of beauty and sadness which to me is a big part of Brian’s music. Joy and tragedy, you know?”

It’s music he’s well familiar with. Growing up in the Los Angeles suburb of Eagle Rock, Sahanaja, 52, fell in love with Wilson’s music when he was 12.

“In a period when it was way cooler to be listening to Led Zeppelin and the Stones and Aerosmith and all those groups, I actually took regular beatings from neighborhood boys because I loved the Beach Boys,” he reveals.

“Sometimes it freaks me out when I’m onstage with Brian and I think, ‘Wow, his music really shaped my personality in that way,’ but that’s how powerful that music was. I would always look forward to sitting down in front of that stereo and listening to 'The Warmth of the Sun'.”

*****

Back in the music room, Brian’s been talking a lot longer than ten minutes. He’s closing his eyes now and again, but he’s been focused, sincere, laughed a few times, been oddly charming.

For all his quirks, he’s a survivor. Of an abusive father, of mental illness, of family tragedy and show business. He’s tried. God knows he’s tried.

“Yeah, I think I made the right moves,” says Wilson.

“He’s the best person I know,” says his wife.

“Like when I made records I think I made the right, appropriate kind of records when we made them, in their time.”

Now he’s ready to move on — literally.

“I go to a park and take walks for a half hour every day,” he says. Then, with a dry laugh: “I’m trying to stay young.”

Does he get recognized?

“Yeah, a lot. Yeah. People say, ‘Hi Brian, how are you?’ and I don’t know who in the hell-heck they are, I don’t know. I think I’m gonna go take an exercise right now.”

He shakes hands and says, “Thank you very much.”

Yet he stays seated. Extends his hand again.

“Wanna help me get up?”

I do, and he’s gone.

Shares