Earlier this year, President Trump denounced the desecration of Jewish cemeteries. But he has said almost nothing about the murder of a black New Yorker last month by a racist military veteran.

All 100 members of the U.S. Senate signed a letter condemning bomb threats against synagogues and Jewish community centers, which were eventually traced to a teenager in Israel. We haven’t heard a similar expression of concern over the four American mosques that were burned by vandals in the first two months of 2017.

Why the double standard? Some observers have suggested that Trump is more attuned to anti-Semitism than to other forms of bigotry because his daughter and son-in-law are Jews. Others point to Trump’s immigration orders and to his earlier threats to bar Muslims from the country, which have made Islamophobia seem less reprehensible — and, possibly, more permissible — than prejudice against Jews.

But I’ve got a simpler explanation: Jews are white.

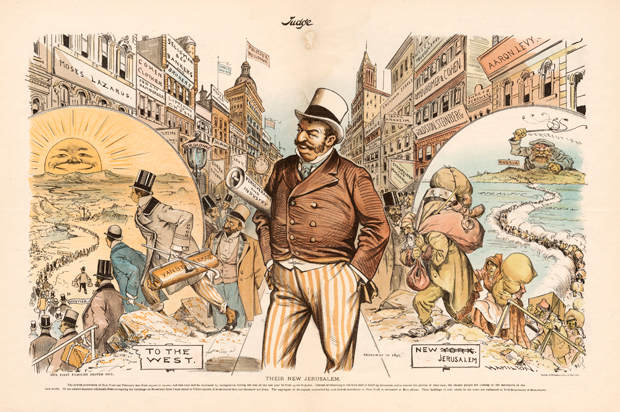

For most of American history, that wasn’t the case. Jews were a separate race, as blacks and Asians are today. But over time Jews became white, which made it harder for other whites to hate them.

That’s the great elephant in the room, when it comes to the tortured subject of race in America. The word “race” conjures biology, a set of inheritable — and immutable — physical characteristics. But it’s actually a cultural and social category, not a biological one, which is why it changes over time.

Until the 1940s, Jews were recorded as a distinct racial group by American immigration authorities. But many non-Jewish whites also believed that Jews shared traits with the most stigmatized race of all: African-Americans.

In his 1910 book, “The Jew and the Negro,” North Carolina minister Arthur T. Abernathy argued that the ancient Jews had mixed with neighboring African peoples. Jews’ skin color lightened when they moved to other climates, Abernathy wrote, but they still bore the same eye shapes and fingernails (yes, fingernails!) as blacks.

Both groups were disposed to sexual indulgence, Abernathy warned, a recurring theme in American racism. “Every student of sociology knows that the black man’s lust after the white woman is not much fiercer than the lust of the licentious Jew for the gentile,” Georgia politician Tom Watson wrote in 1915.

In the North, meanwhile, white racial anxieties about Jewish college students led to quotas that limited their numbers. “Scurvy kikes are not wanted,” read a poster hung on one campus in 1923. “Make New York University a White Man’s College.”

For their own part, Jews couldn’t agree if they were a race or not. Some of them warned that a separate racial classification would inevitably link them to blacks, diminishing Jews in the eyes of other Americans. But others held tight to the racial idea, which could help make the case for a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Yet with the rise of Nazism in Europe, which was premised on Jewish racial inferiority, Jews in America stopped identifying as a race. “Scientifically and correctly speaking, there are three great races in the world: the black, yellow, and white,” a booklet distributed by the Anti-Defamation League declared in 1939. “Within the white race all the sub-races have long since been mixed and we Jews are part of the general admixture.”

After World War II, most white Americans quietly welcomed Jews into their “admixture.” Newspapers and social scientists referred to Jews as members of a religion, ethnicity or culture. But they were not called a “race,” a word that conjured up Adolf Hitler and his effort to eliminate them.

During these same years, the struggle against Nazism overseas helped jump-start the campaign for African-American civil rights at home. But blacks’ status as a separate race remained, as James Baldwin noted in a biting 1967 essay about African-Americans and Jews.

Blacks were tired of Jews telling them that the Jewish experience of prejudice was “as great as the American Negro’s suffering,” Baldwin wrote. The claim ignored racial realities, Baldwin wrote, and it fueled anti-Semitism in black communities. ”The most ironical thing,” Baldwin wrote, “is that the Negro is really condemning the Jew for having become an American white man.”

That’s not an option for African-Americans or for other nonwhite racial groups in America. (It’s worth noting that the racial status of Hispanics is ambiguous: Some identify as white, some as black and many as neither.) These categories are cultural creations, too, not biological ones. When Sonia Sotomayor joined the Supreme Court in 2009, news headlines hailed her as the first Hispanic justice on the court. Yet when she was growing up in the Bronx in the 1950s and 1960s she was Puerto Rican rather than “Hispanic,” a term that did not enter our racial lexicon until the 1970s.

Let’s be clear: Race exists. But it exists in our minds, not in our bodies. In our homes and schools, we need to teach the next generation of Americans to resist the false doctrine of inherent racial difference. Then, and only then, will they truly recognize everyone as part of a single race: the human one.