More than 50 years ago, in the iconic novel “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Atticus sent Jean Louise Finch scouting for what was right and good and fair. Now, in its sequel (or prequel, or even its rough draft), “Go Set a Watchman,” Scout is grown and Jem is dead and Atticus is old and crippled by arthritic hands and a poisoned, racist mind.

Jean Louise scouted so far ahead that now, looking back, she sees Maycomb County, Atticus and Hank with new, open eyes: she sees that all is changed, changed utterly. Her longing for home—for the South—is countered by her powerful, bitter and visceral feelings of repulsion. This push and pull of the South is one of the great tropes in Southern literature from Faulkner to Welty, Wolfe to Gaines.

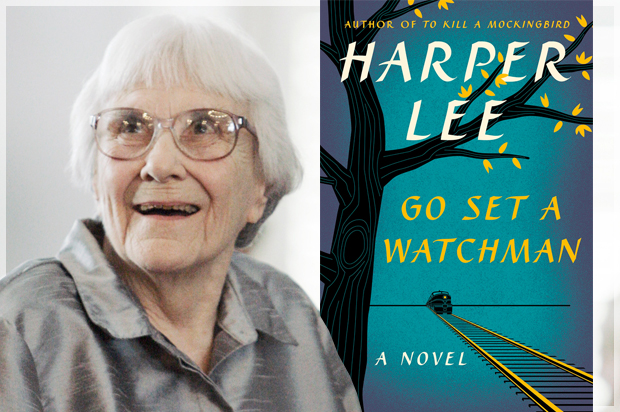

Harper Lee left her hometown of Monroeville, Alabama, as a young woman and moved to New York City. It was there that she wrote about a fictionalized version of her home—beginning with “Go Set a Watchman,” which takes place long after “To Kill a Mockingbird.” Though she wrote about the troubled heritage of her town, her connection with it remained vibrant; she told Life magazine in 1961: “I’m not like Thomas Wolfe. I can go home again.” Harper Lee famously did just that—and stayed there.

Unfortunately, for the readers and lovers of “To Kill a Mockingbird,” it is just as difficult, eye-opening and heartbreaking to return to Maycomb via “Go Set a Watchman” as it proves to be for Jean Louise.

As a transplanted Charlestonian teaching English in New Haven, I am struck by how often my students speak in the past tense when we discuss “To Kill a Mockingbird.” Talking about the Tom Robinson case, my students frequently begin answers by saying: “Well, back then there was lots of racism …”

To many Americans, because the days of overt racism—of colored water fountains and white lunch counters—seem to be behind us, racism itself has whimpered and died. Just two years ago, Chief Justice John G. Roberts acted on this belief when he gutted the Voting Rights Act of 1965 in “Shelby County vs. Holder.” The Act, which mandated that an individual state’s election laws be vetted by the federal government to prevent racial discrimination, was “based on 40-year-old facts having no logical relationship to the present day,” Roberts opined. “Our country has changed,” he wrote. As if racism exists only in history textbooks. As if policy brutality is just a firehouse and a German shepherd. As if nine Charlestonians hadn’t been gunned down by a white supremacist.

The title of the sequel is explained most clearly by Jean Louise’s uncle, Dr. Jack Finch, who tells her that: “Every man’s island, Jean Louise, every man’s watchman, is his conscience.” A changed, racist Atticus reminds us that sometimes, difficultly and heartbreakingly, you must be the watchman over those you love; that sometimes, you have to stand up for what is right and good and fair against those you love.

Atticus’ racism hurt me in a very visceral way. I felt betrayed; how could someone so good believe things so bad? Reading “Go Set a Watchman” is not the first time I have felt that agonizing and confusing disillusionment, though; it is a sensation I am familiar with from having grown up in the South—and along with it comes my shame at remaining silent when those I love say things that I hate.

Jean Louise does not suffer from this same cowardice, for, over the years, she has retained her courage and her sense of fairness. She tells the man she loves, the man who raised her, that he represents that which she hates: “I’ll never believe a word you say to me again. I despise you and everything you stand for.”

I try to ignore the ugly things those I love say because trying to comprehend the discordant harmony in another person erodes the easy labels we prescribe to our friends and family.

I think of my Nana’s father, Leroy, born in the early spring of 1895 in Texas. A man with sparkling eyes and a gentle smile, Leroy was the man who taught my father how to fish and how to tie a knot. When Dad woke up baby Leslie and Uncle Jimmy was going to beat him, Great Granddaddy, with that gentle smile and those sparkling eyes, hid Dad under his chair. But Great Granddaddy was also the man who couldn’t understand why my father would watch “Sanford and Son”—what he called “a n***er show.” How could a man so tender say something so dismissive and merciless? Is my father to hate his grandfather for this? Am I?

I think of Barack Obama’s grandmother, who presented our president similarly conflicting and difficult feelings. He wrote about this in his autobiography, and in 2008, on the election trail and a few months before her death, said: “my white grandmother — a woman who helped raise me, a woman who sacrificed again and again for me, a woman who loves me as much as she loves anything in this world, but a woman who once confessed her fear of black men who passed by her on the street, and who on more than one occasion has uttered racial or ethnic stereotypes that made me cringe.”

When St. Augustine wrote that we should live “with love for the sinner and with hatred for the sin,” he knew that people are complicated beings capable of simultaneous good and evil. As we and Atticus, people (to apply Whitman’s metaphor) are contradictory characters who “contain multitudes.”

Dr. Finch explains the reason for such dissonance to the disillusioned and upset Scout: “As you grew up, when you were grown, totally unknown to yourself, you confused your father with God. You never saw him as a man with a man’s heart, and a man’s failings— I’ll grant you it may have been hard to see, he makes so few mistakes, but he makes ’em like all of us.”

Where “Mockingbird” had the promise of a brighter future embodied in Atticus the wise father, Jem the noble son, and Scout the courageous daughter, “Watchman” gives us the despair we find in a past that lingers. Half of the promise of childhood goodness and innocence—Jem—is dead, and Atticus has come to represent the past that will not pass. The tragedy of “Go Set a Watchman” isn’t that Atticus is a racist; it’s that the hope and promise in “To Kill a Mockingbird” amounted to nothing. Twenty years after Tom Robinson’s martyrdom, Maycomb County is still the sleepy segregated Southern town it always was. What little change has come arose not from within, but from without.

“Go Set a Watchman” is an apprentice piece to the earlier novel’s masterpiece. Something we love and treasure—rightfully so—grew out of this seedling that, by itself, would not stand the test of time. Despite the shortcomings, the difficulties the novel presents us to reckon with add shading to the ways we read “To Kill a Mockingbird” and underscore Harper Lee’s legacy as one of the more Dickensian American authors. Very few have, like Charles Dickens, appealed to so many on such a compelling emotional level or created characters who endure and flourish off the page and outside the book.

Like Dickens, Harper Lee is a great moralist—and she teaches us how to see without much moralizing. Like the wise Fox in “Le Petit Prince,” Harper Lee and Atticus taught us: “It is only with the heart that one can see rightly.” And that which we see sometimes is heartbreaking. Dr. Finch finishes his lesson with what it means to be a watchman: “Remember this also: it’s always easy to look back and see what we were, yesterday, ten years ago. It is hard to see what we are.”

South Carolina state Rep. Jenny Horne, a blood descendant of Jefferson Davis, was the watchman last week at the South Carolina Statehouse. Just as it seemed, in the humid hours after midnight, that the bill to lower the Confederate flag would be tabled in the House of Representatives, Rep. Horne took to the well in the pivotal moment of the debate. Brushing aside the politics of it all, she made it a personal issue about their colleague Sen. Clementa Pinckney. Keeping the flag, she said, “for the widow of Sen. Pinckney and his two young daughters … would be adding insult to injury, and I will not be a part of it!”

Jean Louise, confronted with the disheartening racism of her home, despairs: “I need a watchman to … say here is this justice and there is that justice and make me understand the difference.” Rep. Horne showed us that the time is past when there was a difference between this and that justice. Looking out from her watch post, Rep. Horne called for one justice under one flag. Hours later, Gov. Nikki Haley made that sentiment official.