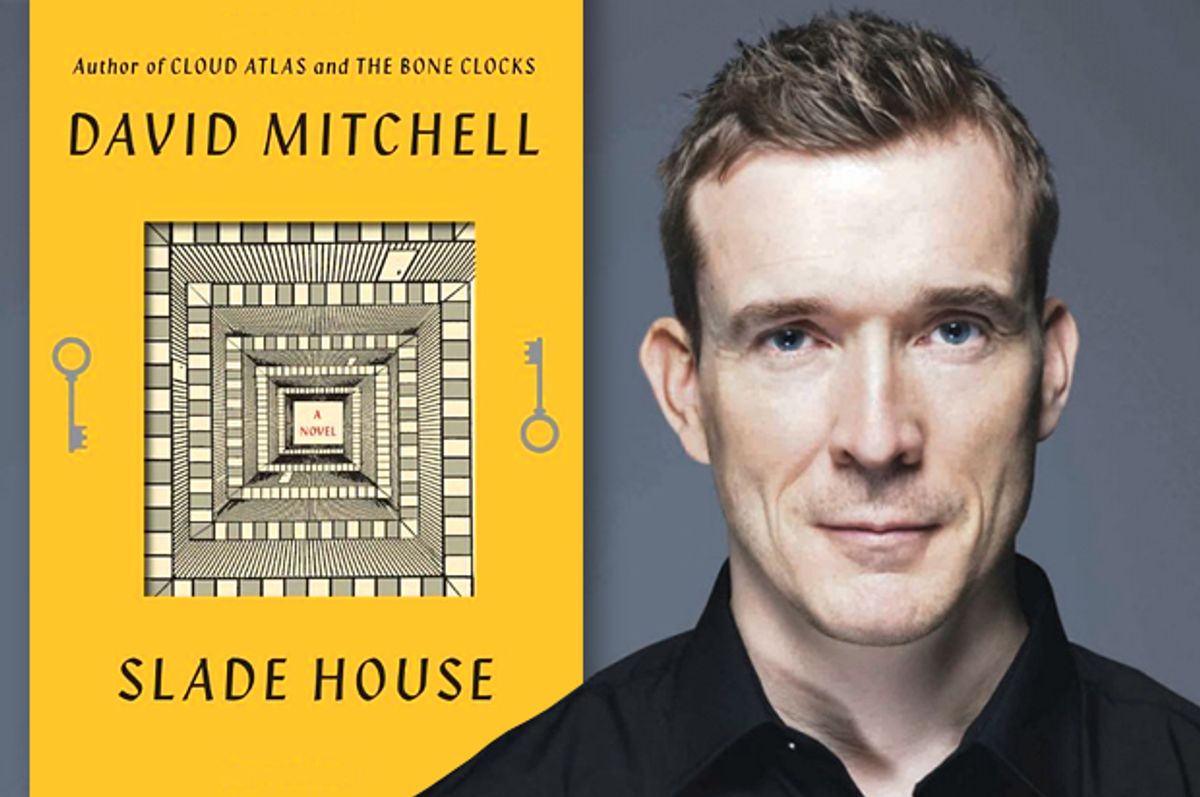

David Mitchell is known for reasonably long, complicated novels that jump around in time and space and post daunting, unanswerable philosophical questions between the lines of their narrative fun. He’s a hedonist, an intellectual and a literary magpie, able to evoke the voices of writers from Herman Melville to Ursula K. Le Guin.

Mitchell’s slim new novel “Slade House” pumps up the hedonism and tones down the complexity a bit: Though it’s told in five sections that range from 1979 to 2015, it takes place in and around a lavish, mysterious estate down a brick alley. And instead of the usual jumping around in genre -- from the seafaring story to the thriller to the post-apocalyptic novel -- this is mostly a strange and eccentric haunted house novel. Anthony Doerr calls it “a ‘Dracula’ for the new millennium, a ‘Hansel and Gretel’ for grownups, a reminder or how much fun fiction can be.”

We spoke to the Englishman from Ireland, where he now lives. The interview has been edited slightly for clarity.

You begin through a series of tweets. Where did the idea of writing it this way come from, and did it shape the way your write?

It came from the fact that I had a Twitter account and was feeling a little bit bothered by underusing it essentially as a notice board for saying, “I’ll be doing such and such an event at such and such a place on this day....” I was thinking that this technology exists, and could I use it for anything that would interest me?

I’m not really interested in describing day-to-day details of my life, and random thoughts I have throughout the day. I understand that some people get pleasure from doing that, and that’s fine. But of course, I want to keep my private life the way it is. So, I couldn’t use Twitter for that reason.

However, using it artistically, now that began to interest me. Could I use it to do what I do anyway? Could I use it to get excited about what I get excited about anyway? A narrative. So I began to think about Twitter fiction and what would that look like, and how to do it so it wouldn’t just be a gimmick? Is anything inherent in the nature of Twitter that would validate a particular type of story?

And the idea that I got: a kid, in the story, I mean, who has an unusual mind and is somewhat overwhelmed by reality, perhaps sensory processing problems or maybe a bit what we might now call Asperger's or something on the autism spectrum, though in 1979 [when the story is set] the terms really didn’t exist then.

Suppose this kid is overwhelmed by reality, sees it as a cubist, pointillist difficult-to-process place, and then purloins some of his mom’s Valium tablets. And instead of reality being this impossible four-dimensional rush, it gets distilled, slowed down and packaged into these steady, consistent short pulses – these packets of information, rather like a tweet. Now, I had that idea. I felt I had something that would justify using Twitter to tell a story because there is something in the story that marries up with the nature of Twitter.

So, then it’s just a question of which story? I had some ideas that were originally going to be in a very early version of “The Bone Clocks,” but “The Bone Clocks” kind of moved away from them because it didn’t work on the page. There was nothing wrong with the idea, but “The Bone Clocks” didn’t need them anymore. I tried to put them into the book, but it was against the book’s will; it would’ve broken the book.

One of those ideas was to have a diabolical engine in the form of a house that exists to transfer or distill the souls of guests into the longevity of the creators of the machine, which might start to sound familiar to anyone who has read “Cloud Atlas.” So, the first story,” The Right Sort,” I did to see what it would be like, whether it would work.

And here I am at last answering the second question in your opening couplet, which is whether it changed the way I write? Yes… You need to construct the story out of glimpses, which is analogous to seeing a landscape from a high-speed train going through a sequence of tunnels into valleys, where you get blasts of light, blasts of information, then you're back into a tunnel again, then you’re out into another sunlit valley.

You have to spin four plates at once. You’d spin the plates of counter-development, plot, ideas, and maybe also of style.

On the page, you can do this simultaneously. It is sort of like a balloonist’s-eye view when your write ordinarily, like looking down on the landscape of the story all at once rather than racing through it almost at light speed, also at high-speed train speed. So, you only have enough space in each pulse to do one thing. Each tweet can only do one of those four. It can only develop the character, it can only advance the plot, it can only present an idea, or it can only be beautiful for its own sake, and give the reader a little kiss of something strange and lovely – just through language and style. So, you have to alternate these, and make sure that the plate has started to wobble and is in danger of falling.

You also have to have relatively short names because if a name is as long as Robert Zimmerman III, half your tweet is gone before you can do anything else with it. Or Benedict Cumberbatch would be a deathly tweet name because most of your tweet is gone.

It is funny because for readers, the book is light-hearted and, well, more fun than some of your other books. It sounds incredibly difficult to do what you’ve just described. Is opening with that tweet-driven section the hardest thing you’ve ever done as a writer?

Not really. The story already existed in my head. It was a question of converting that to tweets. If something isn’t working – and that’s normal, they normally don’t work – then you just backtrack to the place where it started to get off the tracks, find out where it went wrong and fix it. If you fix that, you move on to the next scene and the one after that. Then, surely, something about that doesn’t work, and you work out what’s gone wrong there.

The challenge lies is adapting what you do anyway. In a way, it was just like any other straitjacket that as a writer you put yourself in to then perform an act of escapology to get out of it again. The act of escapology is that of writing a book that works.

In a way, the more devilish the straitjacket is in the first place, the more interesting and we hope, watchable, audacious and perhaps original the act of escapology ends up being.

So, the more problems you stack up for yourself in the beginning, the more dividends you can reap as the book nears its end. Because as you’ve made it hard for yourself, that also makes the book less like anything else the reader's encountered before. So your short-term problems, challenges and difficulties end up being your long-term friends and allies.

I think of your work as being largely shaped by science fiction and fantasy, but this book is closer to a haunted house story or horror story. I’m curious about your interest in that lineage – horror movies, Poe stories…

Anything that is good grabs me, irrespective of its genre. The idea of confining an entire genre as being unworthy of your attention is a bizarre act of self-harm. So, “The Shining” is a great book. “The Haunting of Hill House” by Shirley Jackson is a great book. “The Turn of the Screw” is just one of those two flawless novellas; that and “Heart of Darkness.” There is nothing wrong with it. Nothing. It is absolutely as word-perfect as “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” by Yeats. Or as one of those brilliant short poems such as “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” by Robert Frost, but it’s hundreds of time longer. Now, that is difficult. Writing “The Right Sort” is a piece of cake compared to that.

On the British side, we’ve got W.W. Jacobs’ “The Monkey's Paw,” a short story about a guy whose friend comes 'round, he's back from India, and he's got this shriveled monkey's paw. He throws it in the fire when his friend says, “What's that?” He says: “A magic paw. It grants three wishes.” And the friend gets it out quickly, or maybe he's about to throw it onto the fire. And he says, “Well, I'd like three wishes.” And the friend says, “Uh-uh. Are you sure? You really want to think this through, because they may not be granted to you in the same way that you're expecting them.”

I mean, it's only about 15 pages long – and it's easier to write a 15 page-long short story that's perfect than to write “The Turn of the Screw,” which is much longer – but it's still a perfect short story. So him, [and] M.R. James – curious, sort of scholarly, in a way not very frightening but there's something disturbing in the texture and atmosphere .... Not much appears to be going on when you read them, but it's all in the atmosphere. And that's really rather brilliant. That’s a few.

Dickens wrote “The Haunted House.” That was almost a novelty piece. He wrote one section of it and then he had about five friends who wrote other rooms of the haunted house. Some are good, some are less so, but it's a really interesting exercise as well. He's also got one of the first frightening things to see in a mirror. When you look in the mirror it's not a ghost, it's not a doll, it's not a demon, it's not a witch – it's nothing but the face of your very elderly father looking back at you rather sadly. It's a chilling thing to see in a mirror.

It's such a great idea that I nicked it and used it in “The Bone Clocks,” actually. So you can trace that back to him. And there's an Irish supernatural/horror story writer – he's brilliant – called John Connelly. And he's a modern inheritor of the traditions we've mentioned.

There's a late version of Japanese ghost stories as well that's very much in the culture, these sort of Buddhist, Shinto-flavored ghosts that are very satisfying. And there are some wonderful monsters in popular folklore – some really quite bloodthirsty, really quite disturbing – that are part of the culture. And every Japanese person I've ever met, just – you can try this yourself if you know anyone from Japan – just ask them about Hanako-san, who lives in the school toilets. She's there at every school toilet in the land. And she's absolutely terrifying if you don't know the code, if you don't know how to placate her. Then she'll have you. I think every culture has its traditions of ghost stories. And it's fun not just to read British and American ones but ones from some other countries.

You live in a small town in Ireland, a country you didn't grow up in. I imagine it being fairly isolated. I wonder if for you to write, is it important to have a lot of time to yourself? I mean, some writers get their energy from being around people. How does it work for you? Do you need long hours or days of solitude?

I have to be a chameleon who can adapt to the circumstances that I find myself in. I like the idea of thinking: No, I have to be alone for days on end before I can properly germinate and gestate and bear fruit… But I don't think that would wash with my family, to be honest. I've got school runs to do. I've got meals to fix. I've got washing up to do. I’ve got a washing machine to empty. I've got supermarkets to fit in, just like everyone else.

So I need to see what span of time I have available in any given day, fill it as efficiently as I can, make sure I don't succumb to clickbait when I'm online, and quickly get back to writing the scenes that I need to write that day. So that's how I work. It may be that at some point in my life I will have these free acres of time – but somehow I doubt it. And I'll be acting accordingly then. But right now, I have to be the chameleon.

Let me close with one issue that was talked about when “Bone Clocks” came out – the way that all of your books fit together. I guess I have a smallish question and a larger question… I'm wondering, do you want “Slade House” to be a book that people can jump into cold? You know, people who haven't read “The Bone Clocks” or the other David Mitchell novels?

Oh, yes. Yes, most certainly. That's the first principle. The second principle is that my books can fit together and be read as very loose chapters in a kind of über-novel that I've spent my life writing and will spend the rest of my life working on as well. But that's only the second principle. The first principle is that every book I write has to be enjoyable for a reader who's never read anything I've written before, and will never read anything I write again. So they do need to be stand-alone pieces of work that work as novels independently. So that, I guess, is your short question. And the longer one behind that?

Yeah, maybe this is short too. You've now, as you've said, linked all of your work into a single universe. Tolkien did it – you're not the first writer to do it.

Ooh. Certainly not.

But I wonder if that limits you at all? Does that draw any barriers as to what you can do? Or do you feel like you still have many possibilities open?

I believe – I may be wrong – but I believe it does not limit me in any way whatsoever. I'm not working on a series. This isn't “Game of Thrones.” It's a little bit different. It's a universe, that's the right word for it. And all universes are vast places, and they have their own realms and different quarters and contain different genres as well. So in a way it's like having my cake and eating it.

I do like large-scale enterprises, but one of the attractive things about Middle Earth is its vastness. It has its ancient history and its now. And it's the size of two continents, at least, in space, and five historical eras at least. And that's attractive.

But I'm too sort of promiscuous as a writer. I'm too hungry to also be a minimalist to write stories, narratives that are very different from each other, with a lot of clear water in between them. And this construction of a very large universe in a somewhat piecemeal way, rather than in an adjacent way. Yeah, it lets me be the maximalist that I am, as well as the minimalist that I am. So no restrictions that I'm aware of. I'm probably about halfway though now, in terms of the number of books that I'll write in my life, if I don't get hit by a bus next week.

Right. Or have your soul taken by –

…My soul extracted. So if I haven't found the limits yet, I suspect they're not there.

Shares