One of the most important but also briefly lived chapters in rock history was glam, the primarily British movement that produced David Bowie, Roxy Music, T. Rex and the New York Dolls. After a few years of visual dullness and denim in rock culture, glam (often called “glitter” in the UK) channeled glamour, theatricality, style, and sexual ambiguity.

For all of its visual extravagance, much of the music itself was straightforward — pumped-up blues songs played by musicians in wigs and fancy shoes.

A new book, “Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and Its Legacy, from the Seventies to the Twenty-First Century,” chronicles the movement and argues that its influence is deeper than ever.

Author Simon Reynolds is a veteran British rock critic, now living in Los Angeles, who is also the author of “Rip It Up and Start Again: Post-Punk 1978-1984” and “Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past.”

Salon spoke to Reynolds from Los Angeles, a few hours he left for his British book tour. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Let’s start with the roots of glam rock. The standard take on glam said it was about sex and gender, with the musicians coming up with various ways to re-imagine them. This is the idea that Dick Hebdige floated in “Subculture.” You’ve argued that it’s really about artifice and a self-conscious kind of persona and theatricality. Is that what you see holding together all these different acts?

Well, I think it’s a mix of all of them and they’re all linked in a way. You know, like androgyny and sexual fluidity relate to dandyism and men taking an excessive interest in their appearance, but androgyny and gender bending relate to camp which relates to theatricality. It’s all this sort of mixture. All these things lead to another, and then decadence is another concept, you know.

How does decadence fit in?

You know, one of the things is the idea unmanliness, of men failing to do their duty, having a stiff upper lip, and sort of be basically military or patrician. Decadents are often aristocrats who didn’t do their ancestral duty of going out to defend the empire.

Glam kind of drew inspiration from these somewhat garbled ideas of what decadent Berlin was like. Bowie wrote a song inspired by the bright young things of 1920s, the dandies of 1920s [London]. Oscar Wilde is an influence. You know, I think that they’re all sort of jumbled together.

What were the musical precursors, then?

The Rolling Stones were as important as Lou Reed was during that period. The Rolling Stones sort of actually anticipated a lot of these things. They were wearing makeup, they were camping it up on stage — I feel like Bowie had this rivalry with the Stones. He wanted to do something more shocking than Mick Jagger, and so some of the things of glam, you already see glimpses of them in the mid-to-late '60s. I mean, that’s when androgyny becomes a thing; men with two inches of hair longer than normal was considered like ragingly effeminate.

Bowie kind of upped the ante on that; the next step of being shocking is taking on ideas from the gay underground.

I wanted to talk specifically about Bowie because he’s a figure who runs through most of the book and also because he’s such an enormous artist. Since his death people are assessing Bowie’s complicated place in everything. I wonder how central he seems to you and to the glam movement, and also the degree to which he was a follower and to what extent he was a leader.

I think it’s bit of both. He’s a central thing because he did — he was more active. He did more moves, more changes, more stuff, really. He put Lou Reed back on, in the direction to his only real hit, I think, “Walk on the Wild Side.” He tried to make Iggy Pop a star. He gave Mott the Hoople their biggest hit ["All the Young Dudes"] and sort of changed their direction a lot.

What surprised me is he sort of went from seeming like a loser, he seemed like a one-hit wonder. And then all of a sudden, almost in a matter of months, he’s not only the person everyone’s talking about but he’s like the person who has the Midas touch, and his heroes have become his proteges and he’s mentoring them and producing them.

He seemed like the man who’s at the center of it all. So he did become a dominant figure, but I think he’s sort of astute at picking up what others are doing and so you know, Marc Bolan was doing a lot of this first. They had sort of a friendly rivalry. They were friends who nonetheless had this urge to be bigger than each other and be more famous first. He was inspired by what Bolan did. When Bolan was putting glitter on his face, Bowie was still a bit of a kind of hippie and making progressive-rock kind of sounds, acid-rock kind of sounds; much of “The Man Who Sold the World” is still late sixties in vibe.

And then he sees Bolan’s success and that shows him a way to leap forward. And also, I wanted to give a bit of credit to Alice Cooper as having made a lot of these moves before, slightly before Bowie: the theatricality, the spectacle, the sort of weird mixture of rock and musical theatre. Alice Cooper was a huge fan of musicals and Broadway and Hollywood, and Alice Cooper also was, you know, wearing a dress in the sexy way that Bowie was. There’s nothing really sexy about Alice Cooper, but in a more grotesque or alarming sort of way, but yeah, he was wearing a dress before Bowie was, I think.

You know, it’s interesting, a lot of the bands we’re talking about here, T. Rex among them, didn’t really do that well in the States compared to the UK. So I wonder generally how big the disparity was. And why do you think glam rock landed so differently in each country?

Yeah, that was something. It was quite marked. I mean glam was huge in Britain and T. Rex had, I don’t know, five or six number one hit singles, and I believe a dozen top ten hits in quite a short burst of time. And Slade had six number ones. All those bands-- Bowie, The Sweet -- they all were huge.

In the States, you mean or…?

In the UK. In America, The Sweet had some big hits. Bowie became a very talked about figure in America and covered heavily in magazines like Creem and he is an international sensation. But his record sales, for a long while, were very modest compared to -- you know, I looked very carefully at the album charts, and the stuff that was selling from Britain in America at that time was Humble Pie, Elton John, Jethro Tull. The solo careers of The Beatles were huge things in America at the time, and glam -- UK glam -- Alice Cooper did well, but UK artists are really not performing on Billboard and really not doing that well on radio.

There are three exceptions, I think. New York is obviously a glam center because of the New York Dolls and the whole Warhol scene. It’s an inspiration to be like Bowie, but it’s also one of the most welcoming cities, and then LA is obsessed with glam and there’s this really vibrant, somewhat decadent and debauched glitter scenes based around The English Disco. And, you know, visiting British bands are treated like gods. Silverhead are like: A band that didn’t even make it in Britain become a mascot of the groupies in LA. Cleveland had a very progressive radio station whose name I’m blanking on. They played all the stuff very early, like Bowie and even I think The Sensational Alex Harvey Band who were this great theatrical band in Britain that never quite became pop stars, but were like a really big live band and talked about a lot and celebrated by journalists. That was one of the only places in America that played records by The Sensational Alex Harvey Band.

WMMS is the name of the station?

Yeah, Cleveland has always had this very advanced, and slightly Anglophile orientation in its music scene which I think is why Cleveland had groups like Pere Ubu.

So, I think Detroit also was actually quite receptive to glam, because of The Stooges being there and Alice Cooper was based there for a year or two, I think.

Why do you think, though, there were only a few exceptions, while Britain was so much more enthusiastic?

It’s probably a bunch of cultural reasons. I think there’s generally in American rock culture, not as much interest in the visual side. I think there’s this feeling that show business is over there and rock has nothing to do with it, and generally speaking, American rock bands in that era did not go in much for theatrics and even when they did, like The Doors, it wasn’t theatrics with props or with stage drops or costumes.

But, you know, in Britain there were already bands like The Crazy World of Arthur Brown that was like, you know, the circus. There was fire. There was costumes. There was all kinds of stunts going on, and I think there is a British tradition of the musical where early rock ’n' roll in Britain a lot of it came through the music hall. Those were where bands played and they quickly sort of realized that having a gimmick, a visual gimmick or routines or something, went down really well.

So some of the first types for glam were happening the early sixties with people like Screaming Lord Sutch who had a whole -- He went around when Alice Cooper got big, saying "Alice Cooper ripped me off" because he would do things like get out of a coffin on stage and all this kind of horror movie stuff which he probably got from Screamin’ Jay Hawkins actually. But yeah, I think there’s more of a bent within British culture towards sort of music-hall, show biz blend with rock. I think it’s more of a British tradition to do with gender-bending as well.

Yeah! I was just about to bring that up.

Some of our most popular entertainment figures that you see on TV were female impersonators. Danny La Rue was huge. When I was growing up, one thing I noticed a lot was it doesn’t take a lot to make a British man put on women’s clothing as a laugh and also as a kink as well, as one of the British private kinks. You know Keith Moon was always putting on women’s clothing. There are all these amazing photos of him dressed up as a woman. I remember for charity people on local soccer teams would put on women’s clothing, go down the streets with a wheelbarrow to collect money. The pantomime game is always a man dressed as a woman. A bit of gender-bending and a bit of camp is nearer the mainstream of pop culture than it was in — well there’s “Some Like It Hot” in America. But I don’t think it’s quite — it’s more of an underground thing, isn’t it? Drag, I think.

Yeah, it’s more threatening and more off the mainstream than in your country —

You’re a much more seriously religious country, I think, than Britain.

Right. That’s for sure.

I think the glam things sort of take a while to come through in America, and I think glam’s real coming in America was hair metal.

It’s a lot of the ideas in the dandyism and a lot of the conceptually nasty ideas are gone, but the basic thing of men who look like women, wear loads of makeup, is coupled with a more sort of a heterosexual and sexist sort of attitude.

Definitely their image. All those groups — Motley Crue, early Guns n’ Roses — Axl Rose is covered in makeup. That’s where it comes through, I think. It was a time lag.

Yeah. Right. The most macho and masculine style of music suddenly picks up big hair and eyeliner.

It’s quite poppy as well; this rock that works as pop is what glam was, really. It was pure hooks and anthems, and great stompy beats, and hair metal is the same principles and that’s why it cleaned up on MTV, I think.

This was near the end of glam’s heyday, but: I’ve spent most of my life thinking that two of the greatest records ever are Roxy Music’s “Country Life” and “Siren,” which you deal with pretty briskly in your book. You seem to turn on Bryan Ferry and describe him as this sort of reactionary aristocrat. So I’m wondering how musically interesting you think that period of Roxy was and why you have so little love for the divine Mr. Ferry.

Well, I admire him as an artist, definitely. There seem to be two camps here between America and Britain. I notice American rock critics, like in the "Rolling Stone Guide to Rock" or Greil Marcus’s list of best albums of all time in the back of “Stranded,” “Siren” and “Country Life” are rated much more highly than the early records. Britain is the other way around because, for a lot of people, there was the shock impact: Right out of nowhere, seemingly, on “Top of the Pops” was “Virginia Plain,” and then the first couple albums, the first three albums, are really pretty weird and strange —

Those are certainly edgier.

To to me the weirdness of the first two albums especially, the fact that you can compare it to some of the stuff in groups like Can, to me that’s what’s really interesting, and the mish-mash of the weird proggy elements with this sort of post-modern pop art, classic songwriting -- the Noel Coward stuff that he was into, that’s what I find most compelling.

With those last few albums, they really try to clean their sounds up. I think the story is, as with a lot of bands, they end up in debt to the record company. So, their only chance of getting out of it is to break America, and so that’s what I feel that “Love is The Drug” is; a great song but I don’t find it as — it’s not experimental music in the way that — Like with [Brian] Eno I suppose. I wish Eno had stayed in the band, and they’d gone on to do three more albums like “For Your Pleasure.” which for me is like one of the greatest albums of all time. But, I actually like — I kind of like their second phase Roxy where they’re really going all out for pop and things like “Same Old Scene” and “Avalon.”

“Avalon” is a great record. In a way, I thought it was like Bryan Ferry saying like ‘Well I can do ambient music.

I think the thing is if you’re as left politically as I am, Bryan Ferry’s drift is disconcerting: That he sent his sons to Eton and they grew up to be rabid fox hunters. You know, he’s a very conservative figure now, Bryan Ferry, but he always, you know, he always had this obsession with aristocracy and interest in old money. You know, the line from one of his songs is something like “old money’s better than new,” and it’s sort of like he’s figuring out that world, you know. And eventually end up in it. He marries a very blueblood kind of woman and they put their children down for Eton as soon as they’re born. You know, the destination he ended up going in, I find sort of troubling. You know, it’s his life, he can do what he likes with his money.

You mentioned hair metal. But otherwise I’m wondering where you see the continued existence of this movement which we think of as being an early to middle seventies thing that was kind of over by the time the Pistols hit?

That’s what I found was interesting. In a way it has been seen by a lot of people as this sort of fly-by-night, couple-of-years thing. But actually its influence is legion if you look at most of the punks -- at least half of the punks, I think, everywhere in the US too, but particularly in Britain, are glam fans. Two key members of Siouxsie & the Banshees met at a Roxy Music concert, you know. Punk is glamour turned inside out. It’s ugliness and offensiveness, but it’s sort of very stylized. The punks got in trouble for wearing swastikas, but you know Johnny Thunders wore a swastika, one of The Sweets had a swastika, you know there was a lot of playing with these shocking images before. Then in the eighties you have The New Romantics and Culture Club and who else? Mostly every band is the children of Bowie and Roxy.

Right. Right.

And it sort of comes in waves. There’s a wave and it’s hair metal. In the '90s, it’s sort of an anti-glam era, I think, except you do have Marilyn Manson who is the Alice Cooper of the '90s. In Britain you have Suede, and it’s a sort of cross between The Smiths and Bowie. And then I think one of the reasons I wrote the book was the last decade or so, I felt like there were a lot of echoes of glam and the return of theatrics and spectacle. Lady Gaga is the obvious inheritor — wants to be the inheritor, certainly.

Ke$ha was actually very influenced by glam and she uses glitter in her imagery a lot, like on her face, in album artwork, and on stage.

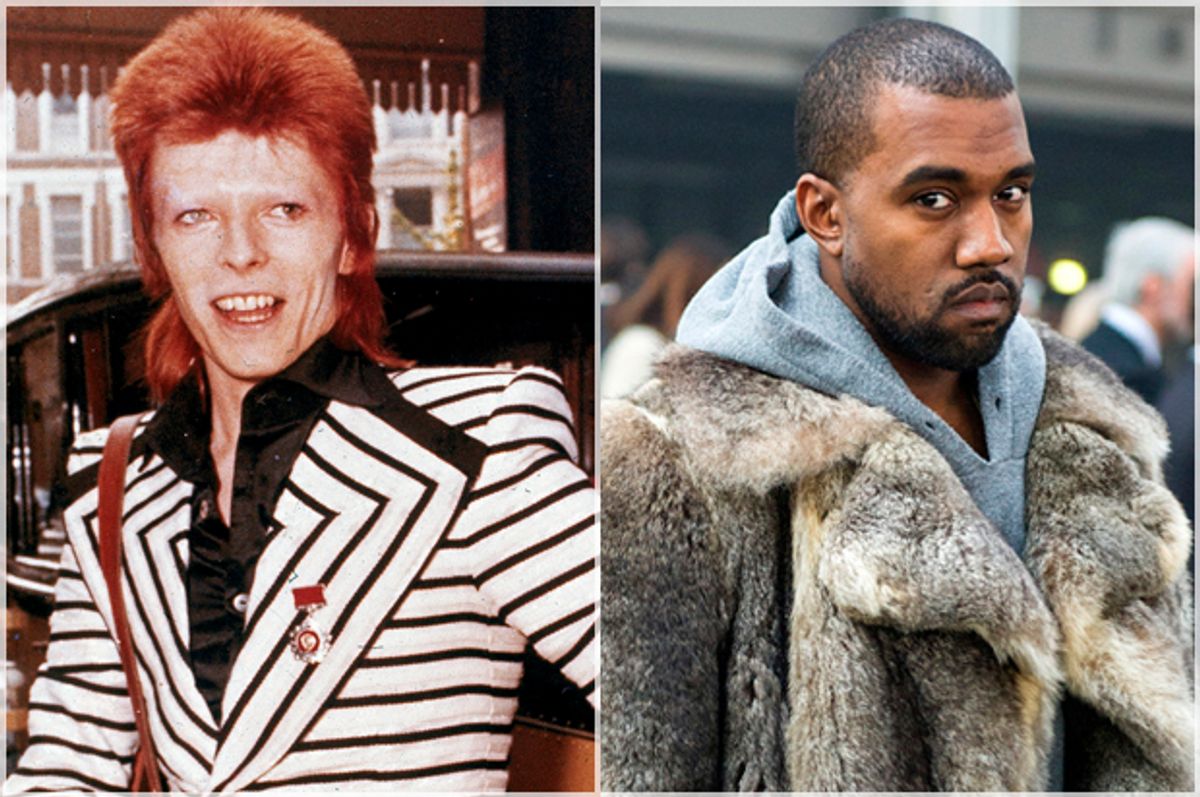

Also I felt one of the things that was defining of glam was this sort of writing songs about being famous or being a star. The way you see that a lot is in hip hop with people like Drake and Kanye West, well most of them really. It’s songs about fame and about decadence, about this dissolute life and how you’re quite unhappy. You have everything yet you’re quite unhappy. It’s hollow.

I would draw a straight line between “Fame” by Bowie and Gaga’s “The Fame Monster” album, and I think Kanye did this video this year called “Famous.” Fame is like his big subject.

I think that’s an odd reflexive, circular thing that’s going on, and that was a thing with glam. Bowie made it by writing about an imaginary rockstar with Ziggy Stardust. And, his biggest ever American hit was “Fame,” a song about paranoia, about the hollowness of fame, about power games amongst famous people, about — I think it’s about drugs. He thinks “what you need you have to borrow,” I think that’s a reference to propping up your ego with coke. I think that’s one of his greatest songs and I think it’s interesting that that was the one that made it to number one in America.

Shares