Thirty years ago, during my second year of teaching humanities at the Philadelphia College of Performing Arts (1985-86), I created an elective two-semester course called “Lyric” that began with ancient Greek poetry and ended with modern song lyrics, from Broadway musicals to folk-rock. In the course catalog, I described it as “a study of how contemporary song lyrics developed from the tradition of lyric poetry and folk ballads.” My aim was to demonstrate how poetry had begun as ritual performance, accompanied on the lyre, and how after a half-millennium of the Gutenberg print era, poetry had returned to its performance roots and its spiritual bonding with music.

My immediate target was our music majors in both the classical and jazz programs. Many young guitarists and drummers were playing in bar bands and trying to develop their own material, in hopes of landing a record contract. The writing requirement for the course was “critical or creative,” with the option to compose original song lyrics. The second semester, which covered Romanticism to modernism, had a natural organic shape, because Lyrical Ballads, the revolutionary 1798 volume of poems by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, was partly inspired by the new interest in folk culture typified by Robert Burns’ collecting of rural Scottish ballads.

I was concerned about the declining quality and prestige of popular song lyrics in the 1980s, when visual flash, tailored to the exciting new genre of music videos, was increasingly dominating music-industry priorities. In hard rock, flamboyant virtuoso guitar solos were replacing the marriage of vivid lyrics with expressive vocals. Working with aspiring songwriters, I found that exposure to major poetry sharpened their awareness of the power and possibilities of language. Simple strategies--such as typing up their own lyrics-in-process to peruse visually—helped them clarify basic issues of theme and form and detect any inconsistencies in point of view.

After a merger in 1987 with our next-door neighbor, the Philadelphia College of Art, to form the University of the Arts, “Lyric” evolved into its present one-semester incarnation, “The Art of Song Lyric,” a course of general cultural appreciation for students from all majors. As my coverage of music history expanded, poetry per se was dropped for reasons of time, and the creative writing component was also discontinued. Term papers now focused on popular, jazz, or art song in any time period or world region. Frequent topics remain leading lyricists and vocalists, past or present, as well as musical groups, famous or not. For example, I have periodically gotten intriguing papers about struggling club bands in metropolitan Philadelphia and New Jersey.

My classroom procedure remains the same: I distribute lyric sheets of selected songs, and we methodically analyze them like poems, with close attention paid to voice, tone, imagery, and narrative (if relevant), with its ancillary premises of character, scene, and time. It is crucial to do my own lyric sheets, because published versions of even classic hit songs are often startlingly inaccurate, with misheard words, jumbled together lines, or missing stanza divisions that obscure a shapely song structure. I play the song twice, before and after our discussion. Ideally, the students on second hearing will experience a sense of pleasurable surprise and revelation, as the song seems to have strangely altered and expanded on its own.

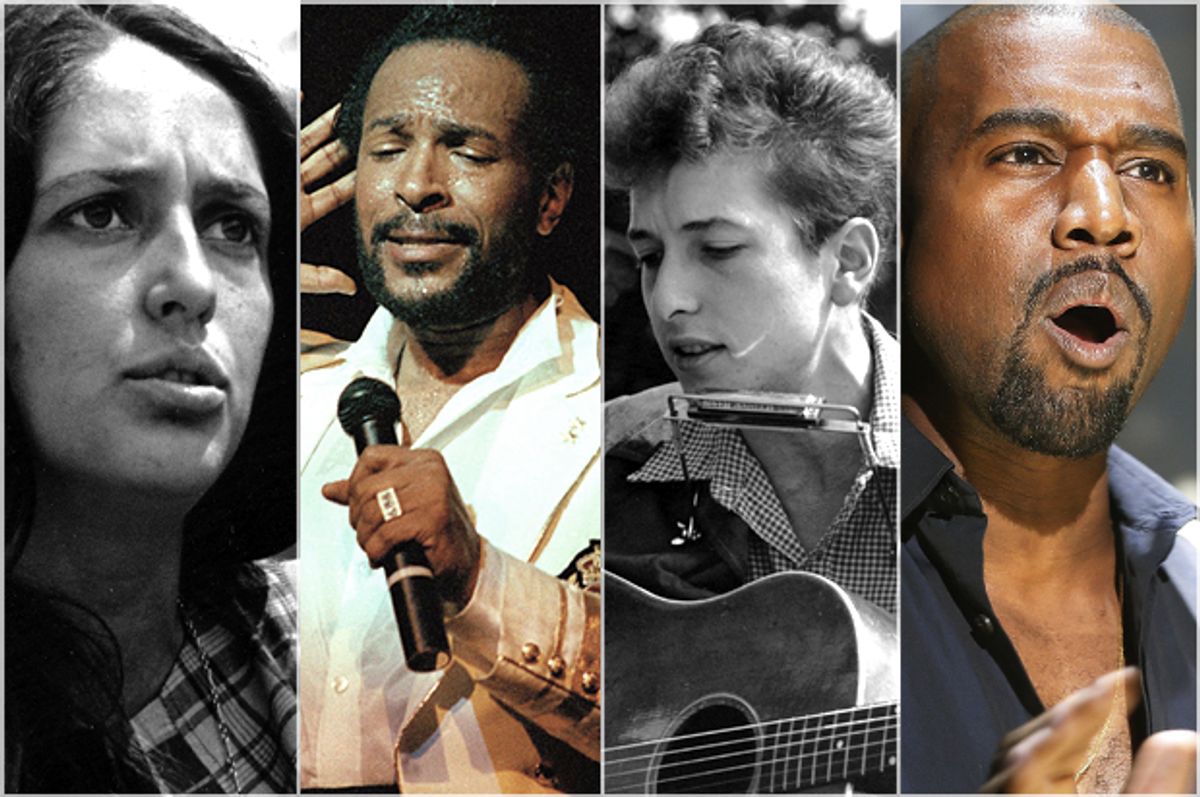

My song choices have steadily changed, but one favorite remains fixed because of its resounding success over the decades: I always begin the semester with “Silver Dagger,” the traditional ballad from the Southern Appalachian Mountains with which Joan Baez opened her blockbuster first album in 1960. The economy and compression of this haunting song, streamlined by generations of oral transmission, should stand as an inspiration to any writer.

Don’t sing love songs, you’ll wake my mother,

She’s sleeping here right by my side,

And in her right hand a silver dagger,

She says that I can’t be your bride.All men are false, says my mother,

They’ll tell you wicked, lovin’ lies,

And the very next evening, they’ll court another,

Leave you alone to pine and sigh.My daddy is a handsome devil,

He’s got a chain five miles long,

And on every link a heart does dangle

Of another maid he’s loved and wronged.Go court another tender maiden

And hope that she will be your wife,

For I have been warned, and I’ve decided

To sleep alone all of my life.

In this brilliant theater of the here and now, a young woman conducts a tense exchange with her serenading suitor through the open window of what may well be a one-room shack. She urgently hushes him; his song is stifled so that hers can begin—a searing elegy for lost hopes. Poverty cancels out impropriety: she is sitting up in bed, next to her sleeping mother, whose steel dagger gleams silver, as if in moonlight. The mother’s tight grip represents her world of fear, her thirst for vengeance, and ultimately her choking of her daughter’s life.

In the British and Scots-Irish ballad tradition, from which today’s country music developed, men are mobile, roaming free while women endlessly wait, abandoned or pinned down by duty. The brooding mother is poisoned with cynicism: “All men are false”; all men lie, seduce, humiliate. The daughter, however, sees her absent, derelict father from an appreciative distance: he’s a “handsome devil”, predatory and amoral but charismatic and irresistible. He collects hearts like scalps. His scattered conquests, still infatuated, are like dazed prisoners in a chain gang. His emblem is the coldly metallic—the chain’s iron links as well as the mother’s fetishistic dagger, portraying the penis as impersonally wounding to women, defined as the “tender” and vulnerable. Gender is inescapably polarized.

The song, just four stanzas long, has a wonderfully lucid design, beginning in the present, jumping backward to sketch in the past, then returning to the present. There is no future--or rather the future is murdered by the mother’s bitterness and her daughter’s renunciation. Torn by pity and loyalty, the daughter chooses her mother’s paralyzed state of endless war, a stubborn mountain feud. The two are self-entombed with suffocating bad memories. There will be no more risky love and thus no children or posterity. Time stops.

Although only 19 when she recorded this debut album, where she accompanies herself on acoustic guitar, Baez already had exquisite vocal phrasing as well as a mastery of poignantly modulated dynamics. Other ballads on the album also work well in the classroom, such as “John Riley,” the homecoming tale of a seafarer so changed by seven harsh years away that he is unrecognized by his faithful betrothed, or “Mary Hamilton,” a complex saga of seduction, infanticide, and execution on the gallows that may descend from a 17th century scandal at a royal court.

While Joan Baez has unfailingly impressed, her colleague and sometime flame Bob Dylan has not. To my dismay, Dylan was a very hard sell in my classes throughout the 1980s. His voice struck many students as thin and grating, while the relentless hyper-verbalism and attack style of his protest songs seemed out of sync with the times. That thankfully changed in the 1990s, probably because of the impact of aggressively political rap, which had become hugely popular among white male teenagers trapped in the blandness and materialism of suburban shopping-mall culture. Dylan’s message-heavy intensity seemed relevant again, a recovered stature happily sustained in the new century.

“Subterranean Homesick Blues,” Dylan’s 1965 breakthrough radio hit, is actually a proto-rap song in the rural “talking blues” tradition. Its delirious barrage of satiric blows at a surveillance society of corrupt authority figures, economic exploitation, and assembly-line institutions speaks directly to our time. I have repeatedly used the song to demonstrate how much can be packed into a very short space (two minutes, twenty seconds).

But Dylan’s true masterpiece, in my view, is “Desolation Row”, the more than 11-minute song that closes Highway 61 Revisited (1965). I submit that this lyric is the most important poem in English since Allen Ginsberg’s Howl (which influenced it) and that it is far greater than anything produced since then by the official poets canonized by the American or British critical establishment. The epic ambition, daring scenarios, and emotionally compelling detail of “Desolation Row” make John Ashbery’s multiple prize-winning Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (1975) look like the verbose, affected academic exercise that it is. I have written elsewhere (in regard to the selection process for my book on poetry, Break, Blow, Burn) of my rejection of the pretentious pseudo-philosophizing of overpraised contemporary poets like Harvard’s Jorie Graham, none of whom come anywhere near the high artistic rank of Bob Dylan.

“Desolation Row” is so long—four printed pages taking three class days to discuss—that I rarely do it now. But it is a stunning achievement, with all the passion and vision missing from today’s writers in virtually every genre. When I first transcribed the song for classroom use, its elegantly symmetrical structure leapt into view: ten triads (sets of three stanzas), each ending in the rhythmic refrain, “Desolation Row.” As recorded, the song is accompanied by acoustic guitars that begin quietly and become lashingly emphatic.

Modeling himself on his mentor, the working-class bard Woody Guthrie, Dylan has chronically concealed and denied his wide reading. “Desolation Row” uses Rimbaud’s hallucinatory surrealism to fuse T.S. Eliot’s “Waste Land” vision of Western civilization to the comic archetypal mythologies of James Joyce’s Ulysses. The Bible, Roman history, fairy tales, Shakespeare, and Hollywood movies fly by. Dylan’s muse here is, I believe, Billie Holiday: “As Lady and I look out tonight/ From Desolation Row.” He is listening to a record by Lady Day (as she was reverently called by jazz musicians) and has assumed her melancholy insight and personal trauma as his own.

Each triad of “Desolation Row” exposes the lies, limitations, cruelties, or collateral damage in different sectors of society: politics, law enforcement, and racial injustice; heterosexuality (set in a hostile gay bar); religion; science; psychiatry; the legitimate theater; corporate careerism; universities and English departments. Desolation Row is a state of mind, a self-positioning at the margins, where the artist identifies himself, like the Romantics, with the dispossessed, the outcasts and losers.

In the final triad, after a mournfully piercing harmonica solo, Dylan himself appears, addressing someone whom I suspect is his mother. She has probably sent him a chatty letter about his Zimmerman relatives, whose name he had long cast off. Dylan the artist, taking Lady Day as his foster mother, bids goodbye to his old identity and to books and letters and everything processed by social norms. He will seek truth, if it is ever to be had, in direct experience and spiritual intuition.

After many experiments and permutations, “The Art of Song Lyric” now has a dual trajectory. I begin with the Appalachian ballad tradition from its politicization during the violent unionization of Kentucky coal-miners in the 1930s through the protest-oriented folk movement shepherded by Pete Seeger to Bob Dylan’s controversial turn to the electric guitar, then a symbol of commercialized rock ‘n’ roll. Folk-rock, Dylan’s creation, lasts barely five years but produces innumerable lyrics of high poetic quality, from Donovan’s “Season of the Witch” to Crosby, Stills, and Nash’s dreamily jazz-inflected yet ominously apocalyptic “Wooden Ships” (co-written by Paul Kantner).

Next we follow the African-American tradition from its roots in West Africa to the emergence of the blues in the rural South. YouTube has become a tremendous resource for video clips of West African “speaking drums”, call-and-response group singing, and melismatic vocal technique (probably Islamic in origin) that survived in American blues. The powerful religious current in African-American culture surfaced in the Negro spirituals (a fusion of blues tonalities with Protestant hymn measure) that white audiences first heard from the Fisk Jubilee Singers on international tour after the Civil War.

The blues spread into jazz and torch singing and then Chicago electric blues, the crucible of rock ‘n’ roll. The British blues revival of the 1950s and ‘60s produced great bands like the Yardbirds, the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin. Simultaneously, African-American soul music merged gospel singing with secular, romantic themes and, in Marvin Gaye’s landmark What’s Going On, a topical social consciousness.

James Brown, “the godfather of soul,” shattered European song format by returning popular music to West African style, an endless stream of exclamatory riffs over heavy, “funky” bass and percussion that gave birth to disco. In the 1970s, lyrics lost importance in hedonistic, producer-driven disco; with a few exceptions, political content vanished. But the invisible mastermind d.j.’s of disco clubs took their dual turn-table technology to the streets and by the late 1970s had created rap (influenced by Jamaican “toasting”) in the Bronx. Elements of rap had long existed in African-American culture, where rhythmic speech as performance was already recorded in the 1920s and probably had antecedents in the recitations of African griots (tribal bards).

Rap spread globally in the late twentieth-century and, under the general rubric of hip-hop, now dominates music industry sales. It helped inspire the poetry slam movement, which began in Chicago in the mid-1980s and went national in the ‘90s. Rap as an incantatory, improvisational form descends from the “dozens” or “snaps,” a competitive African-American game of escalating put-downs, cheered on by the group. Its fast pace and bouncing internal rhymes have enormous propulsive vitality. As an artistic style, rap is energizing and confrontational rather than contemplative or self-analytic. The voice is so weaponized that admission of fears, doubts, or ambiguities can be difficult. Themes are sometimes scattershot or undeveloped. Nevertheless, rap’s extemporaneous channeling of colloquial speech is so robust and dynamic that it makes most contemporary American and British poetry seem stilted, stale, and cloistered.

To complete the spectrum in “The Art of Song Lyric,” I do a brief survey of the major genres of hymn, aria, lieder, cabaret, and musical theater. But my primary goal is to give historical shape and context to the enormous body of modern popular music that young people now hear in random digital isolation, without the framing commentary by DJs in the old era of radio airplay. High-level song production is becoming depersonalized, with beats invented by digital whiz kids being handed off for slapped-on lyrics—an assembly-line contrivance then dropped in the lap of a star vocalist. The integral artistic bonding of music and lyrics is weakening. There is one solution, perhaps the only one: immersion in the lost poetry of music.

Shares