With the help of the mainstream media, Donald Trump is fueling a deep-seated nativist paranoia that has a long history in this country. Loud-mouthed political bullies have been part of the American political system since its earliest days. America’s past is littered with the legacies of political demagogues like Trump and some of his Republican cronies.

With the help of the mainstream media, Donald Trump is fueling a deep-seated nativist paranoia that has a long history in this country. Loud-mouthed political bullies have been part of the American political system since its earliest days. America’s past is littered with the legacies of political demagogues like Trump and some of his Republican cronies.

Here are six demagogues from American history who riled up Americans’ basest instincts.

1. John Adams (1735-1825). One of the nation’s Founding Fathers, Adams led the first anti-immigrant and anti-free-speech campaigns, and his efforts were successful. He led the congressional campaign to pass four laws in 1798 known as the Alien & Sedition Acts. As the second president, Adams warned of the dangers of foreign influence within the U.S. and said they must be “exterminated.”

In the wake of the French Revolution and the ongoing wars between France and Britain, the nation was divided. The Federalists, led by Adams, backed the British and were opposed to the radical ideas inspired by France Revolution, while the Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, were more sympathetic of the French. The battle over the Alien & Sedition Acts was posed as loyalty to the Constitution versus loyalty to the U.S. government. Jefferson’s election in 1800 ended the tyranny of the Alien & Sedition Acts.

2. Millard Fillmore (1800-1874) was the 13th president. After leaving office in 1853, he championed a virulent anti-immigrant movement know as the Know Nothings. The movement grew out of the Second Great Awakening or the Great Revival of the 1830s and became the American Party, which flourished during the late ’40s and early ‘50s. It got its name when members were asked the party’s positions and simply said, “I know nothing.”

Religious intolerance led to numerous anti-Catholic attacks, including the burning of churches, random beatings and the killings of ostensible Catholics in Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington and Louisville, where 22 people were murdered. In the 1850s, the American Party captured the Massachusetts legislature in 1854; in 1856, it backed Millard Fillmore for president, who secured nearly 1 million votes, a quarter of all votes cast. The movement collapsed in the face of the Civil War.

3. A. Mitchell Palmer (1872-1936). As attorney general from 1919 to 1921, he recruited J. Edgar Hoover as a special assistant to oversee what became known as the Palmer Rails, the mass arrest and/or deportation of alleged subversives. In the wake of WWI, he warned that communism was “eating its way into the homes of the American workman.” The Sedition Act (1918) expanded the Espionage Act of 1917 to cover the expression of any opinion that cast the government or the war effort in a negative light.

In June 1919, Palmer’s Washington D.C. house was bombed, followed by bombings in seven other cities killing two people. In response, Palmer launched a series of raids. On Nov. 7, 1919, on the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution, over 10,000 alleged communists and anarchists were arrested on suspicion of planning a revolutionary uprising. No evidence was found, nevertheless, Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman and another 245 people were deported to Russia. On Jan. 2, 1920, Hoover rounded up another 6,000 alleged subversives, who were held without trial. Following Palmer’s announcement that a communist revolution was likely to take place on May 1, mass panic took place. In New York, five elected socialists were expelled from the legislature.

4. Karl Bendetsen (1907-1989) was the architect of Japanese-American internment during WWII. While the FBI and the Office of Naval Intelligence found that the vast majority of Americans of Japanese ancestry were loyal, Bendetsen took a hard line against all Japanese Americans. He drafted what became known as Executive Order 9066, which President Franklin Roosevelt signed on Feb. 19, 1942, ordering the forced relocation and incarceration of between 110,000 and 120,000 Japanese Americans living along the West Coast. Nearly two-thirds (62%) of those interned were loyal U.S. citizens. Bendetsen ordered that any person with “one drop of Japanese blood” had to be interned, including infants and children in orphanages and even hospital patients, some of whom died on the way to a prison camp. He even opposed Japanese American soldiers serving in the war effort from returning to the West Coast.

In 1988, Pres. Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act to compensate more than 100,000 Japanese Americans who had been incarcerated in WWII internment camps. The legislation offered a formal apology and paid out $20,000 in compensation to each surviving victim.

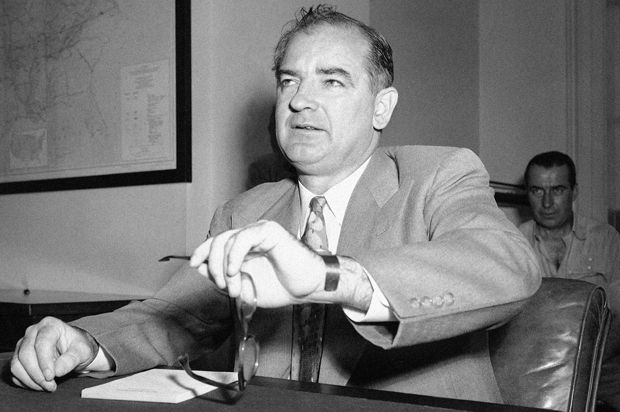

5. Joseph McCarthy (1908-1957). In February 1950, Sen. McCarthy (R-WI) announced in Wheeling, WV, “I have in my hand a list of 205 cases of individuals who appear to be either card-carrying members or certainly loyal to the Communist Party.” McCarthy’s list was never formally made public and he kept changing the number of alleged communists depending on the audience he was addressing

McCarthy investigated communist subversives as well as “homosexuals and other sex perverts” working for the government. In 1953, he held hearings at New York’s federal courthouse grilling subversive writers, notably the novelist Howard Fast, newspaper columnist Drew Pearson and Louis Budenz, the former editor of The Daily Worker. In 1954, in a hearing over alleged communists in the U.S. Army, he had his legendary showdown with Joseph Welsh, council to the Army. Walsh asked simply: “Have you no sense of decency, sir?” The encounter broke McCarthy; he was stripped of his committee chairmanship and died in ’57, a drunk, defeated man.

6. David Duke (b/1950). This neo-Nazi political pugilist has sputtered at the periphery of U.S. politics for nearly five decades and now calls Austria home. Earlier this year he came out for Trump, reportedly declaring, “Trump is really going all out. He’s saying what no other Republicans have said, few conservatives say.”

As a student at Louisiana State University, Duke was enamored of George Lincoln Rockwell, founder of the postwar American Nazi Party, who he called “the greatest American who ever lived.” In 1970, he founded the White Youth Alliance, a student group affiliated with the National Socialist White People’s Party. A couple of years later, he founded the Knights of the Klu Klux Klan, and in the words of the Southern Poverty Law Center, oversaw the “Nazification of the Klan” by shifting its ideological target from racism to anti-Semitism.

In the late ‘70s, looking to move up the political food chain, Duke ran for a seat in the Louisiana Senate as a conservative Democrat but lost. In 1981, he set up the National Association for the Advancement of White People, which a critic called, the “Klan without the sheets.” In ’89 and running as a Republican, he won a special low-turnout election to the Louisiana State House, and in 1990, he ran in the primary for a U.S. Senate seat and lost. The following year he ran for governor—it was a runoff election with the Democratic candidate, Edwin Edwards, and Duke lost again. In 2002, his past caught up with him; he was arrested and pleaded guilty to felony mail and tax fraud charges and he served 15 months in a federal prison and was fined $10,000.