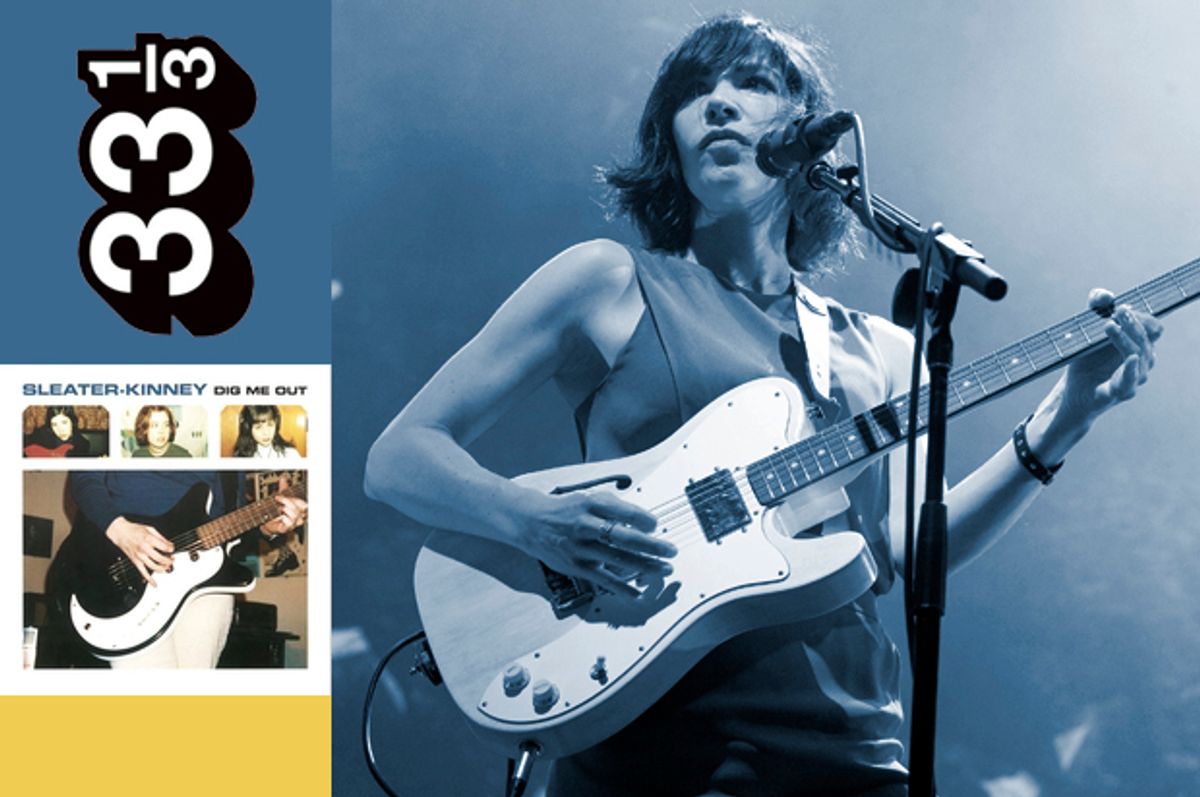

The cover of Dig Me Out provides a lens into how Sleater-Kinney imagined themselves as the album was about to be released in April of 1997. At first glance, it’s a simple cover comprised of four photographs: three small portraits of the band members line the top and a larger close-up of a torso playing a guitar occupies the rest of the frame. The portraits are snapshots taken during a practice session in Weiss’s basement: Brownstein is looking up from her red SG Gibson, Tucker is looking away, and Weiss is drumming with headphones. In the portraits, each woman appears to have been caught in the middle of a thought, not having welcomed the photographer’s gaze; they seem almost annoyed to have been interrupted. Weiss took the large photograph that shows Brownstein’s headless body playing [producer John] Goodmanson’s Jerry Jones Danelectro guitar in the live room at John and Stu’s Place; a Black Sabbath poster peeks out in the back. The name of the band and the album crown the very top in all caps. At first glance, the cover simply declares that this is a group of musicians who prioritize playing over elaborate sleeve art and logos. It almost feels like a haphazard assemblage of image and text. But, as with so much else with Sleater-Kinney, nothing is arbitrary.

The cover of Dig Me Out makes a supporting claim in the band’s case against gender hierarchies implicit in music making. In its design, it’s a take-off of The Kinks’ 1965 album The Kink Kontroversy. The layouts are identical, with the exception that The Kinks had a fourth member and thus a fourth portrait lining the top. Weiss had thought of the idea. “The Kinks are one of my all-time favorite bands and they were revered,” she said. “It was fun to play with that idea of what makes a revered band. And we could be that, too!” On the cover of Dig Me Out, where in place of The Kinks they substituted their own portraits and their own guitars, Sleater-Kinney suggested that three women could embody a rock band (and play guitars and drums) all the same. While they had presented a similar challenge to rock stardom on Call the Doctor’s “I Wanna Be Your Joey Ramone,” the cover of Dig Me Out declared that Sleater-Kinney saw themselves as musicians on a par with The Kinks. “I liked toying with the idea that we didn’t have any limitations, that we could be that band, that people could talk about us like we matter, and that what we’re saying is important,” Weiss elaborated. “But the idea of being heroic is often not presented to women. Women are often seen as motherly and nurturing. We wanted to be heroic, scary, edgy, and challenging.” Heroism is important and, for Weiss, it’s a trait ascribed to the legions of esteemed rockers like The Kinks—most of them men. To place Sleater-Kinney among them was to question women’s exclusion from the canon, an exclusion that female musicians had long been pushing up against but that nevertheless continued to prevail in the 1990s.

But more than just the cover, Dig Me Out as a whole can be considered a rejection of the categories that were frequently imposed on female musicians. Nothing about the album nurtures or seduces the listener. “It was really intense, a very personal album that got at some of the things we faced as women in this band,” Tucker told me. Although women were certainly visible in popular culture in the late 1990s, performers like the Spice Girls and Celine Dion reinforced gender roles rather than dismantled them. There was little room for women who stepped outside brackets like “sexy” or “sentimental” or those who performed social defiance like their male counterparts. Performers who did were rarely taken seriously as musicians, as Sleater-Kinney found time and again when they interviewed with mainstream presses and toured across the United States. The riot grrrl movement had chipped away at the gendered conceptions of culture in the early 1990s, but the climate for women in music seemed just as grave in the second part of the decade.

When Dig Me Out was released in the spring of 1997, responses from fans reiterated just how desperate American audiences had been for a band like Sleater-Kinney. Many were hungry for female musicians who undermined gender hierarchies in music making—what Olympia’s space had provided for Tucker and Brownstein. “From the way people responded to it,” Weiss said, “I know that it had cultural weight as an important record. It seemed there was a feeling of necessity when it came out.” The immediate acclaim of Dig Me Out among listeners made the struggles it took to make the album seem worthwhile. “People lost their minds,” Julie Butterfield remembered. “They just loved the album.” Critics, too, loved the album and several heavyweights soon rallied behind the band.

The most important change set in motion by Dig Me Out was that Sleater-Kinney began to be revered as rock stars. When I spoke with John Goodmanson, he shared with me an interesting anecdote about the Jerry Jones Danelectro guitar that Brownstein is shown playing on the album cover. “When I show up with that guitar, people freak out and want to get their pictures taken with it,” he narrated. “When I was working with the Los Campesinos! guys—there’s a lot of them—they all had to get their picture taken with that guitar.” The myth of the Danelectro resembles the one of Abbey Road where The Beatles were once photographed for an album cover. Fans flock to Abbey Road to recreate the scene of the legendary crossing, just like they do to photograph themselves with the guitar that appears on the cover of Dig Me Out. Both of these signifiers capture the imagination of fans because they were once embodied by those perceived to be heroic. That’s to say that with Dig Me Out, Sleater-Kinney had breached a world where they could be heroes.

Shares