Some researchers say that growth, or the perception of growth, might be influenced by culture. Americans in particular are bombarded with so many messages about the need to learn from and benefit from adverse experiences that trauma survivors here might be telling themselves that they have grown in order to conform to a cultural norm. People are certainly influenced by the culture around them. And stories of post-traumatic growth are everywhere from ancient history to religion, in the lives of our most celebrated people and even in popular culture. Everyone has been exposed to these tales. They are some of our best-known and most powerful stories.

One of the most succinctly rendered and best-known stories of post-traumatic growth first appeared in 1939. It was only two illustrated pages long and told the story of a young boy who watches as his parents are senselessly murdered by a robber. Then, just days later, the boy is shown at his bedside offering this prayer: “I swear by the spirits of my parents to avenge their deaths by spending the rest of my life warring on all criminals.”

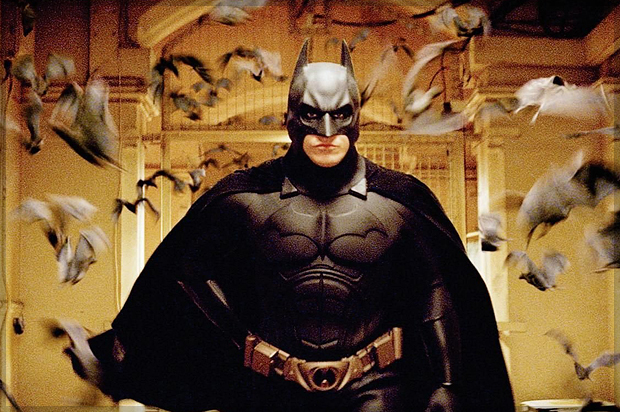

The young boy, of course, is Bruce Wayne, and he takes on the character of the superhero Batman to fight crime and protect the city of Gotham at all costs. As depicted in that early comic strip, he is transformed—almost instantly—by the brutal murder of his parents. He is motivated to become a “master scientist,” to become physically powerful, and to dedicate his life and his sizable fortune to a broader altruistic cause: fighting crime and protecting others.

For those who worked on the series for more than seventy years after it was conceived, it was clear that this story moved readers and tapped some fundamental experience that fans easily identified with. Dennis O’Neil, who edited the series on and off between the 1970s and 2000, was given the chance to change Batman’s origin story. “I said no,” he says. “In this one sentence—Batman saw his parents murdered when he was a child—we have everything we need to know about him. His motivation is literal. Everything is perfect.”

Batman isn’t the only superhero who is transformed by loss. Peter Parker in the Spider-Man series begins using his powers to fight evil only after the tragic death of his uncle. The Green Lantern witnesses the death of his own father in a plane crash. The Flash’s mother was murdered. Loss and transformation is a constant theme.

Despite the superpowers and fantastical story lines in these comics, those who developed the stories of these superheroes were inspired by real people. Paul Levitz, who wrote and edited for DC Comics for forty-two years and was its president from 2002 until 2009, had an outsize role in shaping the stories of American popular culture. And for him, the tale of post-traumatic growth was not only an engaging one that connected with readers; it was fundamentally grounded in the story of another well-known American: Teddy Roosevelt.

Roosevelt was born into a powerful and wealthy family, but as a child he suffered from severe asthma, which left him confined indoors for much of his childhood. He developed an especially close relationship with his father, who often stayed up late at night with him when he was sick. When Roosevelt was in college, his father died suddenly of cancer, which he’d hidden from the family. As a way of honoring his father, Roosevelt dedicated himself to public service, an unusual choice for a wealthy young man at the time. Roosevelt was driven to achieve. By the age of twenty-four he was already a New York State assemblyman. Two and a half years later, in February 1884, his first daughter, Alice, was born.

Then, just two days later, tragedy struck. Roosevelt’s wife and his mother died within hours of each other.

The young man was shattered, writing in his journal, “The light has gone out of my life.” Roosevelt withdrew from public life, left his infant daughter with his sister, and headed west to live on a ranch in North Dakota. He built a cabin and raised cattle. Roosevelt took off on long hunting trips where he shot grizzly bears and other big game. Sometimes he rode on horseback alone for days through blizzards and below-zero temperatures, pushing himself to physical and psychological extremes. He found a remarkable fearlessness, confronting gunmen who threatened to kill him and hunting down cattle thieves. But when he slowed down, grief would overwhelm him.

Eventually Roosevelt returned to New York and was appointed to run New York City’s police commission. He took to the streets and walked officers’ beats to ensure that they were doing their jobs. He exposed corruption on the force and locked horns with powerful and deeply corrupt political figures. He patrolled the city alongside muckraking journalists. Roosevelt, in his time with the commission, became a transformative force for reform, much as he would later as president.

Almost seventy years after Batman’s origin was divulged in those two succinct comic book pages, Christopher Nolan, who directed the 2008 Batman film The Dark Knight, based parts of the film on Theodore Roosevelt’s life and urged its star, Christian Bale, to read a biography of Roosevelt. Nolan found inspiration in Roosevelt’s story, just like Levitz had during his career at DC Comics. It became a touchstone to shape the stories of other superheroes, stories that have helped people to understand how adversity can change them. “People succeed in wonderful and dramatic ways in history,” says Levitz. “And that provides the inspiration for what the heroic journey can be.”

That heroic journey—the archetype of many of our oldest stories—is at its core a story of post-traumatic growth. Joseph Campbell, who studied myths of cultures around the world, discovered common themes hidden in those stories. The archetypal myth of the hero, one of the most common stories, begins with the protagonist leaving his or her home, or at times with the destruction of a home. Then the hero is presented with a series of challenges, often traumatic or violent ones, sometimes involving a trip to the underworld. At the end of the journey he or she returns home, often avenging wrongs and becoming a changed and enlightened leader.

The theme of post-traumatic growth can be found in Homer’s Odyssey, in the stories of the knights searching for the Holy Grail, in Dante’s Inferno, in the four-thousand-year-old myths of the Sumerians, and in modern-day shamanistic cultures, says Evans Lansing Smith, who traveled extensively with Campbell and is now the chair of the mythological studies program at Pacifica Graduate Institute, which is home to the Joseph Campbell Collection. The theme continues through Batman to today’s superheroes. The story of growth is as old as our oldest recorded history and seems to appear everywhere.

These stories of growth have certainly influenced our culture. But they are also grounded in real people’s lives. Theodore Roosevelt’s life experience, and the ways that loss and grief molded him, helped to inform the stories of comic book characters for decades. And those characters in turn influenced the way that everyday people think about adversity, change, and their own potential. So, certainly people are influenced by their culture and do develop expectations about how they should react to trauma. But that culture is also influenced by real-life figures who go through real psychological processes. They grow because people often do grow. And the stories that result reflect that. Our myths are not made of fantasy.

And, it turns out, these concepts of trauma, growth, and change are not simply a creation of Western culture. Tzipi Weiss, associate professor of social work at Long Island University’s LIU Post campus, examined how culture influences post-traumatic growth in a book she coedited, Post-traumatic Growth and Culturally Competent Practice: Lessons Learned from Around the Globe. Weiss reviewed published studies of trauma survivors from more than a dozen different cultures. She found studies that reported post-traumatic growth in Israelis who survived terrorist attacks and Palestinians confined in Israeli prisons, in Turkish victims of earthquakes and Chinese breast cancer survivors, and in other populations around the world. “It’s pretty clear that post-traumatic growth is a universal phenomenon,” she says.

And perhaps that is why Tedeschi and Calhoun’s work has caught on. Researchers around the globe are pursuing questions about growth from every angle in dozens of cultures. In fact, growth has become part of an entirely new way of understanding trauma, as not just a temporary setback or an illness-inducing event, but as a fundamentally transformative experience—one that changes people psychologically, and even alters the way their brains function. As Tedeschi and Calhoun theorized decades ago, researchers from an array of fields are discovering that trauma causes fundamental change. “It’s pretty mind-boggling,” says Calhoun of the entire field of study he and Tedeschi sparked. “We’re not even Chapel Hill, let alone Harvard or Princeton. It feels very good.”

Excerpted from “UPSIDE: The New Science of Post-Traumatic Growth” by Jim Rendon. Copyright © 2015 by Jim Rendon. Used by permission of Touchstone, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.