Unrestrained language. Simplistic, fear-based messages. Expressions of personal contempt. Childish tit-for tat. Our democracy has countenanced, if not sanctioned, incivility ever since Alexander Hamilton unwisely insulted one particularly sharp-eyed political opponent, and that man, the ordinarily patient Aaron Burr, privately observed of the sharp-tongued Hamilton to a trusted friend: “He has a peculiar talent of saying things improper and offensive.”

In those days, insults during campaign season were handled directly, and out of the public view––with sometimes deadly results. Newspapers reported “affairs of honor” like the Burr-Hamilton duel, of course, but those papers would find a loyal readership with or without the sensationalization of partisan attacks. The difference these days lies in the power of the visual over newsprint, and in the high-stakes competition among media corporations: Incivility is pretty much all that attracts viewers (and advertisers) to the televised debates. Raised voices pretty much govern our national elections.

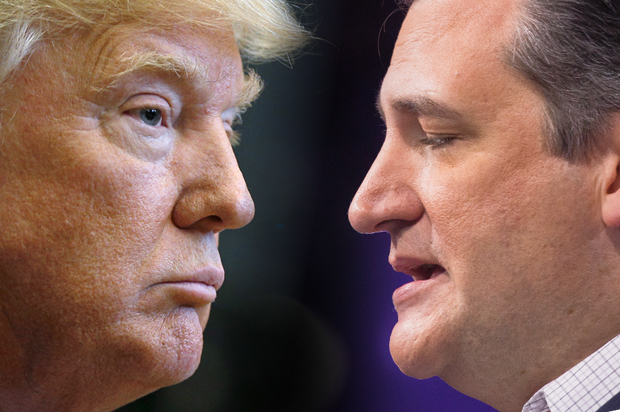

Under these conditions, no one can be surprised by the personalities who have emerged from their respective corners to engage in verbal fisticuffs. Soft-spoken Ben Carson and the unnatural, “low-energy” debater Jeb Bush were not made for such an environment. We get it. Strident-sounding men (not to exclude the similarly cast Carly Fiorina) with strong egos and financial backing who imagine themselves worthy leaders will run for president whether or not their public record actually serves the public. Donald Trump is a real estate man whose scatter-shot investments are not all smart but who admits to no bad ideas. Ted Cruz owns a Senate record that bespeaks a rude, divisive, uncompromising demagoguery. What the two men have in common, besides a sturdy belief in the value of their Ivy League credentials, is that they are self-promoting performers who love to hear themselves speak. Notably, too, both lack an off-switch.

They are, in meaningful ways, the latter-day incarnations of two colorful southern politicians: the Virginian John Randolph and the Mississippian James Vardaman. Randolph of Roanoke, as he was known, was a cranky, oddly shaped slave owner, who for the first three decades of the nineteenth century translated his small-government principles into an unreserved language few understood. Though six feet tall, his shoulders spanned only thirteen inches. His dress was old-style: he was known to attend Congress in his riding outfit, attended by a servant who passed him a flask on command. He was erratic, garrulous, clownish, folksy, a knight errant who had no filter when he spoke. He accused opposing politicians of corruption. Occasionally, his barbs were beautiful: “There is a corruption of timidity, which consists in men not saying what they think.” (We might learn from that.) As he rambled on for literally hours on the floor of Congress, Randolph acknowledged himself “a wild man,” as transcribers scurried to keep up with his verbose meanderings, and newspapers across the states regularly carried page-long excerpts. Words were his dancing partners: even when detouring from the subject at hand, which was nearly always, he kept his colleagues riveted.

The Ivy-educated debater peppered his speeches with Latin and Greek aphorisms and Biblical allegories, filling the air with eyebrow-raising non-sequiturs. The impractical scene-stealer invited opponents to mock what he could not change about himself: his beardless face, his sexual ambiguity (we don’t know the size of his hands). To his constituents, it didn’t matter whether they even understood him: they loved it that he thumbed his nose at the establishment. As a wealthy plantation owner he was of the elite; but as a thorn in the side of all the “regular politicians,” he was of the people.

One day in 1826, in the Capitol, Randolph went a tad too far, calling the relationship between President John Quincy Adams and Secretary of State Henry Clay unseemly––without exactly naming names. He dubbed them “the puritan and the black-leg”––the latter meant “cheater.” Clay found out; he went ballistic––“Your unprovoked attack of my character in the Senate of the United States….”––and he challenged Randolph to a duel. So a cabinet member and a U.S. senator, in the manner of Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton, took to the field of honor. Both missed on the first fire, and Clay said: “This is child’s play!” before demanding another go. “Mr. Clay, you owe me a coat,” the hubristic oddball Randolph said to the man whose manly honor was hereby (symbolically) restored after his second bullet passed through the Virginian’s coat without striking flesh. This legendary encounter made all the papers. Thirty years later, in the Senate chamber, it was the brutal caning of abolitionist Charles Sumner, rendered unconscious by a South Carolina congressman, that preceded the Civil War. In antebellum America, people still believed, sometimes in perverse ways, that “actions speak louder than words.”

The point is that in nineteenth-century political theater, hurled insults invited physical consequences. Once the code duello no longer prevailed in American politics, political combat on the national stage was resolved (or left unresolved) with more talking. In the first decade of the twentieth century, Governor Vardaman of Mississippi was a caricature of southern discomfort. “The White Chief,” as many knew him, was the darling of angry poor whites, combining a cruel racist bent with a redneck proclivity for trash-talking. So when Theodore Roosevelt received Booker T. Washington at the White House and dined with the African-American leader, Vardaman went nuts, calling the president a “coon-flavored miscegenationist.” Questioning Roosevelt’s pedigree, he reported that the president’s mother, while pregnant, was frightened by a dog; and in a moment of alchemy, the “qualities of the male pup” were transferred to the embryo. This kind of personal inventive was Vardaman’s stock in trade; he had no respect for the office of president. As with Trump, all that mattered was bringing down the high and mighty and obliging them to roll in the mud.

The rabble-rousing racist Vardaman insisted that white tax dollars should only go to support of white schools. He didn’t care how it sounded. Everywhere he went at election time, he posed alongside symbols of “lowdown” white culture and appealed to the basest instincts he could bring out in the uneducated whites who flocked to him. He raised crowds that loved his mudslinging, as he delivered an early version of the Trump message: “I love the poorly educated.”

The American blowhard politician of today has Secret Service bodyguards, while imagining himself a moral warrior: part George Washington, part Dirty Harry. “I’m gonna destroy ISIS” are fighting words, to be sure, but they’re mere words coming from someone whose limousine lifestyle belies his threatening rhetoric. From a swollen head comes: “I know words. I have the best words.” That was Trump’s empty boast, of course, weighing even less than Ted Cruz’s empty recitation of Dr. Seuss. Trump’s radioactive oratory is more children’s literature than formulated policy; and it’s a children’s book that teaches children to push other children around. “He couldn’t be elected dogcatcher,” Trump says of Marco Rubio. On himself, generically: “I have great relationships with people.”

Advertisers of consumer products or consumer candidates engage in “branding.” A brand is one choice among manufactured choices. How sad it is when political personalities are differentiated not by specific positions taken so much as by the impassioned performances they give to the crowds they attract. The eccentric politician in the Randolph/Vardaman mold targeted a niche market; he sought to entertain a select constituency, and that was enough. He did not expect to become president. In part, this is because Randolph and Vardaman existed in a world of print. Today, the danger to democracy is magnified, because TV and the Internet communicate live images and let us picture roaring crowds. The obnoxious entertainer exploits a more malleable, manipulable medium, aided by expensive teams of media strategists, supported by dedicated pollsters.

From the anger-fueled Trump campaign we learn that the act of degrading others scores political points. Trump and Cruz, like Randolph and Vardaman, feed their crowds fake formulas for security. What’s different now is the appeal beyond the South. Still, what Randolph, Vardaman, Trump, and Cruz all have in common is that they were/are smug and imperious as they lecture to crowds. Even when they pretend to be loving Christians, they’re hostile, heedless men, rallying the troops with a tone-deaf abandon. They are generals whose army fights internal enemies that do not really exist. They want their country back. They want America to be great again. They deploy every cliché in their playbook until they find the one that works on you.

Must this be the future of American democracy? Randolph of Roanoke started the politician-as-entertainer trend. He was a conservative Don Quixote who fought for an undefinable “purity,” and he soothed more than a few troubled souls whose mortal fears matched his own. But he knew and admitted where his power over others ended. He looks tame now. Vardaman stood for a politics of angry mockery, and was thus a nearer kin to the orgiastic gatherings of Trump and Cruz supporters, who symbolize the sinister triumph of aggressive unpleasantness and measureless disaffection.

Trump confines himself to few simple––“great”––words. He rails: “Other countries treat us as very, very stupid babies.” It’s not words that he’s selling: it’s the strength symbolized by a tall building that bears his name or the gaudy gold standard that caresses and envelops him. Because Trump steaks are the meat choice of strong men.

Cruz, on the other hand, is symbol-less. His only “brand” is the faux-earnest conservative word salad: “Imagine millions of courageous conservatives, all across America, rising up together to say in unison, ‘We demand our liberty.’” That was Ted when he announced for the presidency. “Imagine abolishing the IRS!” “Imagine a government that believes in the sanctity of marriage!” Cruz stokes the fires of all who can be convinced that government is the enemy. And that’s really all he’s selling: “The stakes in this country have never been higher … our country is at a crisis point … We have a corrupt and broken system…. Liberty is under assault.”

Trump and Cruz are salesmen whose product, when all is said and done, is the pet rock. Remember that one? Back in the ’70s, it came slickly packaged in a cardboard box with holes for ventilation to insure that the “pet” was still breathing when it arrived at your door. Inside the box was a studious manual that covered care and use. But in the end, it was still just a rock.

Up until this past year, Republicans were vowing to become “the party of ideas” again. In 2016, they have obviously stopped trying.