UPDATE: After this article was published, Salon learned that Object No. 1 has encountered some difficulties and will not appear in this summer's Venice Biennale, but there are plans to feature it at some future date.

Kazimir Malevich is everywhere, but perhaps you don’t realize it. Yasmina Reza’s famous play "Art" has just been revived in London: It’s the story of what happens among a group of friends when one of them buys an all-white painting for an outrageous sum of money. Though the artist of the work is fictional, the work it parallels is not. Malevich’s 1918 "Suprematist Composition White on White," looks just like the title suggests: white, with an offset square inside in a slightly different white. (I even wrote about it in my novel about art theft.)

But it’s not just "White on White" that is making headlines. This summer, the Venice Biennale will host a multifaceted, symbolic layer-cake of a project that features Malevich’s other most iconic work: "Black Square" (1915). The new installation, called "Object Number 1," envisions a reconstruction of Vladimir Lenin’s tomb inside a three-dimensional cube rendition of "Black Square" — or rather, “black cube.” “Object Number 1” was the mysterious term used by Soviet leaders to describe Lenin’s body, after his death in 1924. His tomb became, and for some still is, a pilgrimage destination. In life and in death, he became the icon of Communism, as recognizable (and collectible) as the hammer and sickle, with likenesses gracing homes the way Christ and saints did before Communism marginalized religion, and today is available in plasticized souvenirs.

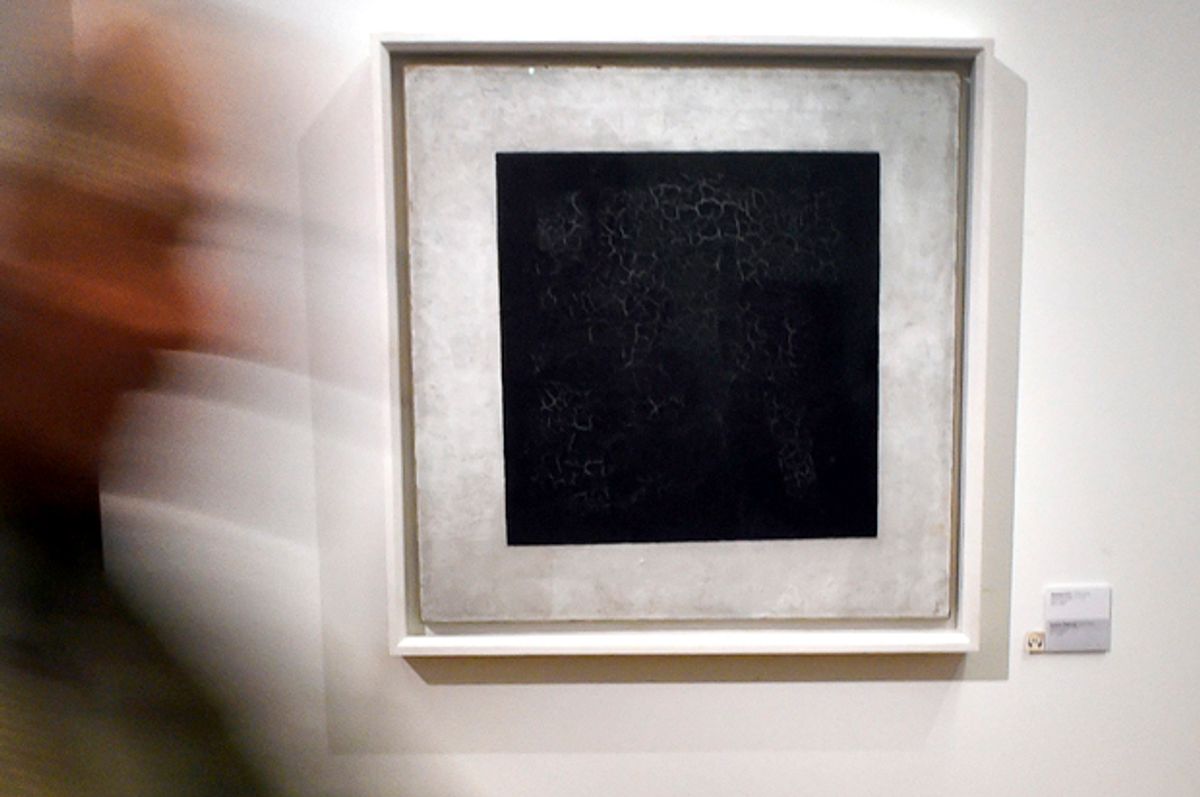

"Black Square" was conceived as the ultimate negation of the icon and, in doing so, it became a new form of icon. A black square inside a white square, the black is now beautifully textured (some might say ruined — it was poorly stored for decades) due to craquelure (the cracks made by the expansion and contraction of the pigment due to time and humidity), but originally it was smooth and matte. Absolute black, like absolute white, is a nothingness. To be precise, absolute white is a nothingness (absence of color), absolute black is everythingness (all colors combined). But in both cases, there is no form. It has been called “the zero point of painting.” It was first shown in the “Last Futurist Exhibition” in 1915, which is important, because Futurism, the largely Italian movement spearheaded by Tommaso Marinetti, promoted the need for a complete break from past, history and traditions, and the development of a wholly new type of art. For Marinetti, this included a spookily Fascist call to destroy all museums and libraries, to wipe the slate clean. But for Malevich, who would develop a variant on Futurism, which he dubbed Suprematism, the rejection of traditional, formal art was about stating independence and in keeping with the revolutionary mood of the time.

"Black Square" is, itself, despite its aesthetic simplicity, packed with layers of complexity, quite literally. In 2015, X-rays revealed not one, but two hidden paintings beneath. The bottom of the layer-cake, the original image on the canvas, is described as a “Cubo-Futurist” colorful work, a style with which Malevich experimented circa 1910, melding the Cubist technique of breaking down an image into shuffled geometric forms with Futurist concepts of breaking from the past and striving for entirely new aesthetic vocabularies. On top of that painting, but beneath "Black Square," what has been called a “proto-Suprematist” composition, also colorful, was revealed. As a movement, Suprematism rejected formal art in favor of extremely basic, monolithic geometric forms, of which "Black Square" is the textbook example. Largely erased from the white space around "Black Square," conservators also found a bit of text in Malevich’s hand, which reads “Negroes battling in a cave.” This has been interpreted as the concept behind "Black Square," perhaps inspired by an 1897 painting by a French writer, Alphonse Allais, entitled “Negroes fighting in a cellar at midnight,” a disgraceful racist joke about the concept of layering black-on-black.

A new feature-length documentary film about the art of the Russian Revolution from Foxtrot Films, "Revolution: New Art for a New World," directed by Margy Kinmonth, debuts in theaters across the United States starting on the centennial of the beginning of the revolution, March 8. It begins with a quote from Lenin himself: “Art is the most powerful means of political propaganda for the triumph of the socialist cause.” This idea was nothing new — during the Counter-Reformation of the 16th century, the Catholic Church considered art to be a key tool in both propaganda against the threat of Protestantism, and also in luring back wavering Catholics by offering, through art, a more personal, meditative and visceral experience of religious artwork. But Russian art before the time of Lenin had been about formal art, academic (which has long been synonymous with “safe” and “boring” and “bloodless”) works that did nothing new. When revolutionaries occupied the Winter Palace to launch the revolution, they slashed portraits of the czar and his family, all made in a traditional style. They wished to deface the idea of the czar, but might as well also have been attacking the tradition that nurtured the artistic style. “The academy is a moldy vault in which art flagellates itself,” Malevich said. Because the Imperial Academy of Art was linked to the czar, turning against the traditional, formal art it taught was a revolutionary political act.

Lenin encouraged the building of new sculptures, many out of cheap materials like clay and destined not to last long, to honor revolutionary heroes (many from other revolutions, like the French, since Russia didn’t have enough heroes yet to go around). Abstract art became a calling card. A train was decorated with abstract paintings on its exterior, and traveled as a mobile art exhibit, hosting lectures inside its cars.

Inspired by this movement, Malevich wanted something entirely new, a break from all this. He and his associates would throw form out the window, resorting instead to geometric shapes and blocks of color. He wanted to paint ideas, not existing reality but rather an idealistic way the world can be structured (though the idealism of socialism worked better in theory than in practice, as history would prove).

Which brings us back to "Object Number 1." What happens when the fascinating Madrid-based digital technology firm Factum Arte (they specialize in extremely high-quality 3D digital scans of art and monuments, and can also print museum-quality reproductions of them) teams up with Grad (Gallery for Russian Arts and Design) and the architectural firm Catling de la Pena?

The idea is to meld the icons of Lenin’s tomb and his embalmed body with Malevich’s painting, entombing the tomb within it. According to a press statement, “Encased within the sarcophagus will be a sculptural rendering of Lenin made using a process of depth-mapping.” Visitors will walk into the black cube, which will float along the Zattere in Venice. Inside, they will find a reconstruction of the original tomb of Lenin, as well as a 60-seat amphitheater in which to sit and contemplate the rising of the proletariat (or to check your Facebook feed, whatever you’re into). The centerpiece of the tomb will be a life-size, 3D-printed version of Lenin’s body, but this will be visible only from one angle — circle around and the body will appear to be a black nothingness. A quote, attributed to Nietzsche, comes to mind: “Whoever fights monsters should see to it that, in the process, he does not become a monster. And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.” At the Biennale, "Object Number 1" will allow you to physically step into the abyss, the iconoclastic, abstract icon of "Black Square" given three dimensions. Once inside, you can look at the relic of Lenin’s body and see that it, too, is an abyss, only whole from one angle, a void from another.

Malevich had a poetic streak in his pen, not just his brush. He said of "Black Square," “It is from zero, in zero, that the true movement of being begins. . . . It is meant to evoke the experience of pure, non-objectivity in the white emptiness of a liberated nothing.” Of Suprematism, he wrote:

I have broken the blue boundary of color limits, come out into the white, beside me comrade pilots swim in this infinity. I have established the semaphore of Suprematism. I have beaten the lining of the colored sky, torn it away, and in the sack that formed itself, I have put color and knotted it. Swim! The free white sea, infinity, lies before you.

A rousing call to a revolution in art that echoed, inspired and was inspired by the revolution in arms. Malevich liked to display "Black Square" in the upper corner of a room, where a traditional Orthodox religious icon, say of the Virgin Mary, would normally reside in Russian homes. This was an aggressive act, the obliteration of religion, akin to the Communists' complete detonation of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow. Black square, white on white. New formless icons to strike down the icons of old, and then become icons themselves.

Shares