As a young professor in the 1970s, Henry Louis Gates Jr. would often take the train from New Haven to New York to meet with two elder statesmen, writer Albert Murray and painter Romare Bearden. Brought together by a love of the work of Ralph Ellison, Gates and what he calls “these two raconteurs” would take a long lunch full of stories, drop into Books & Company, and then retreat to Bearden’s apartment on Canal Street and talk endlessly, surrounded by art. Each encounter, Gates recalls now, was a “feast of a day.”

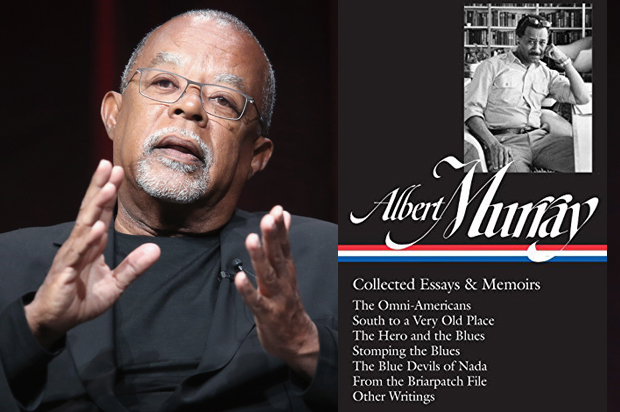

Now Gates, a Harvard professor and one of the preeminent scholars of black American culture, has paid tribute to Murray (who died at 97 in 2013) by editing “Collected Essays & Memoirs,” a new volume by the Library of America that drew a rave review in The New York Times. Murray was a critic of blues and jazz whose most famous book, “Stomping the Blues,” provided the intellectual underpinning of the revival of straight-ahead jazz in the 1980s and the high-culture adoption of the music form through programs like Jazz at Lincoln Center.

But Murray wrote more broadly on black and white culture, the links between them and America itself. “This is Albert Murray’s century,” Gates wrote in a New Yorker profile in the waning years of the 20th, “we just live in it.”

Murray wrote over decades; there were a lot of books and essays and so on. But there seems to have been one governing idea to a lot of his thinking, about race in America and the relationship of black people and white people. How would you describe it?

You’re absolutely right. He wasn’t a theorist of race in a universal sense but an Americanist. And he was an early proponent of the idea that race was a social construction. That was important. Now we take it for granted. But we have to remember that he was articulating this at the height of black power, an essentialist biological category. And in the black arts movement — which was the aesthetic wing of black power — the cultural was racialized; it was essentialized.

Murray said, This is rubbish — a) That’s the first thing. And then b) he said there is no such thing as white America and black America. This is long before Barack Obama and the Democratic National Committee. He said that black Americans and white Americans, Jewish Americans and Christian Americans mutually complemented each other. That their identities are forged in relation to each other. That there is no American culture without black culture. That there is no white American culture without black culture. And equally boldly, there is no black American culture without white culture.

He wouldn’t have known this, but I found an essay Carl Jung wrote, after his first trip to the United States. And he said, the biggest surprised to him about the United States was how black the white Americans are. He said, The Negro’s in your house; she’s in your life. He’s in your head!

What year did he write that?

I think it was in 1929; it was in the ’20s. It said that these white Americans were a different kind of white person — because of their interactions with black people. It was in their language, their demeanor, in the way they walked, the way they talked, in the way they hated. We could take that for granted today.

But Al Murray stood up to the black-culture essentialist nationalists and said, No! Culture is not biological. Race is socially constructed. And most boldly black people and white people mutually constitute each other into a new mix called American. And he did it powerfully!

I remember I read his book “The Omni-Americans” my sophomore year at Yale; I have a new edition by my bed. I’m reading it now, and I’m cracking up. Much of my political incorrectness and contrariness — talking about things like the African role in the slave trade or the fact that there were some black Americans who happily owned slaves for profit and were just as avaricious as any white person, that suffering is not inherently ennobling. . . . These are ideas that came to me from a number of sources, but one of them was the Murray-Ellison axis.

I wanted to ask you that. He was a friend of Ellison’s going way back, as well as a harsh critic of the other two major black writers of that period, Richard Wright and James Baldwin. So Murray wasn’t just a champion of things he loved but could call out very harshly things he thought were bogus.

It’s what he called the “social science-fiction monster.” I love that phrase. If you read the sociology of that period, of the ’40s and ’50s and ’60s — and a lot of black political discourse at that time — you’d think that all black people talk about at that time was white people and anti-black racism. While if you went into any black home or barbershop or beauty parlor — unless there’s a racial incident, unless Ferguson is on TV or Freddie Gray or some outrage — black people never talk about race.

What they talk about: What are the great themes of all art? Love and death. They’re what all people talk about, one way or the other, all the time. Or talking trash about sports or talking about world events. But it’s not all woe is me, up from slavery. . . . That’s a bunch of rubbish.

People are making culture, making art, with their lips, with their words — and being witty and signifying and riffing and laughing and being ironic about the world. It’s about transcendence. The most fundamental value of black aesthetics is transcendence, and that’s at the heart of the blues, as both Ellison and Murray wrote.

It’s not to wallow in angst or suffering because your baby left you or because you’re gonna die, because your baby left you or whatever. It’s to name it, so you can transcend it. And that is a cardinal value of black culture.

So ironically, Murray and Ellison and Bearden were the ultimate black-cultural nationalists. But they reached their position by debunking vulgar nationalism, people who would racialize culture. People who would have said, “You have to be black to teach black studies or to understand black history.”

That’s not true! You just have to sensitive and motivated. If someone said I could not teach Shakespeare because I am not primarily of Anglo-Saxon descent or Saul Bellow because I am not Jewish American, we’d say they were racist. But black people then and sometimes now make that bogus claim. And we in the black intellectual community need to stand up and said, “This is rubbish!”

It’s as silly as people saying if you’re black, you can’t be racist. I have no idea where this stupid idea comes from. But it’s one of the dumbest ideas I’ve ever heard. If you’re talking about “crackers” and “trailer trash,” that’s racist! If you say, “All white people are this or that,” that’s racist! It has nothing to do with the fact that we were subjugated in slavery to make America rich and prosperous in the 18th and 19th century. Racism is racism, man!

So Ellison and Murray went against the grain of the black arts movement. Ellison somewhere was called an Uncle Tom. And he cried. This was someone who devoted his life to celebrating the beauty and power of black culture, and writing what is arguably the finest novel — until Toni Morrison — ever written by an African American. To be called out as Uncle Tom by people too blinded politically to understand the subtlety of the the Murray-Ellison analysis. They were the same, two sides of the same coin.

But now they’ve been recuperated and now we know they’re visionaries. Of course, Murray wrote much more than Ellison. Ellison was paralyzed by that inability to write that second novel.

It’s tough when you write a first book like “The Invisible Man.”

Right, he wrote dazzling essays; they’re some of the great prose of the 20th century. But Al didn’t have that burden. He just kept writing. And Al was loquacious anyway!

Al had a real body of thought, as you can see in the first Library of America [volume]. The way he identifies the blues as the basis for the whole [black] aesthetic idea.

Yeah, I wanted to talk about the blues and how he changed the way we thought about it. Murray had a great line he gave in an interview. He was talking about black people and said something like “Europeans came up with psychoanalysis. We invented the blues. You invent what you need.”

It is like psychoanalysis, a way of confronting dire tragedy. But not to wallow in it but to transcend it. And about psychoanalysis, I’ll say this: It’s a beautiful [line], but black people also need psychoanalysis.

Fair enough! And white people also need the blues! A nice thing about the Murray-Ellison vision: We don’t need to take sides entirely on which of these things matter.

And part of what I think Murray argues in “Stomping the Blues” is that the blues come out of pain, of course, but there’s a lot of joy in there, too.

Right, he didn’t want African Americans and African-American culture to be the object of pathos, of pity. Our ancestors had faced enormous adversity, but they’d met that adversity by enduring. We had created a culture that deserved a seat at the table of world culture.

That’s an important claim, man! It was no accident that Murray was on the board that founded Jazz at Lincoln Center. Full disclosure, I’m on that board of directors. What’s classical American music? It’s jazz. What’s classical American culture? It’s sacred music, the spirituals. And we had to fight for the legitimacy for African-American culture even to be taken seriously.

I’m editing this Norton annotated anthology of African-American folklore with the great folklorist Maria Tatar, my colleague at Harvard. And I’m writing this essay — I’ve learned so much — about all these people who just trashed anything black, black folklore, black music: “It’s primitive, should it be collected? Is it a remnant of slavery?”

That’s why Murray is so important. He’s taking [that] on. What bothered him about the Moynihan report is that it reduces the complexity of the black experience to a pathology! That it was a reaction rather than an action. African-Americans were not sitting around saying, “Let’s see what some racist will do so I can react to it.” People were proactive. They fell in love. They saw beauty and named it. Sympathy, empathy — they felt it.

That’s what black culture’s about. And that’s the significance of Albert Murray. He said, We cannot allow ourselves to be confined by these categories invented by social scientists, who see all of black culture as a reaction to adversity. The irony for us is that that [bad] argument was very useful in the arguments for Brown v. Board [of Education].

They had to embrace the pathology argument to show that separate but equal is bad. So many good-hearted people who knew better said, “Separate but equal is bad, you need to abolish it.” But it was a deal with the devil. Black people had established all kinds of institutions that were as good as all-white institutions. But they had to argue otherwise, for the sake of a larger principle.

I wonder, with all this context, what Murray would make of the Black Lives Matter movement?

Murray, by definition, was skeptical of political movements. I think he would say, “Where is your text?” That’s what he would say.

I took a class at Yale once, “Revolutions and Revolutionary Thought.” Every great revolution has had a revolutionary text — even if the revolutionaries only read the introduction. The Bolsheviks had “Das Kapital.” Well, I doubt if many of them read much of “Das Kapital.”

“What is the text of this, brothers? Is it primarily reactive to police violence? Will it create a new civil rights movement?” He’d say, “Show me the goods.” I think he’d admire the energy, would admire their effectiveness at countering racist incidents when they pop up. But he’d ask, “How are you going to have legs? Show me your critique!” I haven’t seen that yet. Though [Georgetown University scholar] Michael Dyson on Sunday mentioned that there was a document I hadn’t seen yet.

You see, any political movement today has to explain how we can have the best of times and the worst of times in the history of black America. We have the biggest black middle class in history, but we have 38 percent of black children living at or near the poverty line. And we had 38 percent in the years after [Martin Luther] King died. How in the world did that happen?