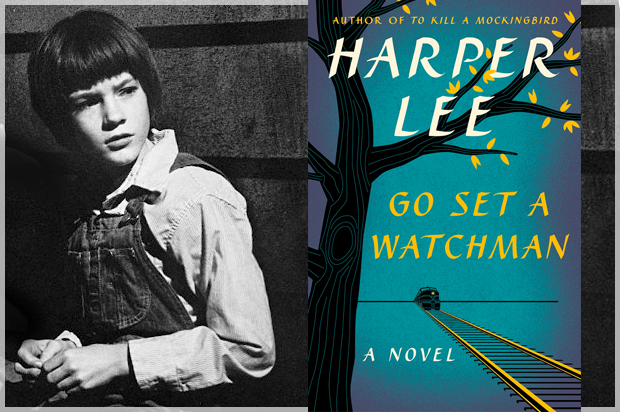

Harper Lee’s “Go Set a Watchman” has gone from being debated and discussed to becoming more than just a media sensation: It has already sold more than a million copies. The sequel, or first draft, or both, to the classic “To Kill a Mockingbird,” the novel brings those characters, including a less benevolent Atticus Finch, into the racially divisive 1950s.

We spoke to Angela Shaw-Thornburg, a scholar of American and African-American literature at South Carolina State University, about the book, its characters, and what they all tell us about where America is now. The interview has been slightly edited and compressed for clarity.

“Go Set a Watchman” has drawn an enormous amount of media attention, and it’s selling like crazy. Why has this book resonated so much?

I don’t know that it’s resonating critically, but for sure it’s resonating in terms of popular appeal. I think it has a lot to do with the fact that Harper Lee was a one-hit wonder. She never published that second book, so people were eager to see more from her.

The other part is that so many people really, really, really loved “To Kill a Mockingbird,” so the idea that people could go back to those much-loved characters — Scout and Atticus Finch — was really exciting to people. But for literary merits, it’s not up there with “To Kill A Mockingbird” in terms of craft and structure.

The earlier novel is very well-crafted. Does this one feel like a gussied-up rough draft?

It really does feel like a rough draft. In “To Kill a Mockingbird” you’ve got a narrator who offers — from her innocence — incisive critical commentary. You’ve got plot twists, thick description of southern Alabama during a particular historical period … It’s good storytelling.

But “Go Tell a Watchman” is not a great story. Not a lot happens! Jean Louise [Scout] comes home, she has a falling out with her daddy, her uncle talks to her, and then her daddy talks to her — and that’s it. If it has any interest it’s for people interested in creative writing: How do you get from that to “To Kill A Mockingbird”?

The other thing that strikes me is not the issue of race, but the issue of gender. Jean Louise says, “I don’t know if I want to get married, I don’t know that I want to come back here, I want to wear my pants …” So she’s a strong female figure; that’s a connection between this work and “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

You were one of the readers not persuaded by Atticus Finch’s nobility in the original novel. I take it you are not surprised by the turn Atticus took, into a segregationist and racist?

No — I teach at a [historically black university], so when I’m teaching these novels, it’s to mostly black students. When most people read “To Kill a Mockingbird,” they’re looking for some kind of racial redemption for us. There’s hope that we can overcome some of our differences, with empathy and principle. But when I read the novel, and think of it from my students’ perspective, I realize there’s not a lot of space given to black voice in that novel. It’s supposed to be a novel about race, about civil rights, but it’s a conversation between white people.

If we’re reading it in historical context, [Lee] wasn’t the only writer doing that. But I’ve never seen it as a big statement about the humanity of black people, and how we need to fight for justice for black people. It’s about supporting the status quo.

The novel comes out at a strange time in America’s racial history: How does this echo against things you see in South Carolina — the state that instigated the Civil War, that recently saw a brutal shooting in a black church, and where the Confederate flag just came down. How does this book, written decades ago, connect to all this?

Oh, absolutely. Part of the interest in the novel comes from the fact that Atticus Finch if a racist — he goes to Citizens Council meetings [and a Klan meeting]. In a way, that’s part of what’s happened in our country. There was a very hopeful moment when Obama was elected: I remember standing in line to vote, and white folks here in South Carolina were like, “We’re gonna put all this racial stuff behind us.” He was supposed to be that kind of redemptive figure. And in some ways he has been.

But in the wake of that, there’s been some real hardening of racist attitudes: Instead of peace and redemption we’re seeing the worst, most vocal white supremacists coming out in force. They’re a small proportion, but my goodness — they’re pretty loud.

One of the things striking to me in this period is finding out what people really think — especially white friends and acquaintances of mine. I would not think they had a white-supremacist bone in their bodies, or conservative views of race, or that they were harboring deep fears about what full participation by African-Americans would look like.

But with the [Confederate] flag, people’s real beliefs and feelings are coming out. I’ve been off of Facebook for the last couple weeks because I’ve been, “I really didn’t want to know that about you.”

That kind of schizophrenia, where people say, “Some of my best friends are black …” On a small scale they can see individual African-Americans as human beings; on a large-scale issue, they’re not able to. It’s almost schizophrenic: On one hand we have an Atticus who says he’s all for justice, on the other hand he goes to Citizens Council meetings. I think this is a very accurate perspective of what’s going on here in the South. It’s part of our DNA. We have racism, but we get really upset if people are rude and crude. The two novels together are an accurate view of where we are as Southerners.

You write in your review that the Civil War isn’t really over. Tell us what you mean by that.

When Dylan Roof went into that church and studied the Bible with them for an hour, and then went back and shot them, that was one of the ghosts of the Civil War. He took it to an extreme; he massacred those people. But these battles go on, especially at the level of rhetoric. Especially here in the South, we engage in a lot of dog-whistle politics, where people appear to be speaking about the so-called underclass but they’re really talking about race.

The South has had an outsize impact on our politics. We’re continuing to fight this war. Are we going to include all people — and I don’t just mean black people — in American democracy and society, or not? Or are we going to be an exclusive society of haves and have nots? This war between people who have money and power and land and those who don’t — that’s continuing. Here in the South, it’s sometimes expressed in terms of race and class. But that war is ongoing — people can’t let it go.