This article originally appeared on Narratively.

“Hey Penny, is Carrie awake?” I ducked through the screen door, letting it bang shut behind me. The sun had barely crested the Seattle skyline and I was already at my best friends’ house. Her mom, Joy, grabbed a bowl from the cabinets and a box of cereal and set it on the kitchen table. “I’ll go check,” she said. I pulled up a stool and sat down, pouring out the sugary cereal and adding the milk that Penny, Carrie’s other mom, fetched from the fridge.

“Hey Penny, is Carrie awake?” I ducked through the screen door, letting it bang shut behind me. The sun had barely crested the Seattle skyline and I was already at my best friends’ house. Her mom, Joy, grabbed a bowl from the cabinets and a box of cereal and set it on the kitchen table. “I’ll go check,” she said. I pulled up a stool and sat down, pouring out the sugary cereal and adding the milk that Penny, Carrie’s other mom, fetched from the fridge.

More from Narratively: “Babies for sale: The secret adoptions that haunt one Georgia town”

It was the summer before my mother left my dad. My twelve-year-old self lived in books and fantasy worlds of unicorns and dragons, rather than the real world of dark bruises and a shattered living room lamp, swept up and never discussed. Unlikely friends, proximity brought Carrie and I together more than anything else. We were the only two girls our age in the neighborhood.

More from Narratively: “When you die, I’ll be there to take your stuff”

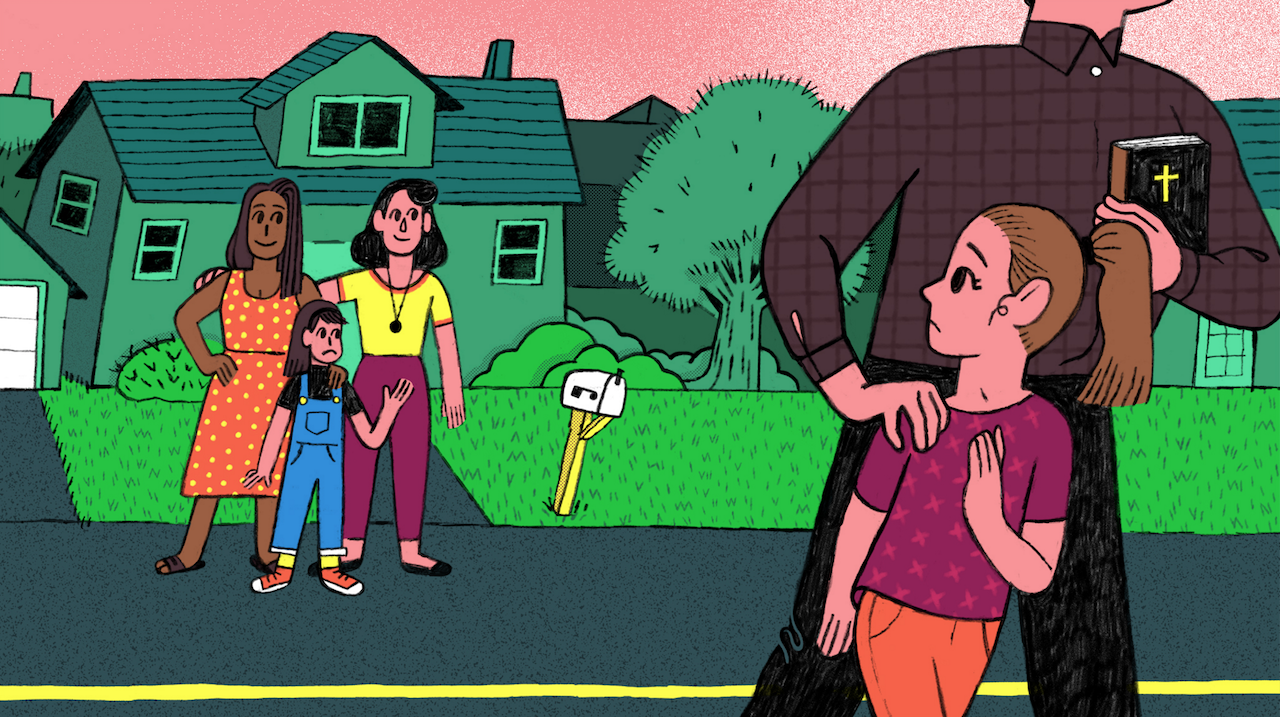

My strictly religious family attended church every Sunday morning, worship services on Sunday night and Wednesday night youth group. I’m not sure if Carrie had ever been to church. Her two mothers, Penny and Joy, lived around the block from my parents’ brick Edwardian house in a small two-story bungalow that they were constantly improving. They played the Indigo Girls on their stereo, danced around their kitchen and talked about summer solstice as casually as my mother discussed the church bake sale.

More from Narratively: “My baby was stillborn. But I refuse to hide him from the world”

I only went back to my house to sleep, escaping out the back door every morning before my dad could catch me. If I slept through my alarm and he hadn’t left yet to meet a client I’d have to stand barefoot in the kitchen and recite my assigned Bible verses for the week, or share with him the prayer requests he required me to write on 3×5 index cards. My mom taught kindergarten, and had the summers off, but while physically present, she wasn’t really there. She moved in a daze through my father’s shouted words and hid for hours in the bathroom, planning the escape she’d execute later that fall.

Every morning I’d show up on Carrie’s doorstep and her mothers took me in. They never asked why I was there and never told me to go home. They acted like it was perfectly natural to have a second daughter.

At the top of a hill that overlooked Seattle, Carrie and I roamed in and out of back alleys, eating fruit that had fallen from neighbors’ trees. Ripe juice dripped down our arms, staining our cutoffs red. We rode our bikes in circles through the crushed glass and burnt stubs of fireworks left at the elementary school’s concrete yard after the Fourth of July. And at nights, when the air hung hot and humid, we’d play truth or dare. We prank-called the boys at school who’d made us cross our legs in class. We egged the neighbor’s house after she yelled at us for eating plums from her trees.

“Truth,” I picked, tossing the well-read issue of Sassy on her bed. After I’d ripped the inseam of my brand new, eighty-dollar Guess jeans trying to scale the fence around the local cemetery I’d been going for the truth option more.

“Have you ever kissed a boy?” Carrie asked. We collapsed into giggles, tanned legs wound together and thighs touching, and later lied to her mothers about the hot pink nail polish we’d spilled on her comforter.

Our games veered back and forth between the children we’d been and the women we’d become.

Too many things were changing all around me. Earlier that year, I’d read the headline “War” on a newspaper and it wasn’t in a history class. Signed out of all sex education classes by my religious parents, I had no idea what was going on with my body. When short, curly hairs started appearing between my thighs I cut them off with craft scissors, stuffing them into the bathroom wastebasket. And I sensed changes coming in my family, the way you can sense a summer rainstorm hanging in the clouds just before it lets loose.

“We’re going swimming at Greenlake, why don’t you run home and grab your suit?” Penny tossed out the suggestion, and I’d duck through the back alley and run home to tell my mom I probably wouldn’t be back for dinner. Trips to the lake, meals out at local restaurants or crowding around their kitchen table for pizza; I took for granted that I was included. With the myopic focus of youth I never wondered why they’d opened their home to me so thoroughly.

That winter, my mom finally left. A ’90s latch-key kid, I was the first one home every day. The day she moved out, I opened the back door and walked into a bare kitchen. There were no chairs in the breakfast nook, or around the dining room table. I wandered through the house, past empty closets and vanity drawers that now held only the crumbs of blue eyeshadow and pencil shavings. She’d left no note, no explanation and given him no warning. It wasn’t until my twenties that I assembled all the cracked and jumbled pieces of my parents’ marriage into the shape of a missing living room lamp.

Once she’d left, my Dad noticed how much time I’d been spending at Carrie’s house. “Hate the sin, love the sinners!” he’d remind me at the nightly dinners we ate around the dining room table. I now had a bedtime, and he’d sit cross-legged on the floor by my futon and read passages from the Bible. I’d stare out the open window, up at the stars, while he read, “If a man lies with a male as with a woman, both of them have committed an abomination.” Then he’d quiz me.

“Dena, pay attention.” He’d snap his fingers under my nose. “Do you understand? Penny and Joy are going to hell, but you can save them. You have to tell them about the Good News.”

I’d sigh, roll on my side and present him with my back. Any rebellion, no matter how small, had to be carefully chosen. The boundary between the territory of what I could get away with and a slap across the face constantly shifted. “Yes, Dad.”

My parents’ divorce dragged on, and the house went up on the market. It was winter and, trapped inside, Carrie and I switched to listening to Madonna’s “Immaculate Collection” and practicing our dance moves. We decided to stage a show for her moms in their living room, setting up chairs and bed sheets that hung from the ceiling. Wearing blazers borrowed from their closet and black bras stuffed with tissue, we went all out to re-create her “Express Yourself” video.

I don’t know why my Dad showed up that night to sit, awkwardly perched on the edge of a folding chair, and watch our performance. I remember his stilted clapping and forced smile, the way he grabbed me by the arm and dragged me out of there. And suddenly I was busy watching my younger brother and sister, preparing meals for the family, and doing laundry, without any time for childish things like playing dress-up. Early that spring we moved across the water to Bellevue, leaving behind their bad influence. Even though I begged and pleaded, somehow there was never time to go back and visit the old neighborhood. The divorce went through and my Mom moved to Bellevue, too. I didn’t understand the how and why of her leaving until I was older. For years we had a difficult relationship, until I gained the maturity and experience to understand my parents’ marriage.

The last time I was home was for my mother’s funeral, in February of 2009. Afterwards, drained and exhausted, I begged my now ex-husband to drive with me to my old house. I gave him directions, the route burned into my memory even after fifteen years. Up the hill, past the graveyard where I’d torn my jeans. Around the corner, past the elementary school where they’d rebuilt the playground, tearing down the old wooden structures and replacing them with bright, colored plastic.

The trees had grown to shadow and shade the entrance to my old house, hiding it from the street. We parked, and my ex stayed in the car while I walked around the block and stood on a sidewalk littered with evergreen needles. When I rang the doorbell, no one answered. There were no names on the mailbox, and no way of telling if they still lived there.

They chose to love me even though they knew that I was being taught to hate them. They listened to my father’s lectures about Jesus with a patience borne — I can see now, out of a desire to continue being a refuge for a lost and scared little girl.

For one glorious summer they gave me the gift of freedom, a home and a safe place to hide.

When I finally responded to my husband’s persistent honking and turned away from their front door, words and memories jumbled inside me, clogging my throat. But as I opened the passenger door and climbed inside, I looked back at the house that had sheltered me and whispered, “Tell them I said ‘thank you.’”