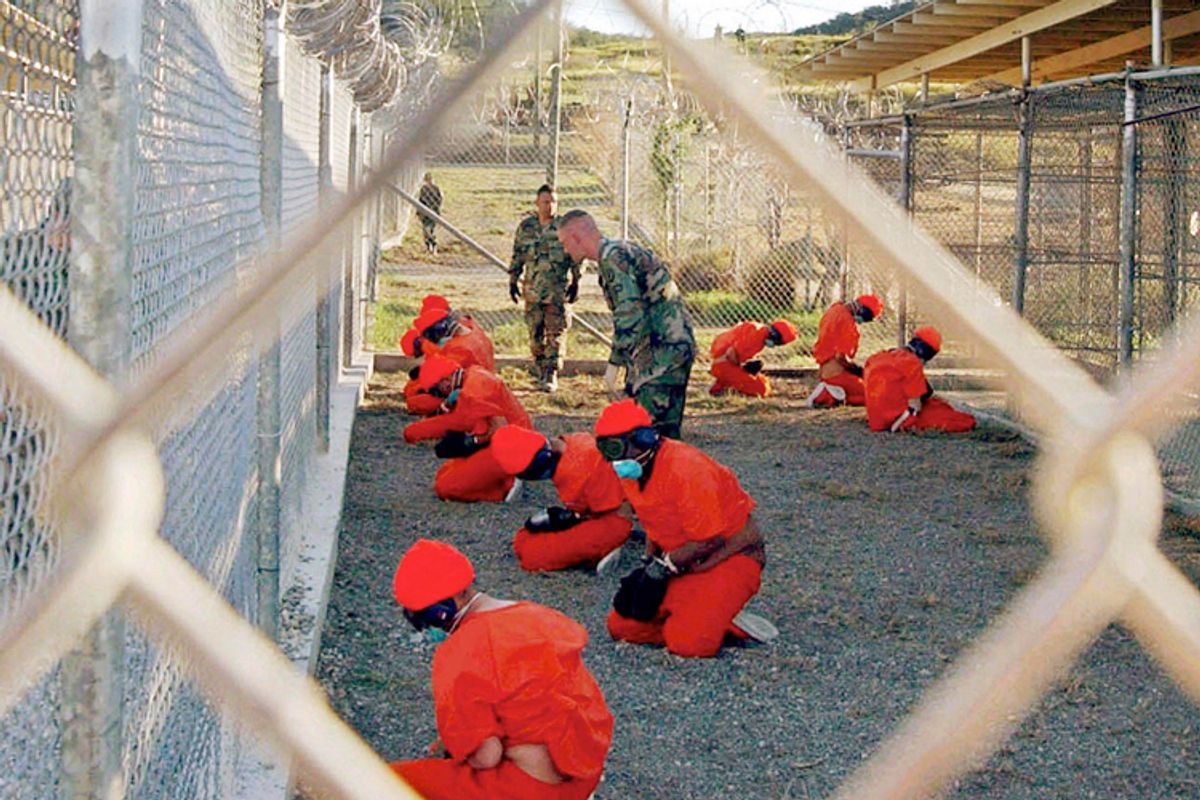

President Obama has just announced his plan to shutter Guantánamo, sending many of the remaining detainees to third countries and others to federal, state and military prisons in the United States.

Closure of Guantánamo means tremendous cost savings to the United States. American taxpayers are now paying $399 million to house approximately 2,000 guards and other staff, which amounts to about 18 personnel for each of the remaining 91 detainees. It also fulfills Obama’s long-standing pledge to close a facility that has become a symbol of torture, one that has harmed American credibility in the international community.

But what are the social implications of closing Guantánamo?

Our research into the experiences of former Guantánamo detainees—including interviews with 78 detainees who were released after years of detention—suggests we need to be thinking not just about how to close Guantánamo, but about what happens after Guantánamo. What we choose to do next will have long-term human rights and security ramifications that—at least in terms of the public discussion—have largely been ignored.

According to our research, we found many former detainees were highly stigmatized and unable to obtain jobs and reintegrate into their communities. As one former detainee put it: “I was living in hell before Guantánamo, and I was living in hell in Guantánamo, and when I returned home, it was another hell.” Another detainee said his old friends “were afraid of greeting me because they feared they would also be taken into custody or interrogated.”

Several former detainees returned home to discover that family members had died or disappeared and that their citizenship was stripped away. Others found that their homes had been bartered to facilitate their return. They said government and non-government organizations ignored their pleas for help when the private sector refused to employ them.

One said he could never return home because of the likelihood that he would face imprisonment and execution. He told us that when he talked to his children on the phone, they treated him like a stranger. He didn’t like going outside because he saw couples holding hands or walking with their children, and it reminded him of what he had lost forever.

As many as 94 percent of the men housed at Guantánamo should never have been there as they were never a serious security risk to the United States. Many were swept up by the Bush administration’s bounty program offering cash awards leading to the capture of suspected terrorists. The bounty program created large fiscal incentives for locals, particularly along the Afghan-Pakistani border, to turn over individuals who had no connection to terrorism. As cash payments circulated, local militia and village leaders began seizing strangers passing through the countryside to whom the bounty-collector had no loyalty, or neighbors who possessed coveted land. A lack of sufficient battleground screening meant many detainees got passed along to Guantánamo when they shouldn’t have. A blanket policy of “no release”—and a lack of a plan for what to do with them when home countries wouldn’t take them back or we couldn’t send them back—meant that they continued to be housed even after this issue was discovered.

According to our research, most former detainees, when asked, didn’t resent America in the immediate aftermath of their release. “Everyone makes mistakes,” said one man who was let go after several years of detention. But how former detainees have been treated since impacts their perceptions of America, their home countries and the countries in which they’ve ended up.

Many would like the U.S. to clear their name by admitting that they should never have been in Guantánamo in the first place. This desire is held both by former detainees who have been returned to their home countries and those who have been released elsewhere.

Several former detainees explained how “the mark of Guantánamo” continues to stain their future prospects: “Something should happen to the people who are responsible for arresting all these people and then releasing them back, and not really clearing their names…. If they’re going to charge detainees, they should charge them. It doesn’t take [years and years] to convict someone of a crime. … [To] just leave them there [at Guantánamo] and say to the world, these people are terrorists based on what, we don’t know, is just ridiculous.”

In addition to the social and structural difficulties former detainees have encountered, many also appear to suffer from psychological trauma, which negatively impacts their ability to make social connections and resume a baseline of normal social functioning. Post-release, many former detainees have struggled to negotiate new identities and regain hope for the future.

Right now, as we take first steps toward finally closing Guantánamo, we have a choice: Do we continue to transfer individuals with little to no social, economic or psychological support, leaving them desperate for a productive future? Or do we make a relatively tiny investment in their future to set them on a path toward productivity?

Even as Guantánamo finally and rightfully closes, the damage endures—as does our responsibility.

Eric Stover and Alexa Koenig, with Berkeley Law’s Laurel Fletcher, are authors of “The Guantánamo Effect: Exposing the Consequences of U.S. Detention and Interrogation Practices” (University of California Press). Stover, faculty director of the Human Rights Center at Berkeley Law, and Koenig, executive director of the Human Rights Center and former program manager for the Witness to Guantánamo Project, along with Arizona State professor Victor Peskin, are also authors of the forthcoming “Hiding in Plain Sight: The Pursuit of War Criminals from Nuremberg to the War on Terror” (University of California Press).

Shares