One of the most magical aspects of growing up is fantasizing about your future career. Will you be an astronaut? A surgeon who saves lives everyday before rushing home to a cocker spaniel? A stay at home mother devoted to her children? For me, it was a writer — always has been, probably always will be. As a kid I poured over books and magazines in the hope of absorbing the necessary skills to land such a cool career. There’s something fundamentally interesting about meeting influential people, and something incredibly powerful about being chosen as the person to tell their story.

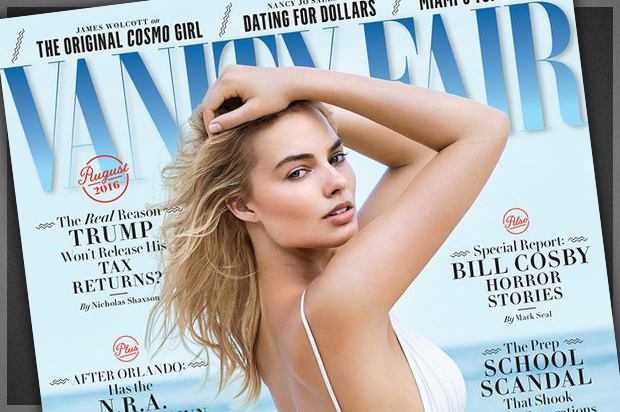

Margot Robbie wanted to be an actress. From a young age the native Australian felt inspired to perform, but thought the life of a movie star was exclusive to those from Hollywood. I learned this information about the actress from a recent profile in Vanity Fair, a magazine I’ve always aspired to write for. That’s what a profile ought to do — inform us on the subject and help readers gain perspective of the person as both an individual and creative professional. Like any good profile, the one in Vanity Fair, written by Rich Cohen, left me as a reader wanting more. Unfortunately, as a woman and a journalist, the piece was found lacking for a number of reasons.

“Welcome to the Summer of Margot Robbie,” boasts the glossy headline of the piece. Upon perusal of the lede, however, it’s clear we’re being introduced to a derivative cliché we’ve come to accept in celebrity profiles: the over-eager journalist gushing over the attractive young female star.

Profiles are tricky because of the false sense of intimacy required. Your subject is aware they’re expected to reveal a certain amount of details in order to make for a good story, while you as a journalist know it’s your responsibility to do your best to make the subject comfortable enough to speak freely. Often, interviews are held at a restaurant or hotel, intimate settings for any sort of interaction. But it’s not acceptable to write about what’s essentially a work meeting like it’s a date.

In the Vanity Fair profile, Cohen saturates the narrative with the tale of just how lucky America is to have Robbie grace us with her on-screen presence. To be certain, Robbie has made a name for herself for her roles not only in “The Wolf of Wall Street” but others such as “About Time” and future flicks that include “The Legend of Tarzan” and “Suicide Squad.” What’s remarkable about Cohen’s descriptions is how many demographics he’s able to insult in one fell swoop. Within the span of a few sentences, the profile insults America for having to outsource its movie stars from Australia, insults the country of Australia as if it’s sheer dumb luck Robbie’s star happened to land there before moving on to the big time, and most importantly insults — and condescends to — Robbie herself:

“She is 26 and beautiful, not in that otherworldly, catwalk way but in a minor knock-around key, a blue mood, a slow dance. She is blonde but dark at the roots. She is tall but only with the help of certain shoes. She can be sexy and composed even while naked but only in character.”

As if she’s another specimen there solely for his observation. This task was complicated for Cohen who explained Robbie “is too fresh to be pegged,” but goes on to compare and objectify her: she’s a blue mood sort of gal — whatever that means — and is tall when she wears shoes (as people, especially women in high heels are typically wont to be). She “wandered through the room like a second-semester freshmen.”

Cohen’s driveling description captures a somewhat common trope of romantic desire that causes a person to want to have their cake and eat it too: Robbie can’t be quite pegged due to her exquisiteness, so why not reduce her to her sexuality and saccharine terms few people would want but certainly understand?

Unfortunately, this is par for the course when it comes to celebrity profiles of women.

Singer Sky Ferreira recently made headlines following a LA Weekly profile that likened her to a “freshly licked lollipop.” The article, boldly entitled, “Sky Ferreira’s Sex Appeal Is What Pop Music Needs Right Now” fails Ferreira the same way Cohen fails Robbie, in that the journalist tasked with the story wrote his sexualized and romanticized fantasy of his subject, rather than adhering to the reporting and etiquette necessary to accurately tell the subject’s story. Robbie and Ferreira were failed when the journalists decided to take agency over stories that were not their own. Profiles are intended to let us know about the subjects, not impress us by how unremarkable a lunch time outfit was before descending into descriptions of sex scenes, or details about similarities to Madonna via “shared cup size and ability to cause a shitstorm.”

I’ve written profiles on attractive subjects before, and understand the allure of being so close to someone so attractive. It’s easy to get carried away and swept up in the charisma, but part of the responsibility of the assignment is to set aside whatever sort of crush may develop.

And yet profiles of women like Robbie and Ferreira are still shaping the way we read about women, and to an extent the way women are written about. A 2013 profile of Megan Fox in Esquire describes the actress as “a screen saver on a teenage boy’s laptop, a middle-aged lawyer’s shower fantasy, a sexual prop.” Readers were aghast at the irreverence for Fox printed in a respected publication. But the story ran and was met with widespread circulation and collective shrug of “well, she’s hot — what did she expect?”

It seems female celebrities are written about most fairly when interviewed by a female journalist. A recent example is Laura M. Holson’s Time’s piece on Cosmopolitan editor Joanna Coles, written with descriptive language and aplomb. Additionally, Miranda July’s profile on Rihanna eloquently captures the experience of mixed awe, admiration and respect felt when working with such a star without being creepy. I’m not sure whether it’s a facet of womanhood male writers actually cannot see or process, or such an ingrained behavior to sexualize women without a second though they’re subconsciously blinded to it, but it’s just so exhausted. Some celebrities cut out the middleman completely, and write for themselves as Emily Ratajkowski did in an essay about shaming girls for their sexuality in Lenny Letter.

Once this article runs, I’m certain I’ll catch heat on Twitter and other platforms for being something akin to “an angry, single woman,” and that’s perfectly okay. Yes, I’m angry that talented women are treated so poorly in what’s supposed to be professional settings, but my anger is not misplaced, let alone singular in this regard. Our culture has come to accept the tendency to encourage women’s creative and professional ambitions, only to celebrate them in terms of whatever degree of sexuality they bring to the table. We should all expect so much more.