Mass hysteria over the conspiracy theory of government “death panels” may have been the key to rallying massive opposition to health care reform in the summer of 2010, but it only managed to make the end result more compromised, not to kill it outright. Still, the “death panels” conspiracy theory played a key role in reviving and rearticulating conservative power after the Bush years ended in calamitous disaster—a rearticulation that has been overwhelmingly negative, thus leaving the door wide open for the likes of Donald Trump.

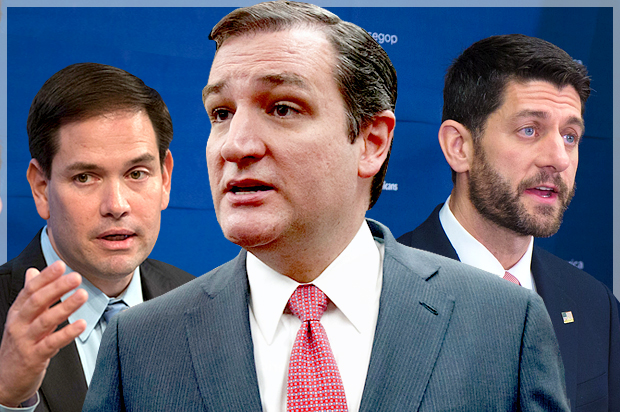

Now, after years of seemingly endless contentless promises, votes and pledges to “repeal and replace” Obamacare, there are rumblings that Republicans will actually try to do something next year. The American Enterprise Institute has released its “Agenda for Reform,” and in a blog post about it, Physicians for a National Health Plan explained that it was important to know what they had in mind, noting that “Speaker of the House Paul Ryan has promised this next year a comprehensive Republican plan to replace the Affordable Care Act.”

The only problem is that the core of AEI’s reform plan—the magical power of “empowered consumers” and “consumer-driven healthcare”—is every bit as mythical as the death panels were. The only difference is the death panels were Evil! Evil! Evil! while empowered consumer-driven healthcare is Good! Good! Good! At the L.A. Times, Michael Hiltzik explained:

Among the holy grails of would-be healthcare reformers, the holiest and grailiest quest is for the “empowered consumer.”

This creature, armed with discernment about his or her medical needs and free choice of doctors and hospitals, will bring us to the paradise of low-cost medical care and uncompromisingly good health.

Just like deregulating the financial sector made us all as rich as JP Morgan, right? It’s a similarly ludicrous con-job, but with a somewhat different fatal flaw: Health care costs are heavily concentrated among a relatively small number of very sick people—the top 1 percent of spenders account for more than one fifth of all spending, the top 5 percent for almost half—and no amount of pundit incantations will magically turn them into “empowered consumers.” Meanwhile, the bottom 50 percent account for just 3 percent of spending. In terms of cost, they don’t seem to need any fixing at all. Yet, paradoxically, they’re the best candidates for acting like “empowered consumers.” The top 5 percent are simply too sick, too desperate to qualify.

This high concentration of need is just the most glaring example of how deeply the “healthcare market” differs from the textbook fairytale of a perfectly competitive market, the natural habitat of the unicorn, I mean the “empowered consumer.”

As Hiltzik breaks it down, “true consumer-driven healthcare requires three things,” price information for competing providers, reliable outcome data, and “consumers who are inclined or able to base their healthcare decisions on the first two factors.” The first two are difficult enough to obtain—comparative outcome data “are hard for even trained clinicians to determine, and even then only after years of research,” Hiltzik notes, “expecting patients to have this data at hand is chimerical”—but the third is virtually impossible. As already noted, the sickest 5 percent, accounting for 50 percent of costs, simply aren’t able to base their decisions on price and outcome data. But what about the rest?

Here, too, there’s an utter divorce from reality. Hiltzik quotes Amitabh Chandra of Harvard from a piece at Forbes, where he’s identified as “center-right,” in a piece aimed at mapping out middle-ground positions. “Simply calling a patient a consumer doesn’t make buying healthcare like buying cars,” Chandra said. “In healthcare, the consumer (i.e. the patient) is sick, tired, confused, distracted—they want their doctor or their insurer to help them manage the health-care that they need. Making them deal with a high-deductible plan is double jeopardy: first, they get hit with an illness. And then we hit them financially and cognitively. It’s not fair. And it doesn’t work.”

But high-deductible health plans [HDHPs] are one of the key elements in the AEI approach. They put consumers’ “skin in the game,” which is what “empowers” them to “make smart choices” and “drive costs down.” It all makes perfectly wonderful good sense—magical, even—just like unicorns and virgins. But the internal logic of the fairy tale has nothing to do with the real world, except in superficially misleading ways, as Chandra explained:

There is no industry which has reduced costs without engaging customers. So it’s tempting to think that we can do this in healthcare—through a combination of “skin-in-the-game” health plans (a.k.a. high-deductible plans) and transparency tools to encourage shopping.

But Chandra studied the actual workings of such a plan, a “natural experiment that occurred at a large self-insured firm with tech-savvy and well-paid employees,” he explained. If ever there was a group of consumers prepared to be “empowered,” this group was it. And at first, it really looked to be working:

This firm moved its employees from an insurance plan that provided free healthcare to a non-linear, high deductible plan. The switch caused a spending reduction of 12%— so HDHPs certainly save money. A 12% saving is really large. If the result is general, it implies that moving everyone to such plans would save about $300 billion annually!

Sounds great! Except, that’s just what I meant by “superficially misleading,” as Chandra goes on to explain:

But once we peeked under the hood, what we saw really troubled us. First, we found no evidence of consumers learning to price shop after two years in high-deductible coverage. None. So strike one. We also found that consumers reduce quantities across the spectrum of healthcare services, including potentially valuable care (e.g., preventive services) and potentially wasteful care (e.g., imaging services). So they don’t know what care is valuable and what isn’t. Strike two. We then leverage the unique data environment to study how consumers respond to the complex structure of the high-deductible contract. We find that half of all reductions come for the sickest consumers, while they are under the deductible, despite the fact that these consumers have quite low end of year prices as a result of their sickness. In other words, consumers respond to prices but they’re responding to the wrong prices—they don’t fully understand the complicated structure of the HDHP. Strike three.

And that’s what a center-right expert had to say. It’s not surprising, really. The first modern welfare state, Germany’s, was established by conservatives—partly to steal the socialists’ most popular idea and undercut their political support, and partly to meet a number of conservative’s goals: slowing the flow of emigration to America, making German industry more able to compete with Britain, reinforcing elite/state power and gender roles. Conservatives elsewhere either followed suit or came to support welfare states created by others. And health care is a key component in all such systems. Only U.S. conservatives have such a visceral, long-standing animosity to what conservatives elsewhere recognize as a practical, efficient way of dealing with basic human needs that simply don’t fit into the Coke-or-Pepsi consumer preference market model. Make that elite U.S. conservatives, since the overwhelming majority of self-identified conservative voters have no interest in having their Medicare and Social Security taken away from them—which is one reason Trump appeals to them much more than AEI does.

Also cited by Forbes is Martin Gaynor, of Carnegie Mellon University, identified as center-left. He cites “two things that, in my view, mean that consumers are not going to drive this market.” The first is the concentration of spending, and the second is that “consumers don’t respond effectively to the cost sharing features of health insurance plans,” the exact same point that Chandra made. So center-left and center-right are basically agreed: no unicorns.

Further evidence comes from a December report from McKinsey & Company, “Debunking Common Myths About Healthcare Consumerism,” which draws on survey results from more than 11,000 people in just the last year. Two of the eight myths they cite are relevant here. The first is, “Consumers know what they want from healthcare companies and what drives their decisions.” But the survey evidence suggests “there is often a disconnect between what consumers believe matters most and what influences their opinions most strongly.” Specifically, they found that “empathy and support provided by health professionals (especially nurses) had a stronger impact than outcomes did. Satisfaction levels were also strongly influenced by the information the participants had been given during and after treatment.”

The second, “Most consumers research their healthcare choices before making important decisions and then make fact-based choices based on their research.” Regarding this, they reported:

Five different surveys we conducted recently suggest that many, if not most, healthcare consumers are not yet making research-based decisions. Our findings indicate, for example, that only a few consumers are currently researching provider costs or even the number of providers they can choose among. Although some (but far from most) consumers are beginning to research their health plan choices, many of them are not yet aware of key factors they should consider before selecting coverage.

…. [E]ven among the subset of consumers who reported doing research on costs before undergoing an expensive, invasive procedure (e.g., cardiac or joint surgery), half still said that their doctor’s recommendation was the key factor that influenced their decision about where to seek care.

Cost is our primary concern here, given the thesis that empowered consumers will drive down costs, but consumers’ lack of information is much broader than that:

Cost is not the only factor most consumers are not yet actively investigating. In last year’s CHI survey, we asked the participants who reported having been hospitalized in the previous three years to tell us how many hospitals there were in their local area. More than half said there was only one local hospital when, in fact, there were a median of three hospitals within a 10-mile radius of their home and ten hospitals within a 20-mile radius.

Such lack of knowledge is neither surprising nor alarming in the real world. If you know about the hospital where you’ve gotten good care (90 percent said they had, according to McKinsey), what difference does ignorance of others make? It’s important for the “empowered consumer” unicorn theory, since it’s essential for unicorns to drive down hospital costs by forcing them to compete. But people, unlike economically hyper-rational, omniscient unicorns, most often rely on their doctor’s advice in major medical decisions—such as which hospital to go to. Which is why such limited knowledge should neither shock nor worry us in most cases. But it should shock and worry AEI’s unicorn theorists, since it’s a really big problem for them. If there are no unicorns, alas, the unicorn theory falls apart.

Of course it’s possible that people could be trained to act and think differently, to become unicorns, given enough time—5, 10, 20 years, maybe. But with 50 percent of them accounting for only 3 percent of spending, that’s an awful lot of re-education for very little gain. If “the customer is always right,” then shouldn’t the solution be to design the system to serve customers as they are, rather than forcing them to all turn into unicorns instead?

AEI’s self-styled freedom-loving crew love to rail against liberals and government bureaucrats forcing people to conform to their utopian blueprints. But there’s nothing utopian about government-ensured universal healthcare. Virtually every other advanced industrial nation has it—and has had it for decades, if not generations. What’s utopian is AEI’s vision of empowered consumer-driven healthcare—a “system” that’s worked nowhere on earth, not even for unicorns. Not only are the AEI crowd the real utopians; they’re also the ones who want to micro-manage others’ lives to fit into their utopia. Neither Obamacare, Medicare nor Medicaid requires people to become abstract models of someone else’s idea of perfection. But that’s precisely what AEI’s vision requires. If you’re not an economically hyper-rational, omniscient unicorn, then you’d damn well better learn to become one—because it’s their world that AEI is preparing for you to live in.

There’s one further irony here. The folks at AEI aren’t conspiracy nuts, particularly. They’re much more representative of the conservative elite side of things. But they have much more in common with the unruly GOP base than they’d care to admit. As already noted, they’re incredibly cut off from reality, and wrapped up in their own fantasy land, just as conspiracy theorists are. That’s one thing in common between more libertarian conservative elites and their unruly populist base.

But this isn’t just an accidental or incidental similarity. The death panels conspiracy was floated and proved so wildly popular precisely because conservative elites had run out of plausible positive alternatives, but had an existential need to “just say no” to Obama. Conservative elites don’t want to own conspiracy theories, but they just can’t survive without them—especially now that they’re taking aim at Social Security and Medicare. They’ve been fumbling around for years, searching for ways to sell this poison to the rubes in their base. And that’s what the AEI plan is, once you strip away all the unicorn talk—another way to sell their base on getting screwed out of their Medicare. It’s a conspiracy theory turned inside-out: Don’t let the evil government stop us! We’re gutting your Medicare for your freedom! After all, the AEI plan’s first principle is “Citizens, not government, should control health care.” And by “citizens,” of course, they mean unicorns.