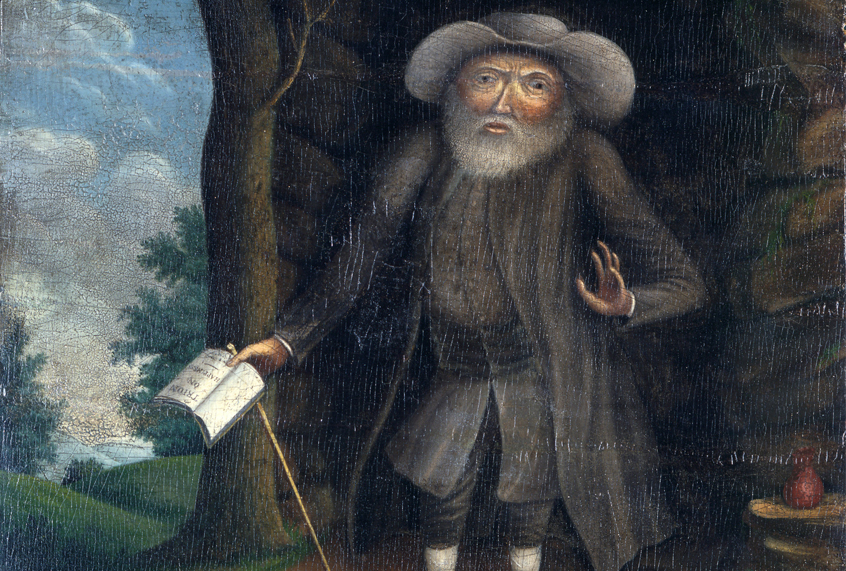

The Quaker dwarf Benjamin Lay (1682-1759) was the first revolutionary abolitionist. He demanded an end to slavery and therefore radical change in all societies where it had a significant presence, and he anchored abolition in a new way of life, without human and animal exploitation, based on the “innocent Fruits of the Earth.” He lived in a cave, ate only fruits and vegetables, championed animal rights, and refused to consume any article produced by slave labor. The first person to call him a revolutionary was Benjamin Rush, Philadelphia physician and signer of the Declaration of Independence, in 1790, the beginning of a decade that would see the Atlantic in flames, from Paris to Belfast to Port-au-Prince. Rush explained that Lay sowed “the seeds of a principle which bids fair to produce a revolution in morals, commerce, and government, in the new, and in the old world.” Lay the commoner would have liked the planting metaphor, and Lay the sailor would have liked the transatlantic reach.

Born to a Quaker farm family in Copford, a small village in Essex, England, Lay moved as a young man to London and went to sea, relocated to Barbados at age thirty-six, and moved to Philadelphia at age fifty. He entered an urban trade and then a global seafaring culture between roughly 1700 and 1714, became a convinced abolitionist after his encounter with slavery between 1718 and 1720, and devoted himself to a new kind of commoning from the 1730s through the late 1750s. To a foundation of Quaker radicalism he added the egalitarianism and cosmopolitanism of seafaring culture, the life-and-death struggles of African America, and the environmentally friendly ways of vegetarianism. He talked with and learned from enslaved people in Barbados. He fed the hungry and preached an end to slavery, earning the wrath of the master class. He denounced ministers – Quakers and others – who did not live up to his standards. He spoke truth to power, shaming and defying slave traders and keepers. He dared to live in a new way based on an ethical relationship to all living things. He applied evolving radical principles to all aspects of his life, changing himself as he changed the world. He chose what he considered the best practices from multiple social worlds as he tried to create a new one. He wrote and lived an eighteenth-century “theology of liberation.”

Lay is little known among historians. He appears occasionally in histories of abolition, usually as a minor, colorful figure of suspect sanity. By the nineteenth century he was regarded as “diseased” in his intellect and later as “cracked in the head.” To a large extent this image has persisted in modern histories. Indeed David Brion Davis, a leading historian of abolitionism, condescendingly called Lay a mentally deranged, obsessive “little hunchback.” Lay gets better treatment by amateur Quaker historians, who include him in their pantheon of antislavery saints, and by the many excellent professional historians of Quakerism. He is almost totally unknown to the general public.

Lay was better known among abolitionists than among their later historians. The French revolutionary Jacques Pierre Brissot de Warville gathered stories about him almost three decades after his death, during a visit to the United States in 1788. Brissot wrote that Lay was “simple in his dress and animated in his speech; he was all on fire when he spoke on slavery.” In this respect Lay anticipated by a century the abolitionist leader William Lloyd Garrison, who was also “all on fire” about human bondage. When Thomas Clarkson penned the history of the movement that abolished the slave trade in Britain, in 1808, a moment of triumph for that country, he credited Lay, who had “awakened the attention of many to the cause.” Lay possessed “strong understanding and great integrity,” but was “singular” and “eccentric.” He had, in Clarkson’s view, been “unhinged” by cruelties he observed in Barbados between 1718 and 1720. When Clarkson drew his famous graphic genealogy of the movement, a riverine map of abolition, he named a significant tributary “Benjamin Lay.” On the other side of the Atlantic, in the 1830s and 1840s, more than seventy years after Lay’s death, the American abolitionists Benjamin Lundy and Lydia Maria Child rediscovered him, republished his biography, reprinted an engraving of him, and renewed his memory within the movement.

Lay is not the usual elite subject of biography. He came from a humble background and was poor most of his life, by occupation and by choice. He lived, he explained, by “the Labour of my Hands.” He was also considered a philosopher in his own day, much like the ancient Greek Diogenes, the former slave known for speaking truth to power. (He refused Greek nationality and insisted that he was, rather, “a citizen of the world.”) Lay lived a mobile, far-flung life, in England, Barbados, Pennsylvania, and on the high seas in-between, all of which shaped his cosmopolitan thinking. Unlike most poor people, he left an unmediated record of his ideas, most significantly in his own book, “All Slave-Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates,” a rich and remarkable body of evidence by any measure.

A central tactic in Lay’s militant attack on slavery was the guerilla theater he practiced against slave-owners. Lay advocated incessantly for emancipation, in some cases on behalf of specific individuals he knew. One such person was a “negroe girl” — her name has not survived in the evidence — who was owned by Lay’s Quaker neighbors in Abington, Pennsylvania. Lay argued repeatedly with the man and woman about the iniquity of keeping slaves, insisting that the girl be freed, but to no avail. The couple not only kept her in bondage; they justified the practice. Lay explained to them the “wickedness” of the slave trade, emphasizing how it separated children from their parents. Soon after, Lay encountered the six-year-old son of the couple a short distance from their farm. He invited him to his cave about a mile away and entertained the boy all day inside, out of view.

When evening came on, Lay observed the boy’s father and mother running toward his dwelling. He advanced and met them, “enquiring in a feeling manner, ‘what is the matter?’” The parents replied in anguish, ‘Oh Benjamin, Benjamin! our child is gone, he has been missing all day.’” Lay listened with sympathy, paused, and said, “Your child is safe in my house.” Then he explained why he was there: “You may now conceive of the sorrow you inflict upon the parents of the negroe girl you hold in slavery, for she was torn from them by avarice.” Lay expressed a simple, profound message central to Quakerism and indeed to all Christianity: do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

Lay’s radicalism was a rope of five strands: he was a Quaker, philosopher, sailor, abolitionist, and commoner. As a free thinker he drew on a wide variety of books and intellectual traditions, combining them creatively to serve his own values and purposes. He was first and foremost an antinomian radical — someone who believed that salvation could be achieved by grace alone and that a direct connection to God placed the believer above man-made law. Lay combined Quakerism with abolitionism and other radical ideas and practices that were uncommon for his time and rarely thought to be related: vegetarianism, animal rights, opposition to the death penalty, environmentalism, and the politics of consumption. For Lay these beliefs and practices were all part of a consistent, integrated, ethical worldview — one that could save a planet desperately in need of salvation. He showed that multiple forms and traditions of radicalism could all be part of the same consciousness. He believed that abolition must inform a revolutionary revaluation of all life, premised on a rejection of the capitalist values of the marketplace. Benjamin Lay was, in several ways, a curiously modern man whose story has never been fully or properly told. He is a radical for our time.

In the aftermath of numerous successful abolition movements, now that almost everyone agrees that slavery was, and remains to this day, morally wrong, it is not easy to recover the profound hostility Lay encountered for espousing antislavery beliefs in the early eighteenth century. Lay himself noted how people flew into rages when they heard him speak against bondage. They ridiculed him; they heckled him; they laughed at him. Many dismissed him as mentally deficient and somehow deranged as he opposed the deep “common sense” of the era. The scorn was based in economic interest and racial prejudice but also in bias against him as a little person. Each reinforced the other in cruelty and rancor.

As both an abolitionist and a dwarf, Lay withstood pressure and constant derision for decades, but he never sank, declined, flinched, or retreated. At the same time his determination and conviction made him an awkward and difficult person, to say the least. He was loving to his friends, but he could be a holy terror to those who did not agree with him. He was aggressive and disruptive. He was stubborn, never inclined to admit a mistake. His direct antinomian connection to God made him self-righteous and at times intolerant. The more resistance he encountered, or, as he understood it, the more God tested his faith, the more certain he was that he was right. He had reasons both sacred and self-serving for being the way he was. He was sure that these traits were essential to defeat the profound evil of slavery.

The ill will expressed toward Lay in Barbados and Pennsylvania came from both above and below — from political and religious leaders and from ordinary people, all of whom supported the institution of slavery in one way or another. To make this point, Lay’s biographer Roberts Vaux quoted Rome’s great lyric poet, Horace, of whom Lay would certainly have approved, as he loved the writers of antiquity:

The just man who is resolute

will not be turned from his purpose

either by the rage of the crowd or

by an imperious tyrant.

It took fortitude and courage to face the kind of opposition that confronted Benjamin Lay over the last forty years of his life. Fortunately for him, and for posterity, those virtues were never in short supply. He demonstrated the power of saying no to slavery. His life is a story of fearlessness in that cause.