A day later, Prince’s death remains just as difficult to figure out: For anyone who grew up with his songs and saw him as a source of vitality, lust, genius and hours of head-spinning music, his passing is just about irreconcilable. For a musician who was intensely private, he was also someone we thought we knew, and he seemed like he would keep touring and making music forever.

To try to make sense of a deeply complicated artist, Salon spoke to the critic Touré, who’s written widely on music and culture and is the author of “I Would Die 4 U: Why Prince Became an Icon.”

We spoke to Touré from New York; the interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

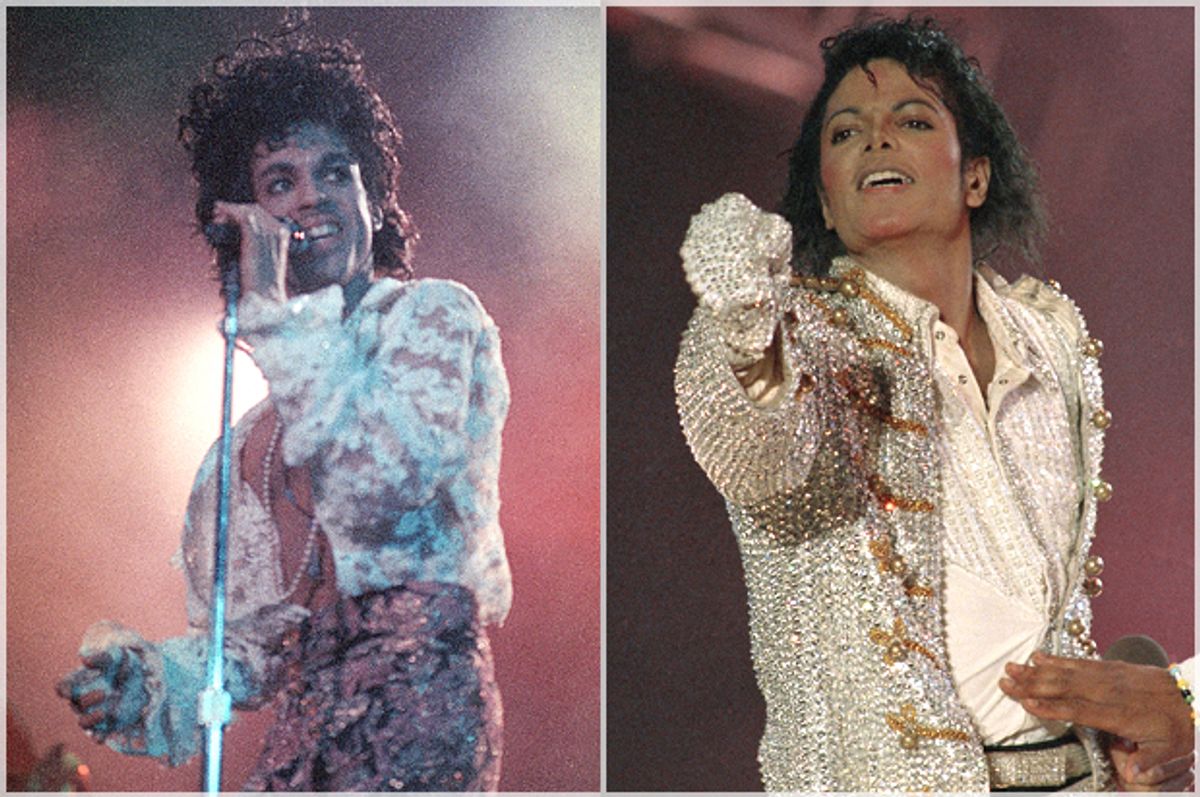

Prince and Michael Jackson had a rivalry that was very real, at least to Prince. Sometimes musicians’ fights are driven by the press, or made up to sell albums or newspapers. But Prince really meant it, didn’t he? It tapped into who he was and wanted to be.

It was a real rivalry. I know from people who were friends with Prince that he cared very deeply about the competition with Michael Jackson, the rivalry with Michael Jackson. You notice that “1999” and “Thriller” came out within a month of each other. And “1999” is Prince’s best-selling album to date – I think it sells two million copies before “Purple Rain” comes out. I think it’s the fifth best-selling album of that year. It’s a big success for him; he’s moving upward. He’s at least doubling the audience he’s had previously.

But Michael Jackson goes to the stratosphere and has the biggest album of the year and the biggest album of all time. And [Prince] is like, “I gotta get to that! I gotta be the biggest dog! I gotta get to that!”

So he’s spurred by Michael, and that led him to make some changes with “Purple Rain” that led that to being the album it is — widely accessible pop-rock instead of the edgy soul and funk he’d been doing earlier.

And at one point, Michael sent Prince a song called “I’m Bad,” with hopes that Prince would jump in it and they could collaborate on the song together. Prince was so offended at the notion of Michael Jackson doing a song called “I’m Bad” – in a world where Prince existed as an actually bad person – Prince re-recorded the song, and sent it back to Michael, like “Here’s how you should have done it.” It was kind of a superstar way of saying, “Fuck you.”

At what point in his life was it important for Prince to be the biggest? Sometimes when people become artists, they went to do great work, be the best – but being a superstar was clearly part of what he was aiming for.

I think it was his whole career, that he wanted to be the biggest. [Writer and tour manager] Alan Leeds told me that as a teenager, [Prince] was not working and planning on being a musician – he was working and planning on being a rock star. That’s what he wanted for himself.

He was escaping a very difficult home life. There was no nostalgia, nothing he wanted to go back to – he wanted to escape that world. The farther he got, the faster he ran and the faster he was able to run.

Prince was so lusty, and brought explicit sexuality into more-or-less mainstream music. He was also deeply religious. How did you see that contradiction working out?

I don’t see it as a contradiction, and I think he would argue that it’s not. In his music, he sees sex and sexuality as part of spirituality. God gave us these urges, so they can’t be unholy.

There are these great moments throughout the songs where you get the erotic and the divine being intertwined. This is historic and classic in black music – mixing these two. But Prince did it in a more propulsive way.

Think about a moment like in the song “Adore,” they’re making love, and angels are watching because their love-making is so serious and beautiful. They need each other. And this is like heaven not only affirming but wanting us to have this meaningful, passionate sex because that’s what good living is all about. So there’s not this barrier between Saturday night and Sunday morning: They were together in one cosmology.

He was sincere about his religion. How important, how active a part of his life was it? Reading the Bible, talking to friends about it…?

He grew up Seventh Day Adventist, and that was very much a part of his life. You can hear a lot of the messages from Seventh Day Adventism in his music.

When he was a little bit older, he had a three- or four-year argument with [bass player] Larry Graham over Jehovah’s Witnesses. Larry Graham quote-unquote won, and Prince said, “Okay I see it your way” and became a Witness. He took it very seriously. I have people who said he was going around Minneapolis, knocking on doors.

Prince was born in 1958, the Boomer heyday. But he really wasn’t a Boomer, entirely, you’ve said. In some ways he was a quintessential Gen X artist.

He was a Boomer, as far as when he was born, but he had this impact on Generation X because he’s sharing a lot of the experiences that they go through – a lot of the experiences that draw a generation together. Experiencing divorce, familial dislocation – that’s a huge experience for Generation X. We’d typically call them a “latchkey child” – but he was more an abandoned or homeless child. It was a dire situation even though he worked his way out of it.

That point can’t be underlined enough: As far as I understand, he was basically functionally homeless at about 12 or 13 years of age, and goes to live with somebody else who cared for him but also had four or five other children to take care of, and was in graduate school at the time. So who was really taking care of him? And really focused on him? I don’t know.

And he built himself from that into all this.

Shares