Some were mysteriously scooped up for crimes they had supposedly committed. Others lived in the ruins of post-Katrina New Orleans. Still others – like the teenager in East Harlem who woke up to find FBI agents with loaded guns in her family’s apartment — saw parents or spouses dragged away with little explanation. There are confounding and engaging stories from all over the world in the Voice of Witness oral-history series McSweeney’s puts out, all of which try to give the rest of us a fuller and more human sense of what’s going on in the world. “To read a Voice of Witness book,” short-story master George Saunders says, “is to feel one’s habitual sense of disconnection begin to fall away.”

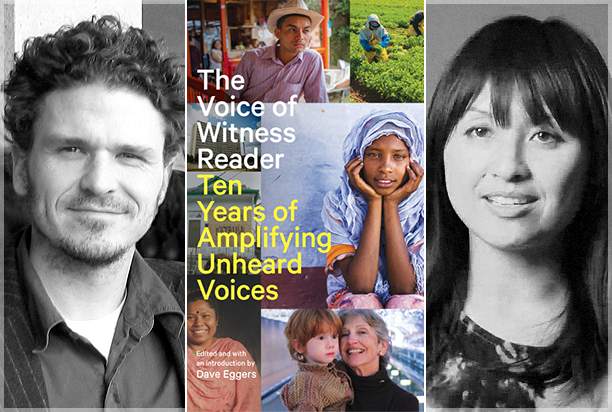

San Francisco-based McSweeney’s has just put out a selection of its previous books – which include “Surviving Justice” and “High Rise Stories” — called “The Voice of Witness Reader.” We spoke to executive editor Mimi Lok and Dave Eggers, McSweeney’s founder and editor of the new volume.

For people who don’t know, what is the Voice of Witness project about? What does it aim to do? And how does this collection fit into the larger mission?

Lok: Voice of Witness is a nonprofit based in San Francisco. We’ve been going for about six years as a nonprofit. The mission, because every nonprofit has to have a mission, is to foster a more empathy-based, more nuanced understanding of human rights crises. Basically, we want to change the way people think about human rights crises. We do this through providing a platform for people who have been most impacted by some of the most crucial human rights crises of our time to have a voice and to share their stories and experiences. It’s often left out of the mainstream narrative around these issues. We also do this through our education program. The books themselves have covered a wide range of issues, everything from wrongful conviction to undocumented immigration and Chicago Public Housing. And internationally we’ve interviewed people from Burma, Sudan, Colombia, Zimbabwe and Palestine.

The book series started 10 years ago, with the first book being “Surviving Justice: America’s Wrongfully Convicted and Exonerated.” “The Voice of Witness Reader” is basically a greatest hits of the last 10 years of the book series. But it also features some of the most powerful narratives, these edited oral histories of these people from the last 10 years. Each book is represented and we had the hardest time choosing stories from hundreds in the series. The selection that is in the Reader is people whose narratives are somewhat — in some cases just one narrative from a book, in some cases there are a couple of shorter ones — but we wanted to include stories that reflect experiences and issues that are still ongoing, stories that are emblematic of an issue.

A good example is Beverly Monroe and Chris Ochoa. And Chris Ochoa is not an unusual person, profile-wise. Prison, wrongfully convicted, a man of color. With Beverly Monroe, she is this soft-spoken woman from the South with a degree in organic chemistry, the epitome of southern gentility, and suddenly she gets wrongfully accused of the murder of her longtime partner. So we wanted to also include these more unusual stories to say that this shit can happen to anyone.

Most of the narrators in this book are people who we get updates from. We wanted to share with readers where are they now and what have they gone on to do. In some cases they are simply just living, struggling. Or maybe their cases have improved. In cases like Beverly Monroe or Ashley Jacobson or Theresa Martinez, from our women’s prisons, they have become quite powerful and active spokespeople for either justice reform or reproductive rights in prison. There is a range.

Dave, you say in your introduction, “A human is more than his or her trauma.” Tell me what you mean by that, and why that idea is important.

Eggers: Well, I think that that notion or that idea maybe was first formed when we did the interviews for “Surviving Justice.” We heard again and again from the narrators that they felt even when they were written about in media articles and newspapers that it was so brief sometimes and so focused on what had happened to them, that moment when they were arrested or jailed, and there wasn’t much follow-up in terms of their life before or after.

They exist as an anecdote in our minds.

Eggers: They exist as an anecdote or a statistic. I noticed it again when reading what little literature or information there was out there about women and children who have been abducted during the Sudanese Civil War. There was so little out there, and there was maybe a name here or there in a few sentences and a statistic or some estimates. There wasn’t much that allowed those people to seem fully human. That guided our approach to oral history, which is really trying to expand the scope of what a narrator was allowed to tell us about their lives and give them more space and more room and start at the start so that we could better know them, empathize with them, walk many miles in their shoes, and could know how they arrived at this place where their rights were compromised, and what happened afterwards. With “Surviving Justice,” it was one of the primary goals to find out what had happened and what the lives were like for these narrators after they had been freed, after exoneration, after freedom. Most of the time, their lives were still exceedingly difficult with very few or no services for exonerees. That story became an essential part of it, not just to say, “Here’s when they were convicted. Here’s when they were freed,” and to end it there, which was the tradition: to end when they got out of prison. To keep going for the years afterwards and to give us the full consequences of that.

Right, so we can’t really understand this stuff if we just see it as a snapshot.

Eggers: Well, I think that snapshots are sometimes part of it. The media has no choice but to sometimes give us a snapshot. It’s a rough draft of history, newspapers and media and the news where you have to react on a day-to-day basis. But I think that that’s the first draft, and then, ideally, if you wanted to know about one of the issues talked about in one of the Voice of Witness books, I think oral history is just a really central part of that issue, whether it’s public housing, whether it’s the situation in Colombia, in Zimbabwe, in South Sudan, or understanding an issue like the rights of workers in the global economy. What we find again and again is people that feel like they, even people who work for NGOs and that field, find that they learn new things. Because even if you do have clients, and I have a lot of friends who are asylum lawyers, for example, there’s a certain limit for how well you get to know a client and how well you get to know people who are in the sphere of your interest or influence. Oral history provides this long, elastic arena where the interviewer can ask questions that the narrators are rarely asked by anyone, including people that are close to them. Let’s start from the start. So, that’s rare for anybody.

Mimi, In your opening note to the book you say you want these stories to have what you call a “novelistic level of detail rather than just the case studies.” What do you mean by that?

Lok: If you only see someone as a case study then it normally hones in on that instance or instances of where they had their human rights violated. It’s reducing that person to that moment of injustice. You are reducing that person’s whole experience. We want to do the opposite. I think that most people are, the most that they hear from someone who has been directly impacted by human rights crisis or social injustice, is maybe a quote in an article. It’s really rare that we actually get to hear more than a few sentences from them. The limitation of that is that your understanding of that issue isn’t wrong, but it’s not complete. You are not getting the full picture. Seeing that human rights violation in the context of a life. And in describing that life in the context of the society of that person makes their life. It’s really all about context and seeing how these aren’t just violations that occur out of the blue, in isolation, they are part of some form of systemic injustice. The other side of that is at the core of what Voice of Witness is. It’s having more empathy-based understanding of human rights issues so that you as the reader, as the listener, you identify and empathize with that person’s experiences. You root for them more.

You might have a certain idea or views on immigration or illegal immigration. You sit down with someone who is actually an undocumented immigrant and you hear their whole life story and I’m sure you are going to walk away with some of your preconceptions complicated. It’s really wanting people to have their thinking complicated in a good way. Even if they hear just one story, to think, “I had this idea about what was going on in Sudan or in the West Bank with undocumented immigrants, but I see that it is a lot more complicated than that.” It sounds so obvious saying that, but people don’t often have the opportunity to spend that much time hearing that perspective. It makes for a much richer and much more textured and nuanced understanding of these issues.

The last part is that this approach, this sort of more literary approach, is our way of making the stories more engaging and compelling for their own sake. You don’t have to necessarily have a preexisting relationship or engagement with this or that issue or this or that country, but you just know that if you pick up this narrative you are going to get a really engaging story, a compelling human story.

You’ve been a fairly busy as a writer, Dave, and McSweeney’s has a lot going on. What made you want to devote all the time and resources to this project that you have? Did you see something traveling abroad that showed you how messy the world was and how we weren’t hearing about it? What was the straw on the camel’s back?

Eggers: The real impetus was when Valentino Deng and I were in his hometown of Marial Bai in South Sudan back in 2003. He was reuniting with his family that he hadn’t seen in 17 years. We thought we were doing research for what became “What Is the What?” Meanwhile, we got to meet three young women who had been returned to the village by Save the Children, and all three of them had horrific stories of abduction and enslavement. I had only read the briefest anecdotes about this practice that been reinstituted during the civil war. As a journalist, I just thought the story had to be out there, and people had to know. We just tried to think of what would be an efficient way to tell that story and to allow the narrators to tell their narratives. We thought oral history would be that way. That was what drove it initially. It overlapped with the work at 826 Valencia.

I hadn’t thought of that, but it makes sense.

Eggers: Yeah, over the years we find that oral history is incredibly teachable, that readers really respond to first-person narratives. An issue that seems very abstract and complex becomes approachable and more immediate when told through the eyes of one narrator. We found that again and again with 826. It’s become a major part of Voice of Witness to make sure the narratives are available to teachers and students, that the books are available, that oral history as a practice is available to educators. That’s where they’ve got this really strong education program to make sure that, as a tool for a teacher of English or history or political science or anything, I think there’s nothing more powerful than oral history.

Mimi, How did you get involved personally in this? Why did this seem important and worth throwing everything else aside to concentrate on?

Lok: I did throw a lot of things aside actually. My background is in fiction writing and teaching, and a little bit of journalism in Hong Kong. I came to San Francisco to do my MFA in creative writing and I worked with the writer Peter Orner. About a year after I finished, basically my last year in the country, I was doing a bit of freelance, but I finished up with school and he got back in touch and said, “I’m working on this book on undocumented workers in the U.S.; would you be interested in helping out?” Turns out he was assembling this A-team of documentary filmmakers, attorneys, fiction writers and journalists. Maybe 15 or 20. I hadn’t heard of Voice of Witness as a book project. I was a fan of Dave’s writing, but I had no idea they were doing this book project that was human rights and oral history. That seemed so outside of what I knew that they published. I was really intrigued and as a first generation British-Chinese immigrant I was obviously very interested so I volunteered to join the team.

I spent about a year doing the Chinese immigration beat, interviewing all these Chinese immigrants in New York and in the Bay Area, and it was just a fantastic experience. When I worked as a journalist I was really craving a chance to spend more time with people, but also to have the chance to craft the final piece a little more. But as a fiction writer I always felt a little bit guilty about not having any social contribution to society. This seemed like such an amazing nexus of those two forms of storytelling.

The other thing that struck me about Voice of Witness when it was still in that early incarnation as a side book project was that it is such an important project and there are 15, sometimes 20 of us, working on this project and there are like three functioning tape recorders that we are all fighting over. And there was no money. If we had to travel to an interview we’d use air miles or crash on people’s couches. I just thought this is something that is really important, it needs dedicated staff, it needs dedicated funding, it’s providing a public service. Fortunately, Dave was thinking the same thing. Lola Vollen, the physician who did “Surviving Justice” with Dave and helped conceive of the book series, was thinking the same thing as well.

What kind of larger impact or effect would you like this book or the others to have? You’re getting these stories out to children. You’re spreading the word in all kinds of ways, in which this book is the latest example. What are you hoping for in the long term about this project?

Eggers: I should emphasize: they’re not going to children: I would say the youngest readers are 17 or 18. The teacher in me is just making sure that we don’t share books that are inappropriate for children.

This is understanding [how to see] the world through another’s eyes. Being able to live and breathe another person’s life through their narratives. This is the key to empathy, and I think ultimately, what great books do is they expand our capacity for and practice of empathy. I think that we want to engender that as much as we can, but also bear witness. The two overlap. In a lot of cases, the narrators have not been heard from. They have not been given the opportunity to tell their stories and to make permanent their narratives and to reclaim their narratives.

The goals and effects of oral history and Voice of Witness are many. On the one hand, we want to educate any readers, not just in schools, but the general reader, whether they’re new to an issue and pick up a book like “High Rise Stories” the same way that they would pick up a novel. We hope that those readers come to these stories and their understanding of an issue is deepened and complicated.

On another level, the narrators, we want to give them the right to be heard, and for so many of them whose narratives have been taken from them in a way — if somebody has been called a refugee or if somebody has been called a criminal or if somebody has been called a terrorist — we can allow them to tell their story, to reclaim their narrative, to self-define themselves, and that can be a process of real healing. If somebody’s feeling like they’ve told their story, they’ve been heard, and they have been— and sometimes being heard can be very healing and can make somebody feel a little bit more part of society. Somebody that’s been on the outskirts can feel again heard and that their story is told and printed and is being talked about and used to educate people about a given issue. We’ve found so many of our narrators have become activists, have become very vocal, have sort of become emboldened or strengthened by the process of being heard and having their narratives published. It’s kind of been great on that level, something that we didn’t necessarily anticipate. It’s now a big part of Voice of Witness: making sure that the narrators have all the tools that we can provide for them to become more vocal advocates for themselves and also for the issues raised in the book.

Voice of Witness is a small nonprofit, and we’re trying to plug away and put out a few books per year. We respond to a lot of great proposals and try to advance the cause of oral history for general readers and for educators and students and to just continue to get these stories told.

Oral history has never been an easy sell, to general readers, but I think it’s a shame because books are so readable. We always try to make sure they’re very accessible. It doesn’t have to feel like you’re doing a graduate thesis reading one of these books. They’re very approachable. My hero Studs Terkel made oral history popular and approachable, and we’re trying to remind general readers of what he did and that it can be accessible. We try to do the same thing, and I guarantee you’ll learn something through any of the books.