“Food Stamp recipients didn’t cause the financial crisis,” said President Barack Obama in his final State of the Union speech on Tuesday. “Recklessness on Wall Street did.”

That’s also the message of “The Big Short,” a fascinating film that looks at how bankers’ greed led to the 2007 mortgage meltdown, the implosion of the housing market, the near-collapse of the financial industry, and the breakdown of the whole economy, including widespread layoffs and foreclosures, from which we have still not fully recovered. Producer Brad Pitt (who also has a quirky part in the film) and director Adam McKay clearly viewed the film as an indictment of the banking system and its insatiable appetite for profits and wealth. They wanted to elicit the audience’s outrage at how the bankers’ short-sighted gluttony caused so much suffering among millions of Americans through no fault of their own.

There’s much to be outraged about. In the late 1990s, banks and private mortgage lenders began pushing subprime mortgages, many with “adjustable” rates that jumped sharply after a few years. These risky loans comprised 8.6 percent of all mortgages in 2001, soaring to 20.1 percent by 2006. That year alone, 10 lenders accounted for 56 percent of all subprime loans, totaling $362 billion. As the film explains, these loans were a ticking time bomb, waiting to explode.

After the 2007 meltdown, housing prices nationwide fell by a third. Families lost nearly $7 trillion of home equity. More than 5 million homeowners lost their homes. Millions of middle-class families watched their major source of wealth stripped away, their neighborhoods decimated, and their future economic security destroyed. The drop in housing values affected not only families facing foreclosure but also families in the surrounding communities because having a few foreclosed homes in a neighborhood brings down the value of other houses in the area. The neighborhood blight created by the housing collapse was much worse in African-American and Hispanic areas because they were the primary victims of subprime loans and almost twice as likely as whites to lose their homes to foreclosures.

As “The Big Short” reveals, the crisis had both winners and losers. The real culprits didn’t pay for their crimes. The film’s narrator — Jared Vennett, a smarmy trader for an investment bank, played by Ryan Gosling (based on Deutsche Bank trader Greg Lippmann) – explains that Congress bailed out the banks with more than $700 billion in taxpayers’ money without insisting that they change their practices. Gosling’s character also reminds us that only one banker (Kareem Serageldin, a senior trader at Credit Suisse, who was convicted for inflating the value of mortgage bonds) has gone to jail.

Since 2009, 49 financial institutions have paid various government entities and private plaintiffs about $190 billion in fines and settlements (according to an analysis by the investment bank Keefe, Bruyette & Woods) but the payments have come from shareholders, not individual bankers. Many Wall Street honchos survived the financial crisis not only with their jobs intact but with substantial raises. A study by the Institute for Policy Studies found that the bonuses handed to 165,200 executives by Wall Street banks in 2013 — totaling $26.7 billion — would be enough to more than double the pay for all 1,085,000 Americans who work full-time at the current federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour. In early 2014, soon after JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon settled out of court with the Justice Department, the bank’s board of directors gave him a 74 percent raise to $20 million.

All this is true, but it is only part of the story – and the part that the film leaves out is what’s needed to put the banking crisis in a bigger, and somewhat more hopeful, perspective. The movie’s coda informs us that despite the enormous damage done by Wall Street, little has changed. That’s simply not true.

So what’s missing from “The Big Short”? For starters: Dodd-Frank, Elizabeth Warren, Occupy Wall Street and Bernie Sanders. We’ll get to those in a bit.

* * *

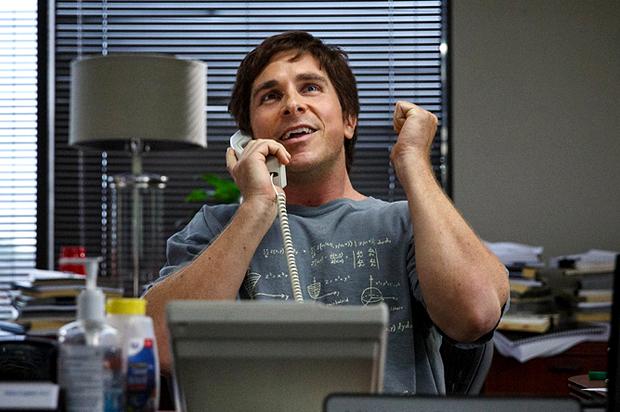

“The Big Short” — which garnered five Academy Award nominations, including best picture, director, adapted screenplay, editing and supporting actor (Christian Bale) — focuses on a handful of financial industry misfits who recognized how the upsurge of subprime lending put the entire banking system at risk. In some ways, McKay portrays them as the heroes of the story, even though they used their insights to make money rather than to blow the whistle.

In fact, several years before any of the characters in the film understood the fragility of the financial system, others were sounding the alarm. Community groups like ACORN and National People’s Action learned about the subprime rip-offs from their low-income members and tried to pressure government officials and lenders to end these predatory schemes. Brooksley Born, chairwoman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission from 1996 to 1999, wanted her agency to regulate derivatives and other exotic financial investments (including credit default swaps) that she accurately predicted were too risky and would lead to disaster. But President Clinton’s Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, economic advisor Larry Summers, and Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan stopped her from exercising the kind of regulatory authority that would have prevented the calamity.

In 2000, Edward Gramlich, a Federal Reserve Board member, repeatedly warned Greenspan about subprime mortgages and predatory lending, which he said jeopardized the twin American dreams of owning a home and building wealth. He tried to get Greenspan to crack down on irrational subprime lending by increasing oversight, but his warnings fell on deaf ears. In 2001, the Center for Responsible Lending, a research and advocacy group, issued a report alerting regulators about the dangers of the upsurge of subprime lending. Yale economist Robert Shiller also tried to warn regulators that the housing bubble was about to burst, but he was ignored. In 2002, housing advocates in Georgia persuaded Democratic Gov. Roy Barnes and the Legislature to pass an anti-predatory lending law, which made investment banks that created MBSs and investors who bought them liable for financial damage if mortgages turned out to be fraudulent. (When a Republican defeated Barnes later that year, the law was repealed in the wake of a Wall Street lobbying blitz.)

The film ignores these prescient players.

Also missing from “The Big Short” are any of the major decisionmakers – in banking or government – who set (and changed) the rules that made it possible for these get-rich-quick brokers, bankers and investors to game the system.

For example, none of the CEOs of the major banks – Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, Citigroup, Wells Fargo, Lehman Brothers and others – whose lobbying efforts led to the deregulation and whose policies triggered the crash, are depicted in the film.

The film makes a few passing references to Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan – in one scene, he is scheduled to speak at a banking industry conference – but we don’t get to see or hear him. That’s unfortunate, because Greenspan was not only a key player in the unfolding crisis but his views reflected the dominant ideology that bankers, politicians and economists used to justify dismantling decades of government bank regulations.

Like other conservative free-market ideologists, Greenspan – an acolyte of libertarian writer Ayn Rand — believed that government is always the problem, never the solution, and that regulation of private business is misguided.

It wasn’t until the system imploded that Greenspan gained any insight about the fundamental flaw of his belief that greed is the best operating principle for an economic. In 2008, testifying before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, Greenspan admitted: “Those of us who have looked to the self-interest of lending institutions to protect shareholders’ equity, myself included, are in a state of shocked disbelief…. This modern [free market] paradigm held sway for decades. The whole intellectual edifice, however, collapsed in the summer of last year.”

Had the media, government regulators, the rating agencies or Congress done their jobs, the nation could have been spared the widespread suffering caused by the housing crisis and the economic collapse.

By 2010, when journalist Michael Lewis was putting the finishing touches on the book that inspired the film, Americans were starting to get angry about the epidemic of foreclosures and layoffs, the sharp plunge in housing values, and the bailout orchestrated by the George W. Bush administration at the behest of the banking industry and its closest ally in government, Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, a former Goldman Sachs CEO. At the time, few journalists had yet exposed the inner workings of the banking industry that led to the crisis, but most Americans – who knew someone who had lost a home or a job or had to postpone their kids’ college education because they were deeply in debt — understood that something was seriously wrong with the system.

The filmmakers seem to think that the American people learned nothing from the financial crisis. It is no doubt true that, eight years after the housing bubble burst, most Americans can’t explain what a “subprime loan,” “mortgage backed security,” “collateralized debt obligation,” “default swap” or even a ”hedge fund” is. But that doesn’t mean that Americans don’t realize that they were screwed or don’t know whom to blame.

A recent Pew Research Center poll discovered that 60 percent of Americans—including 75 percent of Democrats—believed that “the economic system in this country unfairly favors the wealthy.” A New York Times/CBS survey found that about three-quarters (74 percent) of Americans—including 84 percent of Democrats, 72 percent of independents and 62 percent of Republicans—believe that corporations have too much influence on American life and politics. Seventy-three percent of Americans favor tougher rules for Wall Street financial companies, versus 17 percent who oppose stronger regulation. Fifty-eight percent of Americans said they would support breaking up “big banks like Citigroup.”

* * *

“The Big Short” begins with Lewis Ranieri, a Solomon Brothers banker who invented the idea of packaging home loans into investments called mortgage-backed securities (MBS) in the 1970s. The film then jumps to the mid-2000s, when Michael Burry, played in the movie by Christian Bale, and others realize that the subprime loans behind these MBSs are about to explode.

As a result of this time-lapse, the film ignores the root of the crisis, which began in the 1980s, when the banking lobby used its political clout — especially campaign contributions — to get the Reagan administration and Congress to loosen restrictions on the kinds of loans they could make. In 1999, Congress (with the support of President Bill Clinton) repealed the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act that had imposed a regulatory separation between traditional banking and higher-risk investing activities. In doing so, they tore down the last remaining legal barriers to combining savings-and-loans, commercial banks, investment banks and insurance companies under one corporate roof. They soon became part of a giant “financial services” industry.

Washington walked away from its responsibility to protect consumers with regulations and enforcement. While most federal regulators looked the other way, banks and private mortgage companies indulged in risky loans and speculative investments. (In one scene in “The Big Short,” a staffer for the Securities and Exchange Commission explains that the agency lacks the staff to police the industry for fraud and abuse.) Under these conditions, new players emerged to exploit the opportunities to make a fast buck. They invented new “loan products”– such as subprime loans and adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) –that put borrowers at risk.

With interest rates low, housing prices on a steady rise, and little government regulation, a new breed of lender — mortgage finance companies — devised high-interest, high-fee schemes to entice families to take out loans that traditional savings banks would not make. Companies like Household Finance and Countrywide Financial grew quickly, making extraordinary profits through unsavory means, bending the rules and lowering normal banking standards. Major banks – like Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs and Bank of America – provided the credit these finance companies needed to keep pumping out loans.

The lenders used mortgage brokers to bring in the business. These street hustlers of the lending world often used mail solicitations and ads that shouted, “Bad Credit? No Problem!” “Zero Percent Down Payment!” to find people who were closed out of homeownership, or homeowners who could be talked into refinancing. They seduced millions of people into signing on the dotted line. They targeted minority and low-income urban areas – many of which had been starved for credit for years by mortgage discrimination (called “redlining) – for these predatory loans.

The major ratings agencies – Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s – put their stamp of approval on these MBSs with AAA ratings without bothering to find out if the underlying loans were sound. There’s a great scene in “The Big Short” where an S&P staffer reluctantly admits that it wasn’t in the company’s interest to find out. If they gave these MBSs bad ratings, the banks would take their business to the competition.

The subprime lenders didn’t hold on to these loans. Instead, they sold them — and the risk — to investment banks and investors who considered these high interest rate, subprime loans a goldmine. By 2007, the subprime business had become a $1.5 trillion global market for investors seeking high returns.

The whole scheme worked as long as borrowers made their monthly mortgage payments. But as mortgage premiums grew while incomes stagnated, the scheme became a house of cards. When borrowers couldn’t or wouldn’t keep up the payments on these high-interest loans, what looked like a bonanza for everyone turned into a national foreclosure crisis and an international economic meltdown. Some of the investors, like pension funds, destroyed the savings of millions of Americans.

* * *

Every aspect of the financial industry was so short-sighted and greedy that they didn’t see the train wreck coming around the corner. But “The Big Short” isn’t really about them. Instead, it focuses on the few people who figured out that the whole banking system was a house of cards and that the bubble was going to burst. The film’s key characters are based on real people, although, except for Michael Burry, it uses different names. They were as greedy as the other bankers but because they were social misfits, outsiders or cynics, they could see what the insiders were unable or unwilling to recognize. So we get to see the banking system through their eyes. Or, in the case of Burry, his one eye.

Burry founded Scion Capital LLC, a hedge fund he operated from 2000 until 2008. An eccentric former physician with Asperger’s syndrome and few social skills but with a remarkable capacity for reading obscure financial statements, we see Burry walking barefoot in his office, air drumming with wooden drumsticks while listening to music through headphones, and bouncing a tennis ball at the same time he’s looking at a computer screen filled with numbers about mortgages. In 2005, Burry was one of the first investors to recognize the financial sector’s flimsy foundation and accurately predict that it would collapse two years later.

With this new insight, Burry and a handful of others invented a new tool of their own – the credit default swap — to exploit the system and get rich. Like Max Bialystok and Leo Bloom in Mel Brooks’ film “The Producers,” who realized they could make more money if they could entice investors to back a Broadway play that would quickly fail, they bet against the system. The default swap is essentially an insurance policy on the mortgage bonds. If the bonds failed, they’d collect big bucks.

But first they had to persuade banks to lend them the money to buy the insurance. Believing that the housing system was invulnerable, they gladly gave them the money, figuring—like most insurance companies – that they’d never have to pay. When the market collapses just as Burry predicted, he makes a 489 percent profit for himself and his investors. The film is partly an ode to the outsiders for having the courage and resourcefulness to think outside the box, even though they were just as avaricious as the other bankers.

But the most compelling scenes in the movie – the ones that help us understand how the banks were exploiting real people — take place in Florida, where Mark Baum (a hedge fund manager based on Steve Eisman and brilliantly played by Steve Carell) goes to investigate whether the banking industry’s view of the fundamental soundness of the housing market is accurate. He talks with two mortgage brokers who giddily explain how banks pay them higher fees if they can entice borrowers into risky adjustable-rate mortgages instead of conventional loans. The brokers call these customers NINJAs (no income, no job) because the banks don’t want to know if they can afford the loans. One of the brokers, a former bartender, may not know – and doesn’t seem to care to know — that the banks will quickly resell them to investors as part of mortgage-backed securities. After hearing the brokers brag about their own success in getting clueless borrowers to buy homes they can’t afford, Baum asks one of his employees, “Why are they confessing?” The answer: “They’re not confessing, they’re bragging.” Thanks to this encounter, Baum understands that the MBSs backed by these mortgages are really junk bonds that will ultimately be worthless.

Baum knocks on the door of a house, where a large working-class man tells him that he’s renting the home. When Baum informs him that the homeowner – whom the man calls his landlord — hasn’t paid the mortgage for months, the man explains that he’s been paying his rent on a regular basis. “Does this mean I’m going to get evicted?” he asks Baum. (At the end of the film, we see that the man and his family are now living in a car).

A Florida real estate agent takes Baum and his associates on a tour of a neighborhood with lots of large newly built homes that are vacant and have “for sale” signs in the front yard. She explains that lots of the owners have lost their jobs, but she thinks this is just a temporary setback. She is too naive to realize that what she’s seeing is the housing bubble starting to burst.

Baum was shocked by what he learned in Florida, recognizing that it could mean the collapse of the entire economy. A few others came to the same realization. Two eager young investors — Charlie Geller (John Magaro) and Jamie Shipley (Finn Wittrock) – enlist the help of retired banker Ben Rickert (Brad Pitt) to raise the money they need to make a killing with default swaps. But they also visit their former college buddy who is working as a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, hoping he’ll expose the scandal. The reporter wasn’t sure he believed their claims but even if he did, he told them, he couldn’t write a story about it. Doing so would jeopardize the trust of the industry sources he needed to do his job. This one scene serves as a proxy for the media’s failure to uncover or report on the financial crisis until it was too late.

* * *

As Burry, Baum, and the others predicted, the whole system came crashing down in 2007. The fight over banking reform in Congress was the first battleground in what has become an ongoing war. President Obama inherited the collapsing economy, and the federal bank bailout, from George W. Bush. Feeling the mounting anger, the Obama administration’s response to the crisis was to push for stronger regulations on the financial industry, which ultimately led to the Dodd-Frank legislation. The financial industry lobby used its substantial political clout to water down many of its strongest components. The new law, which Obama signed on July 21, 2010, focused primarily on protecting consumers from abusive practices. It also dealt with the concern that some banks were “too big to fail.” Dodd-Frank requires the biggest banks to develop resolution plans (“living wills”) demonstrating their ability, if necessary, to go out of business in an orderly fashion that will not lead to major economic fallout. The law requires federal regulators to order the restructuring, or even the breakup, of any megabank that fails to produce a credible resolution plan. The legislation was much weaker than what most advocacy groups had hoped for, especially when it came to regulating derivatives, but was still the most significant change to financial regulation since the Great Depression.

This battle catapulted Elizabeth Warren, an obscure Harvard Law professor, onto center stage as a relentless advocate for regulations on the financial services industry. Several years before the financial crash, the Democrats in Congress asked her to draft legislation to reform federal bankruptcy law, but she was thwarted by the bank industry lobby. Her next assignment was as Congress’ official monitor of the federal bank bailout program. There, too, she met resistance not only from the banks but also from Obama’s Treasury secretary, Tim Geithner, a former banker. She became better known to the public in 2010 as the creator and leading champion for a Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. With Obama’s support, and over the strong opposition of the banking industry, she successfully got the agency into the Dodd-Frank bill. Obama refused to appoint her to run the bureau, believing that her nomination would be too controversial, so instead she ran for the U.S. Senate seat from Massachusetts against Republican Scott Brown, who had replaced Ted Kennedy after his death in 2009. Warren’s 2013 victory showed that the banking industry was not invincible. She has since become the nation’s most forceful critic of Wall Street and of the failure of Congress and federal regulators to hold banks accountable for their misdeeds. Last year, Warren slammed Attorney General Eric Holder and bank regulators for failing to investigate and prosecute banks, asking whether they viewed large Wall Street banks as “too big to jail.” “The message to every Wall Street banker is loud and clear,” said Warren at a Senate Banking Committee hearing in 2014. “If you break the law, you are not going to jail, but you might end up with a bigger paycheck.” Her populism has made her a political celebrity.

The film also ignores the next upsurge of protest in the battle against banks. In 2010, as the foreclosure epidemic worsened, several community organizing groups and unions came together to pressure banks and the Obama administration to do more to save families from losing their homes. They mounted protests at bank headquarters around the country, generating media attention. Obama’s hands were tied by the Republican Congress, but these protests helped Attorneys General Eric Schneiderman of New York and Kamala Harris of California push for a stronger national settlement with banks over foreclosure relief. Then, in September 2011, a handful of activists took over Zuccotti Park in New York City to draw attention to the nation’s widening wealth and income gap. The Occupy Wall Street movement quickly spread to cities and towns around the country, changing the national conversation. At kitchen tables, in coffee shops, in offices and factories, and in newsrooms, Americans began talking about economic inequality, corporate greed, and how America’s banks and super-rich damaged our economy and our democracy. Occupy Wall Street provided Americans with a language — the “1 percent” and the “99 percent” — to explain the nation’s widening economic divide, the undue political influence of the super-rich, and the damage triggered by Wall Street’s reckless behavior that crashed the economy and caused enormous suffering and hardship.

Even many Americans who did not agree with Occupy Wall Street’s tactics or rhetoric nevertheless shared its indignation at outrageous corporate profits, widening inequality and excessive executive compensation side-by-side with the epidemic of layoffs and foreclosures, as reflected in the public opinion polls mentioned earlier. Its ongoing influence can be seen in growing media coverage of economic inequality, hardship, insecurity and poverty, and more vigilant coverage of the banking industry.

It can also been seen in the efforts of politicians to seize the new mood. In a December 2011 speech in Osawatomie, Kansas, for example, Obama sought to channel the growing populist outrage unleashed by the Occupy movement. He criticized the “breathtaking greed” that has led to widening income divide. “This isn’t about class warfare,” he said. “This is about the nation’s welfare.” Obama noted that the average income of the top 1 percent has increased by more than 250 percent, to $1.2 million a year. He returned to these themes in his Jan. 24, 2012, State of the Union address. He called on Congress to raise taxes on millionaires. “Now, you can call this class warfare all you want,” he said, adding, “Most Americans would call that common sense.” Even some Republicans running for president and Senate in 2012 voiced their concerns about widening inequality and “crony capitalism.”

Years after local officials pushed Occupy protesters out of parks and public spaces, the movement’s excitement has been harnessed by community organizers and unions. Bank employees (such as tellers, secretaries and call center workers) have joined forces with the Communication Workers of America and community groups (including Jobs with Justice and the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment) to give them a voice in their workplace. In October, hundreds of bank workers and their supporters, calling themselves the Committee for Better Banks, occupied the lobbies of Wells Fargo and Bank of America branches in downtown Los Angeles. They spoke out not only about low pay but also banks’ high-pressure sales goals that led to discriminatory lending practices.

Last year, the city of Los Angeles sued Wells Fargo for unlawful and fraudulent conduct, claiming that rigid sales quotas pressured its employees to engage “in unfair, unlawful and fraudulent conduct.” In September, the city of Oakland, California, sued Wells Fargo in federal court to recover damages caused by the bank’s widespread predatory and discriminatory lending practices. A network of activists called Hedgeclippers has been waging a campaign to expose the political influence troublesome practices of hedge funds around pension funds, college endowments, tax avoidance and climate change.

This takes us to the current contest for the White House. Among the Democratic candidates, Sen. Bernie Sanders has taken up the mantle of Occupy Wall Street, pledging to strengthen federal regulations on the financial industry, restore the Glass-Steagall law that once put strict limits on banking practices, and break up the biggest banks. “To those on Wall Street who may be listening today, let me be very clear,” he said in a recent speech. “Greed is not good. In fact, the greed of Wall Street and corporate America is destroying the fabric of our nation. And, here is a New Year’s Resolution that I will keep if elected president. If you do not end your greed, we will end it for you.” Sanders’ proposals have pushed Hillary Clinton to announce her own plan to hold Wall Street accountable. She has insisted that her close ties to, and campaign donations from, the industry will not impede her ability or willingness to reform Wall Street.

Paul Sperry, a fellow at the conservative Hoover Institution, recently penned a column in Rupert Murdoch’s New York Post calling “The Big Short” “a two-hour political campaign ad for Sanders.” Sperry is legally wrong but politically on target. The film certainly echoes the themes that Occupy Wall Street, Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have been using to explain that the housing collapse and the economic crisis were not inevitable but resulted from choices make by powerful business and political figures obsessed with profits and power. The film could have gone further and pointed out that the system can be fixed, but that it will take a bold and persistent grass-roots movement to elect candidates and pressure politicians to enact the laws needed to stop Wall Street’s excesses.

Peter Dreier is E.P. Clapp Distinguished Professor of Politics and chair of the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College. His most recent book is “The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame” (Nation Books).