My father and I were very close: we shared the same birthday and people said I took after him. He was a role model, confidant and mentor who supported and challenged me, talking me through problems and piercing through any of my self-deceptions with scientific precision. Even after leaving home for college, I would consult him on personal matters and his brutally honest opinion generally guided my decisions. After his death I realized to what extent I had depended on his sage advice. It took me a long time to disentangle the person he wanted me to be from the person I had to become on my own.

I loved my father’s adventurous spirit, his inquisitive and critical mind and his great capacity for enthusiasm. He was interested in so many things and his passion was contagious. My fondest memory is probably of him telling stories. He was a masterful storyteller who could transform a boring highway into a monster’s endless tongue, pulling our family car into a treacherous adventure. I remember a story he began during a trip to Mexico as we lay in a tent, recovering from sunburns. His wildly imaginative story stretched on over several days, ending with a drunken old man sitting under an oak tree on a hilltop. He never ended the story even though, for years to come, my brother and I begged for him to continue. My father was also a fabulous reader who introduced us to “The Hobbit,” “Watership Down” and “The Call of the Wild.” He gave each character such a unique voice and accent that I can still hear his lisping version of Gollum in Tolkien’s trilogy. My father could be very funny, both sarcastic and goofy. He was a big Monty Python fan and came up with his own silly walks or hilarious outfits and hairdos to make us laugh. He knew how to throw a party, loved cooking and entertaining. We would often assemble in the kitchen to watch him make a bechamel sauce or his unbeatable zabaglione dessert.

Now at 52, I am older than my father was when he was killed and I have lived more than half of my life without him. In the years following his death, as I tried to forget what had happened to him, I feared forgetting him, too. Sure enough, he is not as present as he once was, but as a parent myself now, I find his ways often coming back to me and I seem to recognize bits of him in my own son. I know that if I ever need to summon him, Keith Jarrett’s soulful “Kölner Concert” recording can transport me right back to the concert hall where my father and I heard the jazz pianist play more than 40 years ago. Or I sit down at the piano myself and imagine him listening, urging me to play just one more piece.

As close as I felt to my father, I didn’t end up sharing his fascination with science. I’m more of a humanist, but I respect the scientific approach and recognize that science is key to solving our planet’s most urgent problems. In retrospect, I regret not having listened more to his explanations of the natural world. While he described the northern lights he witnessed on research trips to Alaska and Norway as highly charged particles released by solar storms colliding with the earth’s atmosphere, I would envision a paint brush swooping across an enormous canvas. Finally, I experienced this auroral display myself—exactly a week after the shootings and a day after the memorial service for the victims. As my mother and I were taking an evening walk down an alleyway in our neighborhood, several cawing crows drew our attention up toward a fabulous spectacle of reds and greens in the sky. Our first reflex was to laugh and to interpret this lightshow as a cosmic farewell. Undoubtedly, my father was smiling down at us, mocking us for being so superstitious. Yet even the scientific community drew a connection and regarded the aurora over Iowa as a “fitting tribute” to colleagues who had spent years studying the phenomenon. Today, a plaque outside the so-called “Aurora Room” in the physics department is dedicated to the memory of its four victims: Christoph K. Goertz, Dwight R. Nicholson, Robert A. Smith, and Linhua Shan.

The mass shooting of November 1, 1991, happened while I was in graduate school in Austin, Texas. I had just been home a week earlier for the Thanksgiving break during which my father and I had a long, difficult conversation about my studies. I was having doubts about continuing beyond a master’s degree and he was very frustrated by my desire to give up. It was a heated discussion to be continued over the Christmas holiday which, of course, never came to be. That unfinished conversation may have been part of the reason I continued my studies; I couldn’t let him down. It took me several years to complete my dissertation because, in a way, it was connected with my father’s death and completing it would also mean moving on, which I still wasn’t ready to do at that point. One night, however, my father came to me in a profound dream: I was following him through ruins of a charred city, hurrying to keep up with him. I would lose sight of him whenever I stopped to type a few pages on a typewriter in my trench coat pocket and would then rush to catch up with him again. This happened several times until my father finally said, “Karein, you don’t need to follow me. Just stop and finish writing. Don’t worry, you will always find me.” I completed my dissertation within a few weeks of that decisive dream.

I heard about the killings on NPR while driving home: “Gang Lu, 28, a graduate student in physics from China, reportedly upset because he was passed over for an academic honor, opens fire in two buildings on the University of Iowa campus. Five University of Iowa employees are killed, including four members of the Physics Department; two other people are wounded. The student fatally shoots himself.” It was the top story on the 5 o’clock news and just over an hour after the shootings, so they hadn’t released the names yet. When I heard that it had taken place in the physics department at the University of Iowa and that several were dead, I experienced momentary panic, but calmed myself down with rationalizations: the department was large, I reasoned, and the chance that my father would be among the victims was more unlikely than not. I tried calling home and initially no one answered. Eventually a stranger picked up and called for my mother, who didn’t come to the phone. I could hear that there were a lot of people in the house and began suspecting the worst. I don’t remember who told me that my father had been killed, maybe it was mother. When I broke down at home, my dog came and did a wonderfully primal, protective thing: she quietly lay down on top of me. Her weight eventually calmed me. Years later, when I had to put her down, I remembered that moment.

I then became extremely calm and methodical, calling the German Department, where I worked as a graduate teaching assistant, letting them know that I would not be coming in the next week. Then I called the airlines to book a flight to Iowa City. When they said they would need a death certificate to warrant a special airfare rate, I told them to check the front page of the next day’s newspaper. Then I left messages on the answering machines of close friends, asking them to come over as soon as they could. Eventually they started flocking in and the apartment was filled with people. They cried with me, but we also laughed. In the middle of the night, we all took a walk. It was a clear night and I felt calmed by the sky and familiar Orion. For a moment things were put in perspective: no matter what happens down here, whether we feel like our world is falling apart, the stars and planets are there, unmoved and unchanged.

I did not have a TV, so my only media exposure to what had happened was through the radio news, which I think I listened to once or twice then turned off. The next day, when I was in the airport, I saw the pictures of the killer and victims on the front page of the newspapers. It completely unhinged me. My housemate who brought me to the airport had packed my things into a bag that seemed to have a million pockets. I kept frantically rummaging through them, trying to find something. That bag became an obsession for me during the flight. I think it distracted me from thinking about the larger issues at hand.

The immediate aftermath of the shooting is a blur of fragmented memories. Lots of flowers, cards, people stopping by the house. A huge memorial service organized by the university which I attended wearing my father’s oversized shoes. Seeing his body in the hospital morgue and amazed to find hardly a sign of his violent death. Touching him to comprehend what “dead” is. It must have been much later, my brother and I going to the room where the shootings took place to search for traces. Sorting through my father’s belongings in his office, finding poems he’d written, letters, notebooks filled with mathematical formulas.

My mother, brother and I retreated into our separate emotional orbs. We were each too wrapped up in our own shock to be able to care for each other. My mother responded with much more anger than I did, wanting to find who was to blame for what happened and launching herself into anti-gun lobbying. I vaguely remember the two of us appearing on the local television news, making a statement against the easy accessibility of handguns. She organized a successful boycott against local sporting goods stores that sold handguns. My grandmother, recently widowed, had been staying with my parents at the time. She was inconsolable about losing her youngest son and went around the house asking, “Why didn’t he just kill me?” Half a year later, she committed suicide. This was something I have never really processed.

I went into counseling shortly after returning to Austin and graduate school. The sessions were immensely helpful, although I do not remember much of what went on. It was comforting to have a safe, familiar place to talk about all of the things that were coming up inside that I didn’t understand. I often could not remember what year it was or completely phased out and the therapist helped me understand that this was OK, that my mind was taking its time to sort through thoughts and feelings, blocking things out and letting them back into my awareness slowly and incrementally. Since I will never know, I forced myself to believe that my father died immediately: no pain, just a mere instance of surprise, hardly enough time even for regret.

Five years after the shootings, we were still reeling from the after-effects of this rupture, trying to regroup as a family, but still feeling disoriented and fragmented. My mother sold our family home, left Iowa City and embarked on a new career. She was going through chemotherapy for a cancer she believed was triggered by the traumatic experience of my father’s murder. I was finishing my graduate studies, struggling to write a dissertation on the transmission and embodiment of traumatic memories across generations in Holocaust memoirs and fiction. After a turbulent beginning that coincided with Hurricane Andrew, my brother was well into his architecture studies at Miami University. In a way, the city’s disaster recovery mode mirrored his own strategy for dealing with inner turmoil. Rebuild, move on.

Ten years later, my mother had moved back to Germany. Her cancer was in remission, she was working as a Feldenkrais and Alexander Technique practitioner in Berlin, and launched herself into the all-consuming project of renovating an old house in Italy. I had married, held a teaching position at the University of Michigan Residential College, was leading study-abroad trips to Berlin, and was fully engaged in my career. My brother was finishing up his studies and beginning to work in an architectural firm in Miami.

Today, my mother is a vibrant, physically and intellectually active woman with a large network of friends and many different interests. She is an inspiration to me in so many ways: a model of aging well and living life with gusto. I still teach at the university and have a long term partner who is also the father of my 11-year-old son. I tell him stories about his grandfather and he has long known how he died. He also understands why I have zero tolerance for guns. My brother recently relocated to Switzerland where he works as an architect. Interestingly, as he approached and then surpassed my father’s age, he has become more like him in his mannerisms and interests. We get together as a family once a year and while we do not often talk about my father, he does feel present among us. My son loves hearing stories about the many adventures my father took us on when we were children—and we don’t mind indulging him.

While working on the essay for this project, I opened a box filled with documents I hadn’t looked at in well over 20 years: letters, photographs, newspaper clippings, scientific papers, a death certificate, my grandmother’s suicide note, program notes from the memorial service, my dream diary, the murderer’s statements, Jo Ann Beard’s story “The Fourth State of Matter” from The New Yorker. I’ve long feared this Pandora’s Box with its blunt truths: “Manner of Death: Homicide. Date of Injury: 11/1/1991. Describe How Injury Occurred: Shot with 38 Caliber Revolver. Immediate Cause of Death: Gunshot Wound to Head. Signed by Johnson County Medical Examiner.”

I wasn’t sure if opening the box would unleash things I couldn’t put back in again. And although the notarized Certificate of Death filled me with a renewed feeling of dread, I was surprised by the overall sense of quiet I experienced in revisiting these remnants from what seems like so long ago. The many beautiful condolence letters I wasn’t able to fully appreciate back then have allowed me to buttress the image of my father with memories of others. I am reminded that my father did not believe in heaven or an after-life; instead, he always said we live on in the memory of others. This book project, it seems, seeks to do just that: to recall the lives and make sense of the deaths of those who were abruptly and violently torn from us, in the hopes that each account can transcend the specifics of the individual story and give solace or guidance to others who may have to face the ordeal of a mass shooting, and its lifelong aftermath.

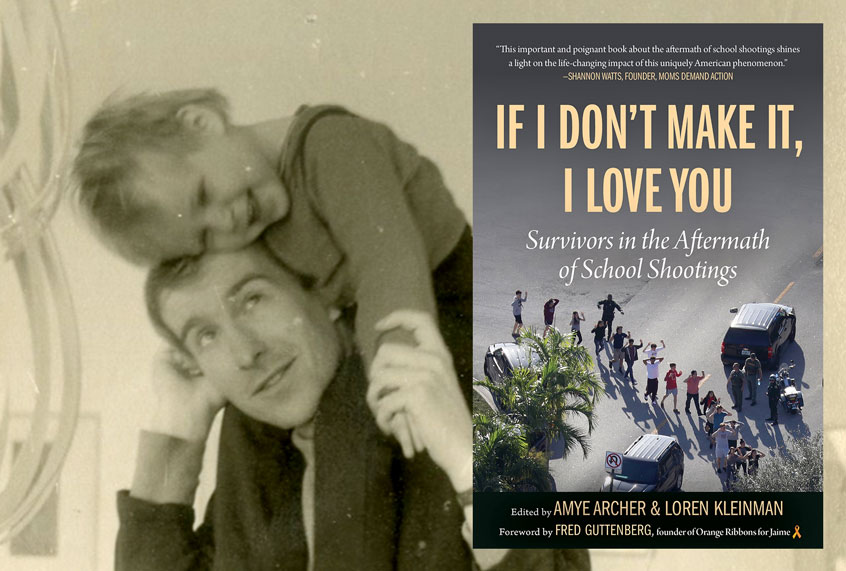

A note from the editors of “If I Don’t Make It, I Love You”:

In the months before the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, we discussed ideas for a new collection. It was clear that gun violence, and those left in its wake, was of particular interest to both of us. For Amye, Sandy Hook changed everything, as it did for many parents across the country. Her twin daughters were the same age as the children murdered on that day, and she has been advocating for change ever since. And for Loren, she’d been writing about trauma for years after her own experience with rape. So, we started our project with what we thought was a simple question: What happened to those who survived Columbine? We wondered how they moved forward and what their lives looked like 20 years later. Then, the Parkland shooting happened, and it became clear the intersectionality between trauma and mass shootings could no longer be ignored. And as we worked on this project, a collection of 84 first-hand accounts from survivors of school shootings, we were reminded of the humanity of those killed and those who survived. How both the dead and the living were part of a life beyond the shooting, and so we committed to the difficult task of assembling their stories, of providing a platform to speak their truths.