The week before the 2016 presidential election, Francis Wilkinson wrote a piece for Bloomberg View headlined “The Moral Foundations of Trumpism.” The title was intentionally jarring. The moral foundations of a movement led by an accused sexual predator who has nourished and fed on racism, a proto-fascist, pathological liar, bullshitter and gaslighter? Or, as Wilkinson put it, a movement of “good, decent people supporting a moral delinquent who subverts many of their most basic values.” Believe it or not, that’s exactly where the idea of “Moral Foundations Theory,” or MFT, leads us.

MFT is a social psychology theory developed by Jonathan Haidt and others, popularized in Haidt’s 2012 bestseller, “The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion,” which purports to explain how everyone — liberal or conservative — is moral, just in different ways. As an explanation of liberal/conservative differences, the theory aims to shove aside decades of earlier research on a wide array of different distinguishing factors, which were first comprehensively brought together in the 2003 paper “Political Conservatism as Motivated Social Cognition,” by Jonathan Jost and his co-authors.

Two of those factors are particularly salient in regards to group prejudice, and were highlighted in John Dean’s 2006 bestseller, “Conservatives Without Conscience“: Right-wing authoritarianism (RWA), which reflects ideological commitment to tradition, authority, and social convention; and social dominance orientation (SDO), reflecting commitment to group-based dominance and social inequality.

As the George W. Bush era ended, and Barack Obama and John McCain competed over who could do a better job of working across the aisle, the public mood was ripe for a supporting theory that could help rehabilitate conservatism’s image, and MFT did just that. It posits a small set of distinctly different moral concerns, each correlated with distinctly different emotions — harm with anger, sanctity with disgust, etc. — that Haidt analogizes to tastes.

Liberals are primarily sensitive to two such moral “tastes,” Haidt argues, one concerned with harm versus care, the other with fairness and reciprocity. Haidt has called these values “Millean,” referring to John Stuart Mill’s classic “On Liberty.” Liberals have erred, Haidt claims, in believing that’s all there is to morality. Conservatives respond additionally to three other moral “tastes,” Haidt argues, which have to do with the laudable aim of binding people into communities: authority/respect, in-group/loyalty, and purity/sanctity. Haidt identifies these with pioneering sociologist Émile Durkheim, providing a simple shorthand that is part of his theory’s appeal.

“A Durkheimian society would value self-control over self-expression, duty over rights, and loyalty to one’s groups over concerns for outgroups,” he wrote in 2008. “A Durkheimian ethos can’t be supported by the two moral foundations that hold up a Millian society (harm/care and fairness/reciprocity).”

It makes for a neat little just-so story, and MFT was widely hailed with the promise that it would “help both sides understand the other, so that policies can be made based on something more than misguided fear of what the other side is up to,” as Haidt put it in 2009.

That outlook was in sync with the country’s dominant mood at the time of Obama’s inauguration. Eight years later, with the election of Donald Trump, things look radically different. What seemed plausible when Newt Gingrich was sitting on a couch next to Nancy Pelosi talking about finding solutions to climate change seems much less so with Gingrich standing by Donald Trump, who has called climate change a hoax invented by the Chinese.

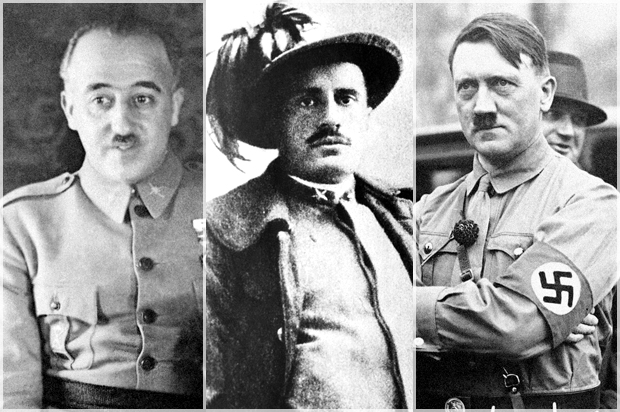

Those binding moralities Haidt celebrates suddenly don’t look so benign when we’re talking about binding together a racial elite and getting rid of the Untermenschen. Nor do conservatives seem to especially value purity while rallying around a foulmouthed, vulgar, self-professed sexual predator.

But it’s not just a matter of appearances. Researchers in the field have not merely poked holes in MFT from several different directions, they have developed better alternative explanations, including a more comprehensive framework for earlier research on authoritarianism. With Trump’s election, there’s more reason than ever to understand how MFT has confused things, and how we can get unconfused by recent research that exposes its flaws.

One reason MFT enjoyed such popular acceptance — despite plenty of evidence against it — was that it told elites what they wanted to hear: Conservatives and liberals were both driven by reason and morality, there was plenty of ground for compromise in the “center,” and so on. Now that elite complacency has been shattered, the time is ripe for a closer look at more plausible if less pleasing stories.

In early 2015, I reported here on two significant developments. First I interviewed Jost following publication of a paper he co-authored, “Another Look at Moral Foundations Theory: Do Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation Explain Liberal-Conservative Differences in ‘Moral’ Intuitions?” The short answer to the question was “yes.” The research showed that conservative “moral concerns” — “in-group, authority, and purity concerns” — were “positively associated with intergroup hostility and support for discrimination,” while at the same time, liberal concerns (fairness and harm avoidance) were negatively associated with the same variables.

Then I interviewed Daryl Cameron about a paper he co-authored, “A Constructionist Review of Morality and Emotions: No Evidence for Specific Links Between Moral Content and Discrete Emotions.” Not only did Cameron’s group of researchers find a lack of support for the inner architecture of Haidt’s theory, separating the moral world into discrete, insular subsets of paired emotions and moral realms, he pointed out that even the seemingly uncontroversial distinction between underlying emotions and moral reasoning was not hard and fast, but rather fluid and context-dependent.

“So, if you’re cut off in traffic, if you’re focused internally, what you’ll notice is an experience of anger,” a supposedly distinct emotion, Cameron told me. “But if you’re focused outward on the world as this happened, you might think, ‘That person is a jerk, that person is morally atrocious,’ because of how he or she is driving,” a simplistic example of moral reasoning.

Those two papers clearly underscored deep problems with MFT, but a new paper goes much further in laying out a roadmap for how to go beyond it: “Replacing the Moral Foundations: An Evolutionary-Coalitional Theory of Liberal-Conservative Differences.” By phone and email, I interviewed the co-authors, Jeffrey Sinn and Matthew Hayes.

“MFT explains liberal-conservative differences as cultural differences, suggesting conservative culture emphasizes community and divinity while liberal culture emphasizes autonomy,” Sinn told Salon. “But MFT offers no reason why these different cultures arise in the first place.” It also “underspecifies,” or fails to account for the entirety of either of them. Evolutionary-Coalitional Theory (ECT) steps up where MFT falls down, not just pointing out MFT’s weaknesses, but also stronger, better ways to make sense of things.

First off, Sinn said, “ECT suggests that the ‘binding morality’ idea underspecifies conservatism. ECT suggests that the laudable binding drive arose because it steeled coalitions against adversarial outgroups.” Thus, the tendency toward “xenophobia and outgroup degradation” within conservative movements “is not a design flaw but an essential feature — it’s a binding and dividing morality.” Which explains the authoritarian element in conservatism measured by RWA.

But that’s not all, Sinn explained. “ECT suggests this defensive or ‘binding’ ethnocentrism blends in practice with a darker orientation specifically motivated to dominate and exploit vulnerable outgroups.” That is known as social-dominance orientation or SDO, he explained, “an orientation MFT completely misses in its representation of conservatism.” There’s also research correlating social dominance with the dark triad behind fascism and demagoguery — Machiavellianism, psychopathy and narcissism — which sheds more light on Donald Trump and how he got where he is today.

But it’s not just conservatism that Haidt’s approach gets wrong, Hayes pointed out. “ECT also asserts that MFT underspecifies liberalism, limiting it to individualistic concern for self-determination. Instead, ECT contends that liberalism reflects concern with a wider world, one that includes all people and extends morality to include the natural world.” This is clearly reflected in liberal thought and language, as it emerged from the Enlightenment, most notably in articulating the idea of universal rights.

Getting both sides of the equation wrong is a recipe for confusion. The distinction between John Stuart Mill and Durkheim is central to Haidt’s just-so story, as Hayes points out.

“MFT limits liberal values to individualistic concerns, preventing harm and ensuring fairness, things that significantly affect individuals but don’t foster a sense of ‘us,’” Hayes said. “MFT thinks of conservatism as broader because the binding motivations extend beyond the individual to include groups (e.g., states, nations, religious groups, etc.), but only when there are other competing groups.”

That qualification goes to the heart of what MFT misunderstands. “ECT argues that liberalism actually reflects a more inclusive, universalizing morality,” Hayes explained. “It’s more inclusive because liberals’ sense of ‘us’ extends to all people, not just those belonging to my town, state, country or religion. ECT also argues that liberal morality is broader in that it extends beyond humanity to include the natural world (e.g., global warming, species extinction).”

The just-concluded presidential campaign offered a textbook demonstration of those points. Liberals celebrated and defended immigrants of all faiths, from all around the world, seeing them all as contributing to a stronger, more robust and more inclusive America. Trump profited from attacking them as rapists and murderers bent on destroying America. Liberals were concerned with global warming both for its impact on the natural world, as Hayes notes, but also for its dire impact on future generations — our childen’s children’s children. Trump dismissed global warming as a Chinese conspiracy, a money-making fraud. For him, it was literally inconceivable to take climate change seriously, either the overwhelming scientific evidence or the moral concerns. And he spoke for large numbers of conservatives in doing so.

This returns us to the problem of how MFT hides conservatism’s dark side.

“MFT seeks to obscure the darker sides of conservatism revealed in the work on both right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) and social-dominance orientation (SDO),” Sinn said. “MFT seeks to repackage RWA as simple in-group solidarity (denying the out-group antagonism) and completely denies SDO as the twin-driver of conservatism. Multiple studies show that the so-called binding foundations are simply RWA and that so-called ‘individualizing’ foundations replicate (the reverse of) SDO.” The only thing new MFT offers is “highlighting the special role of purity in conservatism,” he concluded.

Taking a step back, an even more basic problem comes into view: the fact that the dark side of conservative motivations — most vividly, SDO and the aforementioned “dark triad” — disqualifies them as moral values according to MFT itself. Haidt has defined morality as “any system of interlocking values, practices, institutions, and psychological mechanisms that work together to suppress or regulate selfishness and make social life possible.”

I asked Sinn about this. “Yes, I completely agree,” he responded. “It’s all a semantic game. MFT defines morality as those practices that regulate selfishness and then presumes [that] ideological differences reflect merely different moralities. SDO is an exploitative, power-based motivation not fitting the definition of morality, ergo it cannot be a driver of ideological differences. Sleight of hand. Nothing to see here.”

That sleight of hand may have worked with Obama in the White House, but it clearly doesn’t work in the face of Donald Trump. There is no getting around the fact that Trump’s powerful emotional draw on his conservative base is driven by appeals that unleash, justify and celebrate selfishness and even cruelty, topped off by his own very public “dark triad” behavior.

Some conservatives, to their credit, still regard Trump as anathema, but every era sees some old-line conservatives at odds with whatever new direction conservatism takes. Former Nixon White House aide John Dean, author of the aforementioned “Conservatives Without Conscience,” has been an honorable example of this for quite some time. But the dominant tenor of conservatism is now inextricably bound up in all of Trump’s negative characteristics — characteristics that Haidt’s theory completely ignores or denies.

One further piece of evidence of this was pointed out by Hayes, from a September Winthrop Poll of South Carolina voters.

“The Winthrop Poll was unique in that it examined the role of social dominance orientation in addition to authoritarianism and demographic factors in predicting support for Clinton and Trump,” Hayes said. “The SDO results tell us that support for Trump is related to factors that foster group exploitation; namely, beliefs that some groups are better than others and opposition to efforts that might reduce the inequalities between groups present in the status quo.”

The four-point scale used in the Winthrop survey to measure authoritarian leanings — based on parenting attitudes — is not identical to RWA, but captures similar attitudes. What’s particularly striking is the vast difference between white Clinton and Trump supporters, although the sample of white Clinton supporters was admittedly too small to be considered definitive. (African-Americans routinely score higher than whites on this authoritarianism scale, for reasons still under debate in the social sciences.) The parenting scale went from 1, most lenient, to 4, most strict. While Trump voters as a whole had a mean score of 2.3850, compared to 2.1127 for Clinton voters, white Trump voters scored 2.4019 compared to 1.1262 for white Clinton voters. That’s an indicator of people who come from utterly different worlds — a difference not nearly as visible as race, gender or ethnicity, but just as profound in its own way.

Something similar could be seen with the SDO scale for voters of all races. The poll found “many more Clinton supporters on the low end of the pro-dominance scale. … with only Trump supporters at the highest pro-dominance scores observed.”

“If we want to understand politics in the U.S. today, we need to go beyond demographic factors and also understand how people perceive their relation to different groups,” Hayes said. “Who is one of ‘us’ versus one of ‘them’ means different things to, and carries more importance for, conservatives than liberals. It also has different consequences for people high in RWA versus SDO.”

But noting the impacts is just a starting point, he pointed out. “While I think it’s important that we continue to measure RWA and SDO, it’s also important that we understand who Americans think of as ‘us,’ especially in the aftermath of a very polarizing election cycle. Whether we restore an inclusive sense of ‘us’ that extends to our national borders or instead think of the nation as composed of ‘real Americans’ and ‘them’ will have very real consequences for the nation.

Finally, I asked how ECT might help prepare us to view America’s immediate future, and whether it is better suited for that task than MFT.

“ECT suggests that when people are made to feel insecure they will tend to think in a more us-versus-them mindset and will use ethnically-indexed cues to establish these differences,” Sinn said, meaning “cues that in the ancestral environment were reliable markers of different genetic background – differences of phenotype, language, religion, territory, etc.”

Conservatives, Sinn said, may “never move past a dividing of us-versus-them because this is the deep structure of right-wing thinking.” But then he added, “The voting demographics of the last election, the rural-urban and the education divide, suggest that there is something about urban living and higher education that broadens the sense of self or the number of groups one belongs to, such that the ethnocentric pull weakens.”

Hayes was a bit more clear-cut, and possibly even optimistic. “ECT can help us understand (and maybe help bridge) the liberal-conservative divide because it helps clarify the difference between liberal and conservative definitions of ‘us.’”

At the very least, it can help us stop fooling ourselves. When it comes to moral foundations, Trump doesn’t have any that are worthy of the name. That needs to be made clear to anyone who yearns to side with him. There’s no hiding from that anymore behind a psychological or sociological just-so story.

MFT argues that we must treat everyone’s moral conclusions as equally valid, but is based on a false claim of moral equivalency. Still, the striving for inclusion and equal treatment are fundamental to how liberals see the world. Conservatives may delight in warring against liberals, but liberals will always want to make peace. Neither basic orientation is about to change. What progressives and liberals can change is how we think about making peace. We can strive to respect and understand conservatives’ moral orientations and concerns without feeling any need to agree with their immoral conclusions. Once we’re clear on that, we can fight like hell for a just and lasting peace.