“Rapid response team” comes over the PA system and I wait, holding my breath, to find out where. “Medical Oncology.”

Shit! Our floor? Which room? “It’s here! It’s Mr. King!” I hear Nora. She’s in the pod next to mine.

I walk back to her, fast, and see Susie coming down the hall, fast, too, with Randy behind her. Nora has already pulled the crash cart into the room and I see, quickly, Mr. King, a patient most of us have known for over two years, lying in bed not moving with a thin stream of blood running from his mouth down his chin onto his chest.

My focus narrows to what’s right in front of me: the portable defibrillator is on the bed next to Mr. King. I grab the small plastic instrument we use to measure oxygen saturation and stick his finger into it.

“What’s his pulse-ox?” asks Nora.

“Waiting.” The machine registers a horizontal line as it calculates Mr. King’s oxygen level. “Seventy-five percent.”

“I’m cracking the cart, getting out a non-rebreather.” That’s Randy.

I hear Susie say, “What happened to him?” as I wrap the blood pressure cuff around his arm and start the machine so we can get his pressure.

Nora says, “I dunno. I walked in and found him like this. Here—you can record.” She shoves a clipboard at Susie. “Write down everything that happens on this form.”

Susie’s eyes widen, but she takes the clipboard and clicks her pen open.

Suddenly the room floods with people: an ICU doc, nurses from the ICU, a respiratory therapist, an anesthesiologist. The code team has arrived.

This intensivist, Matt, is a friend. Despite not being any older than I am he’s world-weary, but also whip smart with a well of compassion hidden beneath his hard edge. He stands by the opposite side of the bed, across from me, and our eyes briefly meet. Then he raises his voice above the loud buzz in the room. “What’s up with this patient? Who’s the nurse?”

Nora’s good in codes. She rolls the information out like she’d memorized it. “Day one hundred – plus of a mud transplant, patient has GVH of the lungs and a fungal pneumonia, with increasing needs for oxygen. Alert and oriented with occasional moments of confusion, bed-bound due to weakness. Walked in this morning and saw him . . . like that, non-responsive. O2 sats 75 percent, so we put him on a non-rebreather.” She points to the breathing apparatus now covering Mr. King’s nose and mouth.

“His sats now?”

“Eighty-eight percent on twelve liters.” Twelve liters is the maximum amount of oxygen that device can give and 88 percent is far below normal, which hovers between ninety-five and one hundred percent.

“Heart rate?”

“Fifty,” someone calls out as Matt flips through Mr. King’s chart.

“Pressure?”

“One hundred over eighty,” I say.

“Let’s get some blood gases,” he tells the respiratory therapist.

“What’s his pressure? And what’s his platelet count?”

“One hundred over eighty,” I say again, louder this time, but I’m not sure Matt hears me over the ICU nurse calling out, “We have a bed! He can go to A222.”

Nora also calls out at the same time, “Platelets are ten—he’s refractory. No HLAs available.” With a platelet count of ten, people can bleed spontaneously, and although we’ve been transfusing him regularly, his platelet count barely rises each time. (HLAs are platelets matched to Mr. King’s blood, but we don’t have any on hand. They can be hard to get.)

“Do I get to hear a blood pressure or not?” Matt demands.

I look at him and raise my voice. “It’s one hundred over eighty,” I say very loudly and he nods to himself. “OK, we’ll take that bed. Pack him up and move him out. He’s stable enough to transfer—we’ll intubate him downstairs if we need to.”

“Can we take him down in your bed?” the ICU nurse asks Nora. “We’ve got time—we can do it for you.”

“You’ll return our defibrillator? And the bed?”

“Uh . . . no. But you’ll have to bring down his meds and give report. You can take them back with you then.”

I have a sick taste in my mouth. Mr. King was my patient when he was first diagnosed over two years ago. He’s gone up and down, but I thought he was in an up-phase. I haven’t taken care of him for a while, though, so he must have gotten worse without my hearing about it. Having blood drip from his mouth and pool on his chest is unsettling since it suggests he didn’t notice enough to spit or even turn his head to let it dribble out.

“Aspirated.”

“He aspirated.” It’s a low murmur, passed person to person. Some of the blood from Mr. King’s mouth went down the wrong tube, into his lungs.

“Has anyone called Opal?” I say. His wife. She’s tough and resilient, but not prepared for this turn of events, at least not the last time I talked to her.

“I called her,” says the nurse practitioner who’s permanently on the stem cell transplant team. Mr. King is one of their patients. “She can’t come right away, but as soon as possible.” They live more than an hour’s drive away and he’s been in and out of the hospital for two years. God knows how she’s keeping the rest of her life going in between times.

Nora, Randy, and the ICU nurses gather Mr. King’s things—framed pictures, extra pairs of pajamas—and put them in some of our “patient-belonging bags.” He’ll have a lot less room in the ICU. Opal will have to take some of it home, I guess.

Matt has signed off on the rapid-response sheet that Susie filled out and starts to walk back up the hall when I flag him down. I lean in closer to him and keep my voice low. “What do you think his chances are?”

“Slim to none,” he says, like he’s swearing, and I hear in his voice that note of concern masked by resignation that made me like him the first time we met.

“That bad?”

He grabs my arm. “Theresa, we’re all gonna die.”

“Right. I know. But I like him,” I say, trying not to sound childish.

“If you really like him, then wish for the family to put him on hospice so we don’t have to keep all this up in the ICU.”

“No chance that he’ll make it?”

He stops and looks at me for a minute without speaking. We’re about the same height and our eyes meet. “His lungs are junk, we can’t stop him from bleeding, and he’s got an opportunistic infection that’s barely under control.”

“I’d forgotten about the infection,” I say in a low voice, mostly talking to myself.

“Wish for hospice,” he tells me, firmly, and we both start walking again.

At my pod we wave good-bye to each other. “Thanks for looking on the bright side.”

He gives me a pained smile, then, “That’s what I’m here for.”

The ICU nurses start to roll Mr. King down the hall. A housekeeper will clean the room, making it ready for a new patient. Nora will give report to the nurse in the ICU, just like the day-shift nurses all got report this morning, then come back upstairs and record everything that happened on the computer. Susie documented during the code, but that was on paper. Half an hour, forty-five minutes, and the emergency is over, except it feels like Mr. King took a piece of my heart with him, and he wasn’t even my patient today.

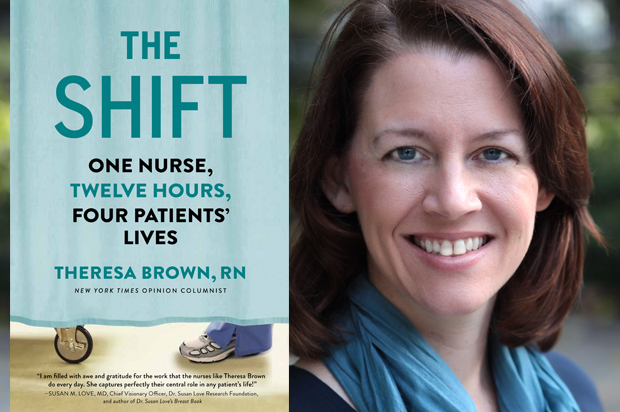

Excerpted from “The Shift: One Nurse, Twelve Hours, Four Patients’ Lives” by Theresa Brown, RN. Copyright © 2015 by Theresa Brown. Reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.