The social contract is a modern invention. It is the implicit agreement between a state and its people about how a country should be governed. When the social contract works, there is peace in the land. Think of John F. Kennedy’s ringing words: “A rising tide lifts all boats.”

But when the social contract breaks down, as it seems to be today, people get restless. If the broken contract is not fixed, there will be revolt or even revolution. We’re seeing inklings of that in the presidential election.

It was Thomas Hobbes, in 1655, who first proposed a social contract. Hobbes had lived through the English Civil War—what he called a “war of all against all.” He wanted to avoid such destructive debacles. His plan?

People would give up liberties in exchange for security provided by government—Leviathan. Hobbes’ genius was to remove religion from governance: no more “divine right of kings.” It was the first formula for a modern secular state.

A generation later, John Locke worried that the rabble democratic spawn of the same civil war might come after the wealth of his propertied class. So in 1688 he came up with a different social contract. People would give up liberties in exchange for protection of private property.

Locke’s social contract promised two things: “life, liberty, and private property,” and “consent of the governed.” Thomas Jefferson plagiarized and bastardized Locke’s language to write the Declaration of Independence. As a polity, we are conceptual children of Locke’s.

FDR borrowed his social contract from Otto von Bismarck. The collapse of capitalism in the Great Depression required radical measures. As Bismarck had done to inoculate Germany from socialism in the 1880s, FDR delivered a basic safety net in the 1930s.

Social Security, unemployment insurance and other such programs helped deflect demands for even more extreme socialist reforms. The capitalists hated Roosevelt but he saved capitalism from its own self-inflicted near-suicide.

After World War II the U.S. entered into yet another social contract: Everybody would share in the fruits of an expanding economy. That’s what Kennedy’s “rising tide lifting all boats” metaphor was about. It worked, brilliantly.

The decades from 1950 to 1970 delivered the most buoyant, widely shared economic growth in American history. It truly was the “golden age” of American capitalism.

But shared prosperity is no longer the operative social contract. Ronald Reagan began dismantling it in 1981 when he transferred vast amounts of national income and wealth to the already rich. He called it “supply side economics.”

Supposedly, the rich would plow their even greater riches back into the economy, which would magically return that wealth—and more—to everyone else. George H.W. Bush called it “voodoo economics.” It seemed too good to be true. It was. Consider the facts.

Since the late 1970s, labor productivity in the U.S. has risen 259 percent. If the fruits of that productivity had been distributed according to the post-World War II shared prosperity social contract the average person’s income would be more than double what it is today. The actual change?

Median income adjusted for inflation is lower today than it was in 1974. A staggering 40 percent of all Americans now make less than the 1968 minimum wage, adjusted for inflation. Median middle-class wealth is plummeting. It is now 36 percent below what it was in 2000.

Where did all the money go? It went exactly where Reagan intended.

Twenty-five years ago, the top 1 percent of income earners pulled in 12 percent of the nation’s income. Today they get twice that, 25 percent. And it’s accelerating. Between 2009 and 2012, 95 percent of all new income went to the top 1 percent.

This is the exact opposite of shared prosperity. It is imposed penury. That is the new deal. Or more precisely, the new New Deal, the new social contract.

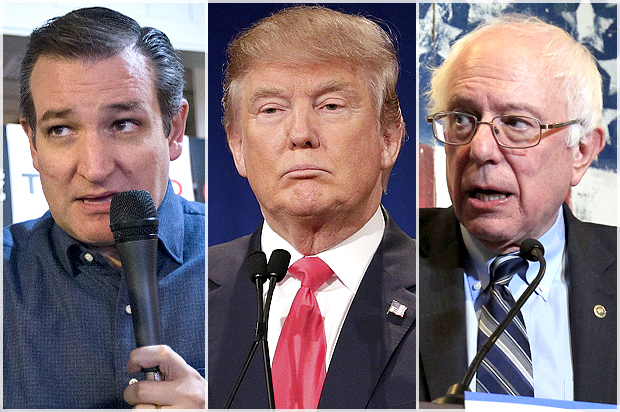

This is what is behind the success of Ted Cruz, Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, the effective winners in Iowa. They are all anti-establishment candidates riding a tidal wave of domestic discontent.

Their audiences, on both the right and the left, are downwardly mobile former middle- and working-class people, those for whom the old social contract has been rescinded and on whom the new one has been imposed—without their consent.

The appeal of these anti-establishment champions signals that this is not a shallow or partisan issue. It is a deep and broad-based social grievance, a demand for fundamental change: a revision to the surreptitiously imposed new social contract.

The candidate who articulates that best will be his or her party’s nominee. The candidate in the general election who can then pull the other party’s voters across the aisle in pursuit of this cause will be the winner in November.

It is unlikely Hillary will pull many Republicans away from whomever the Republicans nominate. She is both an object of visceral hatred to most Republicans and the establishment candidate in a year of anti-establishmentism.

Sanders, on the other hand, pulls well from disaffected Republicans. He has little of Hillary’s baggage and polls much better against either Trump or Cruz than does Hillary. He is anti-establishment in a year of fervid anti-establishmentism, a fiery mouthpiece for the intense cross-partisan anger roiling the electorate.

If Sanders can survive the primaries he has a much greater chance of beating any Republican challenger than does Hillary. Whether he can implement his vision of a retrofitted social contract is another matter.

Robert Freeman is the author of The Best One-Hour History series, which includes “The English Civil War,” “World War I,” “The Vietnam War” and other titles.