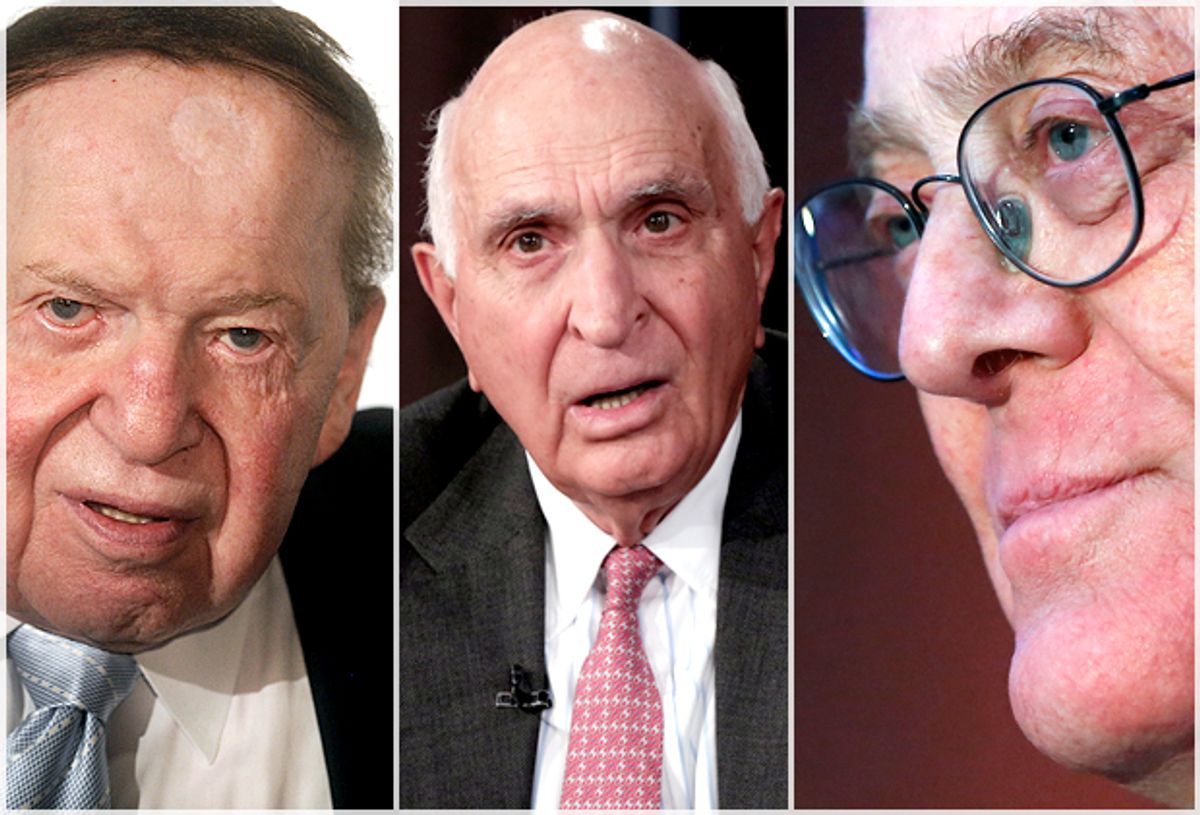

With the strange and increasingly tawdry scandal around billionaire Sheldon Adelson's not-so-secret purchase of the Las Vegas Review-Journal still unfolding, and with Charles Koch still complaining that he lacks sufficient influence upon American politics, finding a balance between American democracy and the American legal system's understanding of free speech is as important as ever.

Yet ever since the Supreme Court's 2010 Citizens United decision (arguably, even before that, with its Buckley v. Valeo decision in 1976) holding the debate on free speech grounds has always been treacherous — at least for those who believe in not only donor transparency but active government regulation. It seems that so long as money equals speech, and so long as political spending is treated as a form of speech just like any other, reform will be either thwarted or in retreat.

That's the intellectual breach into which campaign finance reformer and activist Derek Cressman has stepped with his new book, "When Money Talks: The High Price of 'Free' Speech and the Selling of Democracy." Rather than simply hold the same debate and wait for demographics to hand Democrats a victory in the end, Cressman's book urges supporters of reform to challenge some of the basic assumptions underlying campaign finance reform's political terrain. That includes the prevailing legal understanding of "free speech," yes; but it also pertains to the reform camp's vision of what is and isn't possible, too.

Recently, Salon spoke over the phone with Cressman about his book, the campaign finance reform movement, and why he thinks activists are much further along the road to a workable system — one that preserves both free speech and real democracy — than many realize. Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

What made you want to write a book?

Well, I’ve been thinking about the problems of money and politics, and, in particular, how the courts have exacerbated those problems for about 20 years. We’ve reached a point in the organizing to pass a constitutional amendment that would establish that money is not free speech, and that we’re really starting to be taken seriously. That’s a great progress, but it also means that as we enter a more serious stage in the debates, we’re seeing oppositional arguments. I felt it was incumbent upon the proponents of that amendment to clearly articulate what we’re trying to accomplish --- to rebut some of the spurious attacks against it. So, that was one of the reasons for the book.

The other is that I am still somewhat astonished at the number of people who simply think it is impossible to overturn a misguided Supreme Court ruling. And yet, if you look at our history, that’s far from the case. Part of my objective is to do some of that research and present it to people, providing a road map for the many different ways for reversing Supreme Court rulings.

Your book begins with the intellectual argument in favor of reform before it moves on to the practical questions of what is to be done. Could you lay out that argument for me?

The biggest argument that we’re seeing from opponents comes from basically an intellectual sleight of hand. They are conflating free speech and the free press with paid speech and advertising. What I am demonstrating in the book is that those are two very different things, and we can draw a fine line between those two.

What the First Amendment offers is very stringent protection for freedom of the press and free speech, and the ability to speak your mind without government censorship or retribution that must be distinguished from paid advertising, which is paying to put information in front of you. Given the very nature of our brains, being very limited in the amount of information we can absorb, when you are bombarded with information from one source, you are displacing information from other sources, and limiting or squelching other speech.

That’s the way we need to start looking at this issue, which is different from how both courts, and reform proponents and opponents have talked about it for 40 years, which is mostly through this lens of corruption and bribery that was first locked onto in the Buckley v. Valeo case.

How do we draw that distinction about different kinds of speech?

The essence of it is asking whether the reader or the listener is speaking out information, which is the realm of free speech. You need absolute protection to buy whatever book you want or subscribe to whatever newspaper you want to read or watch whatever movie you want to watch, including a movie critical of Hilary Clinton such as that produced by the Citizens United organization. That is one side of the line: speech that is sought out by the listener.

The other side of the line is information or speech that is hoisted upon the listener through spending money, and that is obviously like 30-second TV commercials, but also direct mail flyers. When you get on your computer and do a Google search, there are some organic results that are there through the content mechanism that Google has paid, and that the readers are seeking. And there are also paid search results that are there as a result of paid advertising. I like that example because it is within the same medium. It is all there on your computer screen, produced by Google, yet some is paid speech and some is free.

You believe that reformers should pursue a constitutional amendment. But a lot of people — including very, very dedicated advocates — think that’s basically a nonstarter because amending the Constitution is so difficult. Why do you disagree?

On its face, I refuse to accept the notion that 80 percent of the country cannot govern itself in the way it sees fit, and that we must yield to five men, wearing black robes, who get to control the country and set the rules. That is just a complete abandoning of the idea of self-government. It is an unacceptable premise. Ultimately, it is a politically unsustainable proposition to think that any tiny group of powerful people can prevent 80 percent of the country from governing themselves the way they want to.

I just think it can’t be true that it is impossible. Historically, when you look at it, we have solved more critical problems than this before. We didn’t even used to have the right to vote for our U.S. senators. So, we’re seeing a tax on voting rights now, and they’re mean and ugly, but at least, you can still vote for a U.S. senator. And as you can imagine the incumbency in the U.S. Senate, where they loathe changing the process, where they used to be appointed in a ... often corrupt relationship through state legislators, and suddenly having to face the voters. They weren’t interested in that, and bottled up that reform that eventually became the 17th Amendment for 60 or 70 years. But ultimately, the overwhelming majority of people found a way to prevail and to get that changed.

So, after we get people over the hurdle of disillusionment, what are the next concrete steps?

Some of them, I think, are obvious and well known to people. For example, you have presidential candidates right now saying that they will make this issue a litmus test, appointing Supreme Court justices according to their position on Citizens United. But some of the tools that I am hoping to bring back to light are things called a voter instructions process, and this was a widely used tool at the time of America’s founding, where columnists would get together and elect someone to present them in the continental and U.S. Congress. They would, in general, say, “We’re sending you there because we trust you, and you know our values, and you’ll be able to stand in our place.” But occasionally, they’ll give them very specific marching orders, which are known as constituent or voter instructions.

This was a process that was used to draft the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution. And it is a process that has been used through several of the amendments to the Constitution. Strangely enough, it has been largely forgotten. So, a lot of the work that I‘ve been doing in the past five years or so has been to revise that idea. Some of that we did in 2012 with voter instruction measures in Montana and Colorado. There have been dozen of municipalities that have held these votes. They tend to go overwhelmingly in favor of instructing Congress to pass constitutional amendment by margins of about 3-to-1. And I spell out in the book the suggested language that city councils could use as an instruction measure on the ballot. And that is one tangible, immediate thing that readers and citizens could do, which is to start working and place these questions on the local ballot, and giving their community the opportunity to debate this issue and speak on it collectively as the electorate and as the people.

A lot of the action is going to happen on the local and state level, at least for now. So what should we be asking of national politicians?

I think for presidential candidates and candidates to the U.S. Senate, it is appropriate to ask them about the Supreme Court nomination and confirmation process, and whether or not we can count on those candidates to make this an issue that would weigh in their decision to nominate or confirm a member to the court.

Secondly, we’ve already seen a vote on [an] amendment in the U.S. Senate, so incumbents have gone on the record on that. Reformers and reporters should be asking them to explain those votes, and asking challengers how they would vote on that issue. I think maybe the most fundamental issues, especially in the House of Representatives, which isn’t involved in the Supreme Court nomination process is: Will you represent your constituents or not? It is widely known and documented in every public opinion survey you can take that the overwhelming majority, ranging from two-thirds to higher than 85 percent, think that the Citizens United ruling was wrong. So, as the job of a member of the House of Representatives is to represent her or his constituents, will they do that or will they represent the extreme ideologues and the billionaires, who are funding their campaigns on their absurd notion that campaign advertising is the same thing as free speech?

Is there a gap between the media’s interest in campaign finance reform and the interest of the general public?

I think we are seeing a significant increase in the media coverage of this issue, and of candidates talking about this issue compared to when I started working on these issues in the late 1990s. That said, I think that a lot of the coverage and candidate rhetoric is basically belaboring the problem in pointing out that things are corrupt or certain politicians are taking huge amounts of money from special interests or that things are unfair, which everybody knows. So, reporting on the obvious is not a particularly useful service to readers from a news service point of view. From a candidate point of view, I feel that they are dodging solutions.

Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton are exceptions. They have put out a fairly detailed platform with some specifics in there. So, that has been an improvement since the beginning of their campaigns, but most of the other candidates focus on corruption. You hear Donald Trump get up in the debates and talk about how money buys politicians, and we do it all the time without talking about how to fix that. I think that’s what is still lacking in the debate.

Are you optimistic about reform’s chances? It can feel like those who support reform are taking the first steps on what looks like a long, daunting, hard road.

People often feel daunted by the long-term nature of this project, and I am the first to acknowledge it. If you look at our history, it has often taken anywhere from 50 to 70 years to pass a constitutional amendment and right most of our wrongs. What I think most of us fail to realize is that we are 40 years into this struggle that really did begin in 1976 with that first act of judicial activism in Buckley v. Valeo. It took 10 or 15 years of people like Sen. Ernest Hollings laboring away on the floor of the U.S. Senate in complete obscurity. Nobody even knew this debate was happening. So, reaching this point, where we are having a national debate about it reflects 40 years of work and progress. I think that rather than people taking that look back, it is more encouraging to look forward and realize that we’re not in the beginning of this struggle. We’re well into the middle of it.

Shares