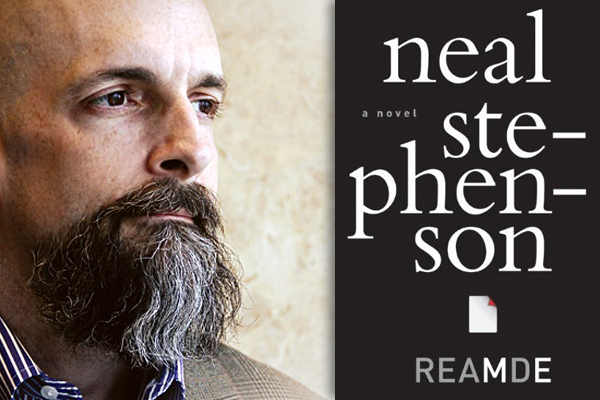

The blurb on the back of my review copy of Neal Stephenson’s new novel, “Reamde,” described it as “his most accessible novel to date.” I frowned when I read those words: Accessible? This was supposed to be a good thing?

In my house, the arrival of a new Neal Stephenson novel every few years (or, in the case of his epic three-volume “The Baroque Cycle” masterpiece, every six months) is always an occasion for great celebration — as well as an associated dramatic collapse in work productivity. That’s been the case ever since I fell in love with “Zodiac: An Eco-Thriller” in 1988 and was enraptured, along with almost every other science-fiction geek, by “Snow Crash” in 1991. A large part of the allure is Stephenson’s uncompromising inaccessibility, his marvelous, sui generis ability to marry complexity, ambition and profound geekiness into a riveting narrative.

Let’s review, briefly, Stephenson’s last three offerings. “Cryptonomicon” wove the entire history of the modern computer, from Alan Turing onwards, into a wild yarn featuring Nazis, gold and Linux geeks. “The Baroque Cycle” trilogy raised the stakes impossibly further: He covered the story of the Enlightenment, including the birth of science and the evolution of money. With pirates and harem girls! Most recently, in “Anathem,” he structured his tale around fundamentally gnarly questions of existential discourse that have been bedeviling the smartest human minds for thousands of years.

Rare indeed is the writer of speculative fiction who can tell a ripping yarn that simultaneously explores the deepest roots of technology and philosophy. That’s what fans like about Neal Stephenson. And that, I have to say, is not what we get from “Reamde.” Ripping yarn? Sure. Massive ambition? Not so much. How the universe works? Zip.

“Reamde” is a thriller whose basic plot is almost embarrassingly simple. Bad guys — Arab terrorists — want to kill a lot of people. Good guys try to stop them. In the end, there is a truly epic gun battle. Along the way, we have stops in China, the Philippines and a fantasy role-playing game universe that is just different enough from World of Warcraft to be mildly interesting.

There is filigree over all of this that only Stephenson could conjure. The intersection of the virtual world (catering to the “all important Chinese teenager market”) with the machinations of al-Qaida is unexpected and innovative, involving a fatal collision between a computer virus and Russian gangsters. Stephenson’s longtime fans will surely be amused by the Apostropocalypse, a diversion into fantasy semiotics that sheds some light on the constructed history of the gaming world created by “Reamde’s” protagonist — and most interesting character — Richard Forthrast. But whereas in past novels the filigree would reflect deeper structures in unusual and provocative ways, in “Reamde” the filigree is just filigree. There’s nothing beneath the baroque surface.

Now, if anyone has the right to take a break from plumbing the Big Questions of What it All Means and to divert himself with a lesser undertaking, it would be Stephenson. Only a churl would begrudge him such a privilege. Putting aside the daunting question of how even a writer of Stephenson’s talents could continue to keep topping himself every time out, there’s no reason why he shouldn’t head in a different direction every now and then. What’s more — I thoroughly enjoyed “Reamde.” I couldn’t put it down — which, for a thriller, has got to be the highest praise. Despite its 1,000-plus pages, “Reamde” moves right along.

Richard Forthrast, a gaming tycoon with a somewhat disreputable past involving marijuana smuggling across the Canada-U.S. border, is one of Stephenson’s more well-drawn creations, a little creaky, a little worn around the edges — the kind of character that “Snow Crash’s” much younger author could never have captured with such telling detail. And Stephenson’s trademark humor, along with his knack for capturing in exquisite detail the niceties of how technology intersects with daily life, is fully present.

Consider the GPS device:

The GPS unit became almost equally obstreperous, though, over Richard’s unauthorized route change, until they finally passed over some invisible cybernetic watershed between two possible ways of getting to their destination, and it changed its fickle little mind and began calmly telling him which way to proceed as if this had been its idea all along.

Anyone who has ever disobeyed the dictates of their GPS unit knows exactly what Stephenson is talking about, but few of us are clever enough to extrapolate that feeling to a vision of the “cybernetic watersheds” that now surround us. There are numerous such insights in “Reamde,” tucked in between the constant attempts of the novel’s characters to kill each other with a wide assortment of lovingly described weaponry. But throughout, one gets the sense that Stephenson is consciously dumbing down his observations to make them comprehensible to the widest common denominator.

Which is interesting, because a younger Stephenson once told me that he had no interest in dumbing himself down.

I had asked him whether he cared that mainstream readers might be taken aback by the inclusion in “Cryptonomicon” of some fairly dense material on cryptographic theory.

“Not really,” he says. “When it comes down to it, the few pages of the book that have equations on them don’t contain a whole lot of plot or character development. So if you skip over that stuff you miss very little.”

Indeed, to refrain from including the hard stuff, says Stephenson, would be tantamount to giving into what he sees as a popular reluctance to face up to the implications of technological progress.

“To me it seems like there is a kind of a strange denial in a lot of our culture, about just how important science and technology have been this century,” says Stephenson. “There’s just an unwillingness to come to grips with it at all. I don’t deprecate people who feel that way, but I do think that at the end of a century like this one it’s not the end of the world if you toss an equation into a work of art.”

There are no equations in “Reamde.” Oh sure, there’s a level of discourse about virtual world economics and computer viruses that you won’t find in 99 percent of the other thrillers lining the bookshelves of your typical airport bookstore. But there is nothing hard, nothing that will trouble your brow as you sit on the beach with your margarita in hand, and massive tome (or Kindle) cradled on your lap.

Maybe that’s a good thing — maybe it will expose Stephenson to a wider audience than ever before, and pay the mortgage and the college tuition and whatever else he might need while he gets to work on his next mind-blowing epic saga. He certainly hasn’t done anything with “Reamde” that will make me any less interested in seeing what he’s got up his sleeve next.

But I still feel a little wistful. In the course of writing this review, I reread my reviews of his previous novels, and I was caught up by a paragraph in my piece on the concluding volume of “The Baroque Cycle”:

Staring at my 11 pounds, 3,775 pages, roughly 2 million words of Stephensonia, I feel the queasiness of a boa constrictor who has rashly swallowed not one, not two, not three, but four water buffalo. This act of digestive hubris has paralyzed me. How is all this to be reduced to manageable size? Where does one begin? Stephenson doesn’t just care about technology and money and excrement — he cares about the intersection of God and science, the emergence of democracy, the rethinking of religion, the birth of the digital computer, and the abolition of slavery. All are mixed in with a love story, an action thriller, the search for Solomon’s gold, an intellectual duel to the death between Gottfried Leibniz and Isaac Newton, and the rise and fall of kings and nations.

Reading that review, I felt a sudden urge to reread all of “The Baroque Cycle,” no matter how intimidating the prospect. But I don’t expect I’ll ever want to reread “Reamde.” “Reamde” is disposable Stephenson. You can take it to the beach, and when you’re done, give it to someone else and not look back.