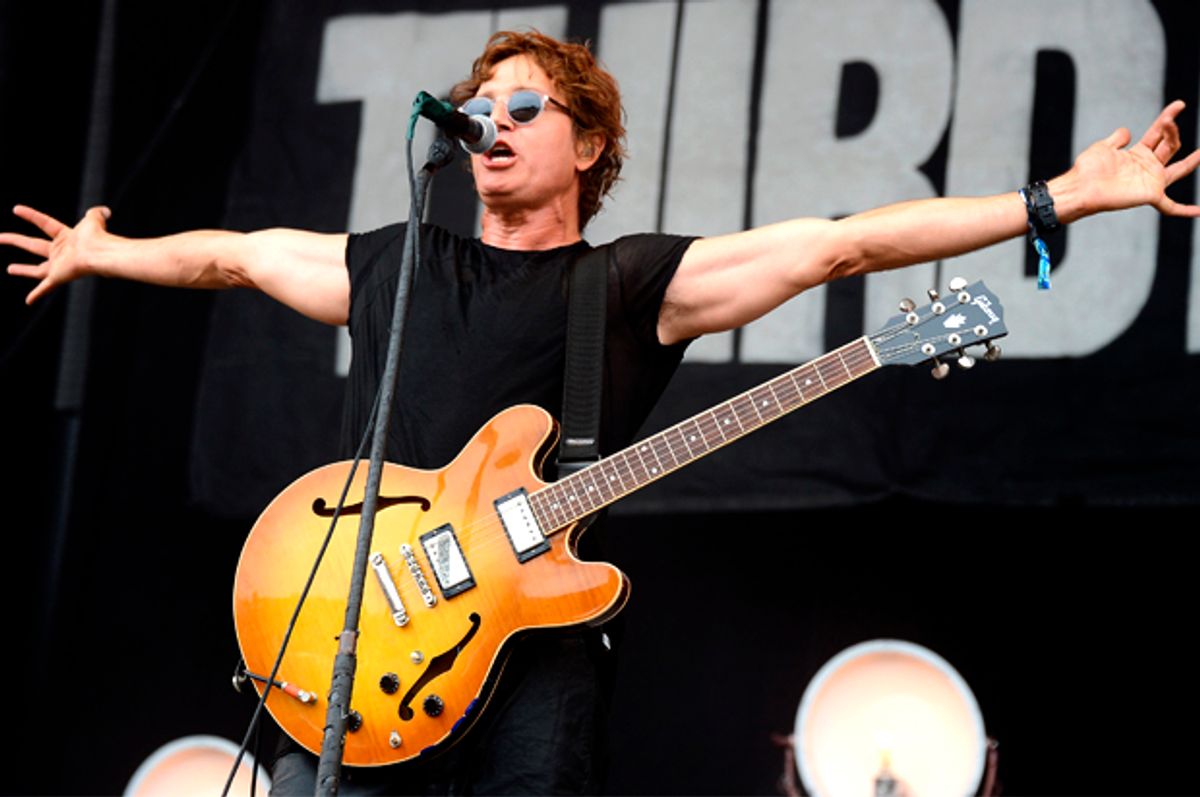

To some, Third Eye Blind is just another '90s nostalgia act, an "Alternative Nation" relic. However, very quietly (and perhaps to the surprise of many) the rock band has remained a popular touring and recording entity. More impressive, Third Eye Blind's fanbase has grown and expanded to include not just original supporters — say, those who discovered them circa 1997's "Semi-Charmed Life" — but also plenty of people who've found the group over the years.

This career endurance is partly due to smart touring: Third Eye Blind has done the college circuit and, in 2015, co-headlined a summer trek with fellow songwriting-geared group Dashboard Confessional. The group also has some vocal supporters from younger bands — including All Time Low, Sleeping With Sirens and Panic! at the Disco — who've kept 3EB relevant and in the public eye.

And, of course, it also helps that the band continues to release new music. The band's recent "We Are Drugs" EP is pleasingly diverse — from the crunchy, guitar-heavy power-pop of "Company Of Strangers" and the slinky electropop of "Isn't It Pretty" to the modern-sounding pop-rock earworm "Don't Give In" and "Weightless," itself a diverse song stitching together roaring guitars and more tranquil, meditative moments. "We Are Drugs" even has a song, "Cop vs. Phone Girl," addressing the widely shared 2015 video of a Spring Valley High School school resource officer assaulting a teenage girl.

Salon recently caught up with frontman Stephan Jenkins to chat all things 3EB. Besides a round of end-of-year touring, Jenkins says the band has April 2017 plans to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of its self-titled debut. Additionally, he discussed why he felt compelled to write "Cop vs. Phone Girl," his growth as a songwriter, and why Flume and Tove Lo's pop hit "Say It" is so "progressive."

Your new EP was recorded very fast. Why was this working process the way to go this time?

I think for a couple reasons. One, trust in self. I have come to trust myself more, and it's not because of any real growth in character or anything like that. It's because the trust that the audience has shown me has worn off [on me]. It's affected me. It's made me more confident. That's really the answer.

What I do a lot of times is, I will sit on a song for a really long period of time, because its not doing everything I want it to do. Or I'll second-guess and doubt myself, for whatever reason. And then I'll come back to it, like, a year later, and go, "Oh, what's that? I like that." So it's really just getting into that place of not judging yourself and not engaging in self-hate. All those usual things that artists tend to do.

I understand that from a writing standpoint. You write something and you're like, "This is terrible. I don't want to read this again."

Yeah, you know exactly what I mean. It's all the same stuff — like, writers just do it. We all do it. It's just being like, "You know what, it's fine. It is what it is."

"Don't Give In," the song on our new record — there's so much lyrical ambiguity on that track, where I don't have everything pinned down in the way that I do on a song like "Cop vs. Phone Girl." On "Cop vs. Phone Girl," I know that every word there is right to my standard. And "Don't Give In," I look at it and go, "It's not on the same level, but it is evoking a feeling that is working for me." [In "Don't Give In"], when I say "It doesn't work for you," I don't know what the antecedent is to "it." Before, I would just sit there and suffer over that endlessly, instead of being like, "I don't need to know. I need to know if it's evoking the feeling that I want to evoke when I sing it." And that's kind of a big step for me.

How difficult was that then, once you realized that was happening? How difficult was it for you to let it go?

Easy once it happened. Once it got going, it was like, "That's fine. You don't need it." [Laughs.] Also, I want to increase the tempo of making music, and put it out more often. So that's what we did. I'm working on sitting down and writing more songs. We're going to have another [release out] in April. It's going to be the 20th anniversary of our first record [1997's "Third Eye Blind"]. And there's several B-sides — well, they're songs that I wrote for the first record that we never recorded. I'm going to record those and put 'em on the record. So that's going to come out in April.

Next month I'm going to start songwriting sessions for an album that we want to put out next summer. And maybe that one will have five songs or seven songs. I don't know. I'm working more off happiness quotient now.

Which is nice because so many artists can't write unless they're miserable. They get writer's block when they have the happiness quotient.

To me, it's more like I look for inspiration. I can be inspired by a lot of different things, and when I'm in an inspired state, then I write.

Since you've had two decades to marinate on those B-sides, what was your take on them when you looked back in preparation for recording them now?

There's a song called "Tattoo of the Sun," and it's probably the first song I ever wrote as Third Eye Blind. It might be the first song I just completely wrote. It's still probably the most complete lyric that I've written, I think. [Laughs.] Yeah. That was just pent up for a long time: "I believe everything you say/'Cause you're not frightened the way I've been/So I follow you just in case you lose your way/So glad you let me stay around." That's exactly my insecurity in that time. I'm looking at this girl — the thing that's going to bring me some kind of wholeness which is never going to happen. [Laughs.]

Looking back 20 years, you get put right back into that place where you were. It's weird when that happens.

I was more evolved as a songwriter out of the gate than I thought. I feel good about 'em. I'm just really not good at judging or ranking my songs. I'm terrible at it.

Fair enough. You're close to them, and you don't have that perspective then.

Plus, it's just, I don't know. I don't watch myself on TV. I don't watch things that I do. I listen to my music a lot right up until I put it out, and then after that, I don't listen to it. I just move on. A lot of artists are that way. There's this thing with Fred Astaire, and he's dancing, and he sees a mirror and he shies away from it, moves away from it, because he doesn't want to be self-conscious.

I like that the new EP was so diverse. Each song has something a little bit different; it's versatile. It showed that there are so many directions you guys could go in the future.

I like that, too. Of course, you could not like it, and say it's a lack of cohesiveness. We were in the studio, and… God, we're such a good rock band. We just really are. There just aren't very many left. We don't have any sequencers, and we don't have any backing tracks. We've played for a long time together and developed that empathy as a band. You can hear that in a song like "Weightless," which is this exploration of a guitar rock band — tempo changes and signature changes. It's a band that's really in tune with each other.

And then a song like "Isn't It Pretty" — we were in the studio, and I told everybody, "I want everyone just to throw out whatever ideas you have, whatever your concepts are. You and your instrument. And let's just make up a song." And I had a bunch of lyrics in a notebook, and we started talking about beats and said, "Oh, I like this beat. This reminds me of urban smog before catalytic converters — like, '70s, '80s urban thing." That was the bassline. [Hums the bassline.] Had that almost like [an] Isley Brothers feel to it. Then that discussion prompted the guitar part, and then I started doing slam poetry on top of it.

That all just came in naturally with people not having any preconceived notions, and not saying, "Well, this won't be anything like 'Weightless.'" Or, "Do we have any definitions of what Third Eye Blind is?" The answer is, we don't. We don't have any; we don't need any. We just need to be open and musical in a room and shake that around. That was really fun. [Laughs.]

At the beginning of the interview, you mention the trust from your fans. One thing that's really impressed me about you and the band is how you've really managed to amass this multi-generational fanbase. I mean, I listened to you in high school, and that was the late '90s, but I know people who are 15 years younger than me who are massive fans of the band. I'm really impressed by that. Why do you think that is? How has the band evolved to be able to get this multi-generational fanbase?

I don't know. It's not a result of us trying to do that. It's a result of something that we were doing organically. I think that we are perpetually in a search to find meaning and connection in the context of the present tense. That brings people in perpetually. That's something that when, you know, when you turn about 15, you start to switch into that mode. Music becomes kind of an identity-generation device. It becomes a search mechanism and a clarifier for identity. And I don't mean it to be that; it's not my plan. It's just what we ended up doing.

I think there's a lot of seeking out your sense of self, and it's finding a way to live that has a real sense of aliveness while wrangling with things that are changing. That's very much what [the 2015 album] "Dopamine" was about. So much of "Dopamine" was about post-feminist politics. Like, the internal politics of post-feminism.

"We Are Drugs" is really kind of just about how surreal things are. [Laughs.] "Cop vs. Phone Girl," to me, it's all surrealism. It's a nightmare, actually.

I was going to ask about that song — obviously, I watched the video that inspired it, and it was horrifying. As a songwriter, what about it made you need to write about it?

Things can irk you, and they're non-hierarchical. You'll see somebody who's unarmed get shot, and you think it's appalling. And that's, you know, by any measure, of course, obviously worse than a girl being assaulted by an over-aggressive campus security officer. But that one, for no reason, stuck in my head. The narrative of it made some kind of dent in me. And that's how I write all my songs. They're all just based on something that makes some kind of dent, and that dent turns into some kind of lyric landscape. And then I make it fit into my life with music, I guess.

Usually those are about relationships and impact with friends, but sometimes something on the outside really makes an emotional dent. That was the case with "Cop vs. Phone Girl." Why? I think it's the surrealism of it. First of all, people expect somebody walking into a classroom with a gun in our society. Just that that's normal is so fucking insane to me. And then that person who is there to keep kids safe came in there clearly with the intent of teaching a lesson to [a student he perceives to be an] "uppity" girl.

That was just obvious to me. That, to me, is surreal; it's nightmarish. That the teacher stood by and let that happen — that the kids sat there, and they were stunned. But they expected it to happen. They got their phones out. They knew this was going to happen. This is part of their normal. Do you know when you lose your phone? You probably lost your phone this morning, right?

Yeah.

You lost your phone in the last 24 hours. You misplaced your phone for maybe eight seconds. Remember how you just freaked out?

Yeah.

The next thing you need to know is, "Where is my phone?" That child lost both of her parents, and she's in a foster home and she has a smartphone. You can imagine — if that's her connection to the world, you can imagine how important that phone is. That in this fucked-up institution that is a public school, if she turns that phone over, she very possibly wouldn't get it back. That would be catastrophic to her world. She can't give up the phone. She cannot give up that phone. She used it in class, she put it away, she sat there quietly, and the guy could not connect with her at all, because his — whatever, patriarchal sense of order could not accommodate that. His fragile sense of authority could not accommodate that. And I think that's perverse.

It is. It shows the empathy breakdown that has gone on in so many areas with society, it seems, especially this year.

Yeah. I was writing about it — it was an essay actually. I mean, I don't do it often enough, but sometimes I write pieces on politics for Time or Huffington Post. I kept meaning to write about it, but I kept putting it off. And then I looked at what I wrote, and it was notes. And I just started singing notes, and it just turned into a song. It's kind of how it came together.

It's funny, because the audience really loves it when we play it, but radio won't play it.

Really?

No, radio won't play it. And [W]BOS in Boston was kind of the bravest in this. They would brave the complaints that it got. But [radio] couldn't do it because they're all owned by big corporations. And those guys have to answer to big corporate sponsors.

Yeah, they do. And shareholders.

And shareholders. So they couldn't tolerate it.

You figure, in the '90s when you were starting out, how much music that was very protest-driven or spoke of important things, was on the radio. You'd learn about those things. People took a stance.

The only social consciousness song that I think is actually on the radio is Tove Lo ["Say It"]. And she sneaks it in. When she sings [sings] "When you say it like that, uh-uh-uh-uh," and then she says, "Let me fuck you right back, uh-uh-uh-uh," that's a social statement, I think. That's a progressive social statement. She's assuming a kind of sexuality that has been traditionally reserved for males and is seen as aggressive. She's presuming that sex is an activity she enjoys as well, which would make her [in the eyes of society] a slut, right?

She's not doing in a lascivious way. She's not doing it in a way that's, like, "I'm trying to tease." It's not like, "Give me some beads and I'll show you my tits" and responding to patriarchy. It has a post-feminist sense to it, in that it presumes its own sense of equality without seeking.

My definition of it is, is that it's a presumption of equality without taking males into the equation any more than males take women into the equation of their sense of equality. I've never once in my life thought that I needed to wrangle with or ponder whether I'm equal to a woman. Not ever. And you can just think . . . I mean, if you were in high school in the '90s, you can think of thousands of times you've done that. How deep that is in your psyche.

So when she says, [sings] "Let me fuck you right back, uh-uh-uh-uh," in a pop song, she's sneaking a — what's the word I'm looking for? -- a radical idea into people's consciousness, and I think it's interesting that she got away with it. There's nothing preachy about it. It presumes a state of being, and I think that's impressive.

Absolutely. That's exactly it.

Anyway. But we didn't get away with it. And I don't think I was being preachy either, I was saying the real account of what's going on. And then the release of the chorus is almost kind of an imagination of the world as it should be, you know?

People get uncomfortable when you actually spell things out — certain segments of people at least. I was going to ask how your campaign selling the "Raise Your Hand If You Believe in Science" T-shirts went after you guys launched it.

Oh, yeah. We gave a bunch of money to the Hillary [Clinton] campaign, and she said it in her speech.

Did she really? That's pretty cool.

I mean, I'm so utterly tripped out by this election. I just think that 40 percent of Americans are just terrible judges of character. That's my sense of it.

Besides the release of the new record, do you have anything else going on that you feel is important to mention?

I work with a group called the Jimmy Miller Foundation, and we take service members, Marines, with PTSD, surfing. Surfing is therapy in itself. We don't give therapy; we just give surfing. And after I did that, I saw the Republican say . . . the quote was something like, "Some people aren't strong like you and me, and they get PTSD." And it was another one of these moments that really struck me, because his ignorance and casual dismissal and his condescension, and in that the perpetuation that PTSD is a weakness, instead of where it's like . . . a wound to the midsection from shrapnel is something where you should get a medal for, a Purple Heart, right?

Right!

It's the only time in the whole thing that put vitriolic hate in my heart, because I know these people. I've seen a young woman, she's probably 25 years old, taking her surfing and her rash guard came up out there, and her back had burns all over it. She had a thousand-yard stare on her, that just meant she had seen things that she would never, ever be able to explain. I saw her paddle into a wave that that fucking coward would never paddle into, because it takes martial courage to get in to a wave. I saw her come back, and the look on her face where you could see she was, like, coming home. I know this, because I've actually spent time with these people who serve. They're nothing but strong. That's part of why I work with them, because it gets me in contact with strength.

That's what I'm thinking about. That's what I'm doing right now. And when I think of people who support the military like I do, when I think about people who would vote for this guy, it just — oh, it really burns me up. It's almost hard for me to talk about. I was having trouble saying that to you, it makes me so angry.

Shares