Over the last few weeks, campus protests have grown around a number of figures from American history: Protestors have argued that because of a record of racism, Woodrow Wilson, John C. Calhoun, and Jeffrey Amherst should have their names removed from institutions and, in some cases, statues removed from schools they are associated with.

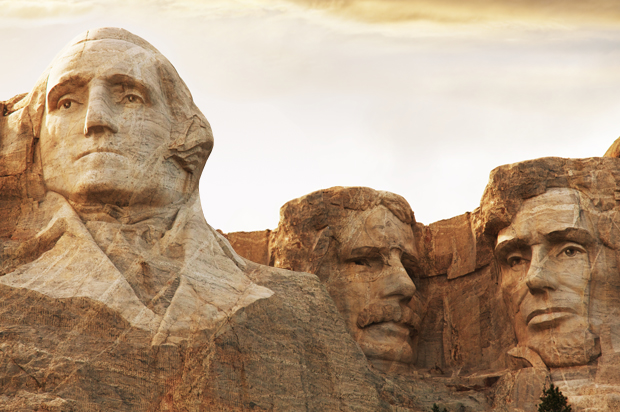

Thomas Jefferson’s connections to racism and slavery have been known for a long time. And now a tide seems to be building against him, too. “Many observers have wondered which historical figure honored on American campuses would next capture critical attention,” a story in Inside Higher Ed reports. “The answer appears to be Thomas Jefferson. At both the University of Missouri at Columbia and the College of William & Mary, critics have been placing yellow sticky notes on Jefferson statues, labeling him — among other things – ‘rapist’ and ‘racist.’ “

Will anti-Jefferson sentiment build, or will it be checked by his contributions, like his role in the Declaration of Independence? Are these charges fair to Jefferson? Salon spoke to Stephanie McCurry, a historian at Columbia University who specializes in the 19th century and the American South. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Let’s start with the charges made against Jefferson. Are they fair?

Let me just say it does seem to be an extraordinary moment of national accountability for slavery and its aftermath. I’m cautiously optimistic that this moment has finally arrived, and it’s interesting why it’s coming now. There’s nothing about it I regret.

What historians know turns out to be kind of explosive when it becomes a matter of public knowledge: There’s an element of, “Did they not know?”

I never liked the idea of the Woodrow Wilson School; I could never separate his ideas of race from his ideas on what Progressivism was. So the idea that they were connected – that’s an important recognition.

And looking at Yale, with Calhoun College, or Princeton, with the Woodrow Wilson School, and various buildings named after Wilson, and now with Jefferson, it makes it incumbent on us to sort through what we want to come out of these long, long overdue conversations.

Part of what you’re saying is that educated people, including informed undergraduates, have been aware of some of this for a long time. But there wasn’t this kind of uproar? What’s changed?

I wonder that this has to do with another significant public intellectual development, which is the work of people like Ta-Nehisi Coates, which brings deeply informed [ideas] to a public forum inviting people to learn with him to understanding our past, other racist and imperialist regimes.

Part of it is connected to what African-American citizens, African-American students on campus, think is bearable… I’m not at all disturbed by this conversation: I think they’re fully entitled to have their say.

Some of these things are very easy calls: Students should not be forced to live in a residence hall named for John C. Calhoun. I know the complications of this, involving alumni giving, for instance… But I don’t think African-American students should be required or even invited to live in a residence hall named after Woodrow Wilson.

There was [an op-ed] in the New York Times about a man [whose ancestor] had a very direct and personal experience with [Wilson’s] segregation of the civil service. These are things that need to be known… To ask that man to live in a residence hall… “Congratulations, you have been admitted to Princeton University, you are now a resident of Woodrow Wilson Hall!”

How does Jefferson fit into all this?

To get back to Jefferson: When I go to [the University of Virginia] to do research, I’m always profoundly uncomfortable with the reverence for Jefferson on that campus. It’s just inappropriate. I teach about Jefferson… I find Jefferson compelling as a historical figure, precisely because of the very knotted relationship between ideas of America.

I’m a foreigner – I’m Irish. My route into American history was Jefferson, and the shocking ethical dilemma posed when I understood that the man who wrote the Declaration of Independence was a slaveholder: This was not something I knew until I was an undergraduate. That to me is the nub of one of the great ethical challenges of American history.

So was Jefferson a racist? Yes, but as I tell my students, sometimes the more salient question is, Who’s an anti-slavery racist and who’s a pro-slavery racist? In the 19th century world I teach, there’s a world of difference between those two things.

In the end, Jefferson created a more profound pro-slavery America… But at the same time, he did write the Declaration of Independence.

The question of his sexual predatory character: Is it a profoundly uncomfortable fact that he appears to have initiated a sexual relationship with a child [Sally Hemings] who was, what, 15-and-a-half years old when she was attending his daughter in Paris and seems to be initially in a sexual relationship with Jefferson? You’d have to check Annette Gordon-Reed’s book [“The Hemingses of Monticello”], but she was very young. A child, alone, on the other side of the Atlantic, enslaved – it just evacuates any question of consent, it seems to me.

So then do you want to make the move of calling him a rapist? Well, I haven’t. But I don’t really mind if someone puts a post-it note on Jefferson’s statue asking that question.

It sounds like you think the debate is healthy. Is the best way to deal with this kind of thing to take down statues and rename institutions?

I’ve just begun to try to work through this myself.

The question of taking down statues and obliterating their history and our veneration of it – that really requires some thought. In this country, far less than other countries with traumatic pasts, we have not had a public reckoning yet, with slavery and the Civil War, in a way that we need to. It’s astonishing the extent in this country the way the Civil War is regarded as the moment of redemption: We’re probably the only nation that commemorates its Civil War as a celebration.

So these projects on universities and racism and slavery – these are really important developments. I don’t think we should all eradicate [statues and names], but when people like Brian Stevenson manage to do more on their own, with a philanthropic organization, to mark the sites of slave sales and markets than any government or public historical unit, than something is wrong. It’s kind of shameful, actually, that that was left to the labor of an individual.

So this is not just a matter of tearing things down as much as putting things up.