“So, I saw ‘Magic Mike XXL’ yesterday,” I told a girlfriend over coffee.

She nodded enthusiastically and leaned forward. “I was really surprised by how much I loved it. I mean, that’s not really my thing.”

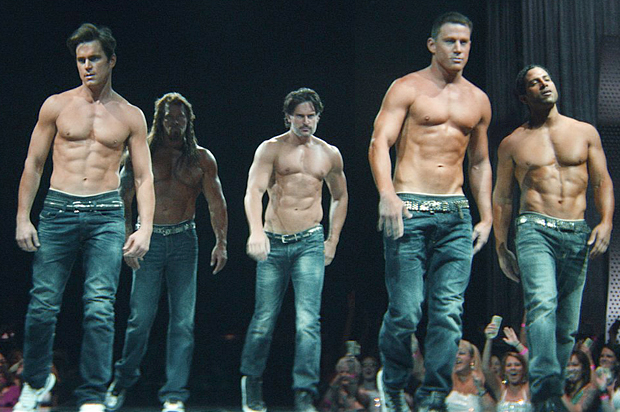

“God knows it’s not mine either!” I rushed to say, before we started reeling off the most feminist moments in this woman-loving brotopia of a film. Was it the reclaimed plantation where black women are alternately sexed up by tWitch and serenaded by Donald Glover? Or Andie MacDowell’s transformation into the campy, growling she-wolf she was always meant to be? Or how about that wafer-thin love plot, whose only kiss is between a woman and her red velvet cake?

I couldn’t help but wonder, though, why we had to swap disclaimers first: “It’s not really my thing, but. . . .” Maybe it was just a verbal pinch of salt thrown over our shoulders, allowing us to move past those silly, sweaty man-bodies poured into their silly, stretchy man-pants to the important things — the feminist things. Or perhaps it was just our version of the old saw about reading Playboy for the articles.

That didn’t seem quite right, though, especially when I began to notice versions of the phrase popping up in enthusiastic reviews of “Magic Mike XXL” by sex-positive feminists. I have no reason to doubt these women when they say that beefy male strippers grinding to “Candy Shop” and “Untitled (How Does It Feel)” on a stage isn’t “their thing” — even if I do know from personal experience that one’s “thing” is often quite a bit more catholic than one is willing to admit in public.

But let’s face it: The most over-the-top performances in “Magic Mike XXL” aren’t necessarily meant to be a literal reflection of our erotic desires. I know of few women who fantasize about being picked up and flipped upside-down while someone mimes cunnilingus into their crotch. And in real life, being stage-humped by a pair of giant sweaty men in front of a packed arena would be, at best, slightly weird, and at worst, terrifying.

Such is reality. But then, cinema isn’t reality, and in a cinematic context, “my thing” shouldn’t have to mean “my thing in real life.” It shouldn’t even have to mean “my erotic fantasy,” or “what turns me on.” It should only have to mean “visual pleasure.” And visual pleasure may be related to sexual pleasure, but it’s not the same thing.

This is something we all intuitively get — as long as “visual pleasure” is understood to mean “men’s visual pleasure.” Men’s visual pleasure is, after all, the wallpaper of our world. Because of men’s historical dominance in the visual arts from painting on up through Internet porn, visuals of naked women in our media doesn’t throw straight female viewers into “no-homo”-style fits. We’re accustomed, if we enjoy film and TV at all, to consuming it with a whopping dose of gratuitous female nudity. This is as true of self-evidently “serious” films and TV as it is of the “Fast and Furious” franchise.

Despite our boob-strewn Netflix queues, however, we don’t assume that grown men are watching either “The Wire” or the films of Michelangelo Antonioni for the boners — not primarily, anyway. No apology is necessary when an adult man looks at a scantily dressed honey, whether he gets a boner or not; it doesn’t even need to be acknowledged. This is why, in his “Furious 7” review, A. O. Scott does not feel the need to assure us that jiggly butts in thongs aren’t “his thing.” We aren’t looking for confessions of sexual preference from male reviewers of films made for the male gaze.

The larger point is that jiggly butts in thongs don’t have to be “his thing.” They’re not there for plot purposes; they’re mostly just there to underscore the fact that men’s visual pleasure matters in the world of the film, and therefore, men matter. I have no problem with either “Furious 7” or jiggly butts in thongs, God bless ’em, but any pleasure I derive from them is strictly auxiliary. And just as jiggly butts and bouncy breasts are a stand-in for straight male pleasure, the hyper-toned, buff, well-oiled dude body is a stand-in for straight female pleasure.

We’ll know that our pleasure really matters when we see a hard-hitting HBO drama where all the meetings take place in a conference room that just happens to look out over the training gym for the men’s Olympic swim team. Picture Jane Russell’s “Anyone Here for Love” number in “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” — but in our version, Russell is briefing legal about the upcoming deposition instead of singing about her unrequited longing for the “physical-culture fans” scissoring their legs all around her.

The joke in the original Jane Russell number, of course, is that the men are — wink-wink — gay. It’s a perfect example of how, historically, over-the-top images of male hardbodies have been coded as gay, just to make it clear that this visual pleasure is still not for women. In our imaginary, lady-centered cinema, it doesn’t even matter whether the men are gay or straight, because gay men in this context exist only for women’s visual pleasure — just as the hot ladies in the “Furious 7” party scenes can make out with each other all day long without anyone mistaking who they’re making out for.

But isn’t this just objectification — the same thing feminists have been railing against for years? Yes, it is, and I suspect that many women’s discomfort with the balls-out beefcake look stems from years of analyzing the effect of such objectifying imagery on women. This is a real concern. Why just flip the script on patriarchy, instead of tossing out the script entirely?

Call me a pragmatist, or just someone who likes movies too much, but I am a firm believer that the objectification ship sailed as soon as the photographic image could be reproduced easily and distributed en masse. In the days when most people lived in villages and images were hard to come by, humans saw comparatively few faces and bodies over a lifetime. As our hunger to look at people is glutted with images of the most gorgeous individuals the world has to offer, hand-picked by the film and advertising industries, our beauty standards have become unrealistic. While asking for more diversity in those images is extremely important, the demand to see perfectly symmetrical people doing sexy stuff is not ever going to go away.

Besides, objectification is only dehumanizing if it is a) mistaken for reality and b) completely unbalanced in favor of one type of gaze. If female audiences were given the scope to explore every nook and cranny of their visual pleasure on film, the way men have for the past hundred years, the result, I believe, would not be a matriarchy in which men only exist to service women’s pleasure. It would be a world with a more sophisticated and nuanced understanding of everyone’s pleasure, male and female, gay and straight. After all, if “Magic Mike XXL” suggests that visual pleasure might empower women to imagine more from their relationships, it also hints that it might enable men to enjoy male friendship more freely, their own sexuality more fully (“Pony,” anyone?) and their frozen yogurt dreams more fro-yo-ishly.

Okay, so it’s a little over the top. But “Magic Mike XXL” is an exploratory fantasy of a world in which women’s pleasure — not just erotic and emotional pleasure, but also visual and narrative pleasure — is always at the top of the priority list. The rock-solid abs and gyrating g-strings aren’t incidental to that vision, whether or not they’re your thing.

And anyway, in real life, red velvet cake isn’t really my thing either. As my husband is well aware, I’d far rather be eating a creamy, crispy-topped crème brûlée. But when I’m watching a movie, I understand exactly what it means for a woman to reach for the red velvet cake that is basically giving her a lap dance, and grab herself a handful.