Where did people get the idea that summer is the time for getaway fiction? When the nights come on fast, dark and wickedly cold, there’s no better time to hole up with a stack of novels, especially when they’re books that promise to carry you off to new worlds populated by intriguing, if not always admirable, people. This winter’s crop of fiction transported us to a whacked-out Arizona suburb, the spirit-haunted world of the Haisla Indians, a stormy Scottish island full of secrets and legends, a Tennessee valley about to be flooded into oblivion and the runaway’s first choice — the bespangled big top itself. So scotch the holiday parties, stash your snow books and join us for a midwinter adventure … without ever leaving your chair.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

The Aerialist

By Richard Schmitt

Overlook Press, 295 pages

Everybody has fantasized about running away to join the circus, but what’s it like to really do it? What happens when the running away is over and the new, three-ring life begins? In Richard Schmitt’s beguiling debut novel, Gary Ruden, a luckless, face-in-the-crowd Floridian, bolts away from his troubles one fateful night and winds up rushing headlong into destiny. Gary, it turns out, isn’t Joe Average after all. He’s a man with a gift.

“The Aerialist,” like its agile protagonist, has a way of pulling off complicated moves with seemingly effortless grace. As we follow Gary on his rise from demoralized cleaner of elephant dung to world-class tightrope walker, we see his vagabond world in all its rough beauty — a place of acrobats and animal trainers, peanut vendors and sequin sewers. Schmitt skillfully juxtaposes Gary’s first-person narrative with vignettes from the lives of other members of the traveling show, and the result is a richly textured tale that knows exactly when and where to shine its spotlight.

Like all worthwhile literature, “The Aerialist” (the latest from Overlook Press’ Sewanee Writers’ Series) is at once refreshingly unique and enjoyably easy to relate to. Gary’s vibrant coterie of strongmen and spangly temptresses is — Hallelujah! — a breed apart from anything else in fiction this season. Schmitt, who thanks one of the Flying Wallendas in his acknowledgments, masterfully escorts us through a world few of us have ever truly seen — the colorful slang, the backstage pecking order, the addictive joy of rolling from town to town. He gets beyond the reader’s romantic big-top notions and straight into the heart, sweat and soul behind the nightly magic, makes us understand the weariness of a midget who complains that people “say they’ve been to the circus once, like there’s only one.”

Yet for all this novel’s exotic flair, it remains essentially a simple story of what happens when we dare to tap into the extraordinary in ourselves. When Gary’s just a regular guy, he’s barely even a member of society. Ironically, it’s only when he hooks up with his oddball troupe and unleashes his talent for defying solid ground that he finds his place in the world. Most of us don’t need to hitch ourselves to an elephant’s tail to find out who we truly are, but Gary’s path to discovery will be familiar to anyone who’s ever struggled to fit in. And how lovely for us as readers to meet a character who finds a place in the world while striding so confidently above it.

— Mary Elizabeth Williams

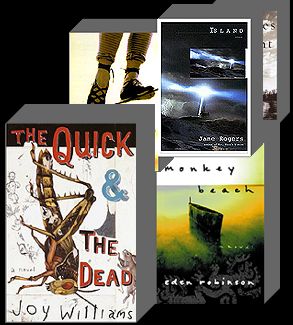

Island

By Jane Rogers

Overlook Press, 261 pages

Nikki Black, the narrator of this trim rural Gothic, may be angry, deceitful, cynical and sexually manipulative, but at least she has a purpose. She arrives on the island of Aysaar, in the Hebrides off the coast of Scotland, intent on killing her mother. Abandoned on the steps of a London post office as an infant, Nikki has been raised “in care,” an experience she says has made her “like the boy in ‘The Snow Queen.’ He gets a splinter of ice in his eye. It changes everything he sees to cold and ugly.” Raging against the grim institutions and “tragedy-junkie” foster parents who have taken turns raising her, and fighting a propensity to paralyzing anxiety attacks, she decides to avenge herself against the author of her misery and loneliness, the woman she says “made me this; the one you can walk away from.”

On Aysaar, posing as a grad student doing demographic research and renting a room from her designated victim, Nikki discovers that she has a “simple” brother, Calum, saturated in the folklore of the wild, primitive island. As Nikki contemplates various plots, a peculiar friendship blossoms between the two and the stormy atmosphere of the island grows ever thicker with paranoia, secrets and incipient violence. The book feels distilled, like north country moonshine, and flavored with peat. There’s something bracing about the purity and focus of Nikki’s hatred. Calum’s tales of “blue men” (the tall, deadly waves in the surrounding sea), a girl raised by seals, a bull that turns into a rock and a mother who poisons her children with salt weave through Nikki’s increasingly deluded matricidal imaginings, giving the goings-on a primal, mythic quality. Rogers (author of last year’s “Mr. Wroe’s Virgins”) works a couple of twists into the path as the confrontation between Nikki’s bitterness and what’s left of her humanity nears, but the pleasure is all in the journey, and the dark, briny, elemental world she creates. You can almost taste the salt on your lips.

— Laura Miller

Monkey Beach

By Eden Robinson

Houghton Mifflin, 374 pages

Eden Robinson’s first novel, “Monkey Beach,” is also the first full-length work of fiction by a Haisla writer. Haisla are Indians, or First Nations people, living in British Columbia, Canada. Robinson, acknowledging that the Haisla might be unfamiliar, formally introduces her readers to this foreign, icy world: “Find a map of British Columbia. Point to the middle of the coast. Beneath Alaska, find the Queen Charlotte Islands. Drag your finger across the map.” It’s almost as if she’s saying, “We are a people you don’t know about. This is where we live. Welcome.”

Robinson uses the same austere style to archive the chambers, valves and muscles of a heart and to describe, step by step, how to contact the dead. But her writing can also be magical; the words swirl together as they comb the vast, wild geography of her homeland and the dark, mystical spirits of her culture. Other times, especially in her dialogue, her voice is deadpan and shocking — a punch-in-the-stomach kind of humor that compels you to cough up a laugh. This calculated variety makes “Monkey Beach” lively and surprising, and ultimately addictive. Robinson jumps back and forth in time and from dreams to reality so frequently that it’s easy to feel dazed. But her task is considerable. From this massive collision between an ancient culture and the Western world, the author manages to wrench forth the story of a family and a culture besieged by tragedy.

“Monkey Beach” is also Lisamarie Hill’s coming-of-age story. She goes through the universal stuff — period getting and boy liking — but Lisa also bears her family’s past like an oversize cloak draped over her fragile shoulders. Her Uncle Mick is a reckless, defiant Native-rights activist who listens to songs like “Fuck the Oppressors” and worships Elvis Presley. Aunt Trudy is an incorrigible drunk, but she’s also perceptive and honest, hard-edged like her daughter Tab. Ma-ma-oo, Lisa’s grandmother, holds fast to tradition, yet gleefully watches “Dynasty,” shouting at Alexis Carrington, “He’ll never make you happy!”

Lisa’s “perfect” brother, Jimmy, is determined to leave their Kitamaat reservation and become an Olympic swim champion. At the beginning of the book, Jimmy has been lost at sea and Lisa’s parents have left to monitor the search party. Memories flip through her mind as she sits smoking nervously, and bit by bit Robinson unravels the first 20 years of Lisa’s life. As resilient as Lisa and her family and friends seem to be, something nips at their collective heels and threatens to bring them down. Penetrating this very modern reality of alcohol, drugs, depression, oppression and fatal accidents are the spirits of the Haisla ancestors, who sometimes, but not always, buoy up their kin. Anyone trying to contact them should, Robinson instructs, “examine your willingness to speak with them. Any fear, doubt or disbelief will hinder your efforts.” Robinson’s ambitious novel, on the other hand, embraces the dead with gusto. She lets them roam free and pass judgment on the modern world that has followed them.

— Suzy Hansen

The Quick and the Dead

By Joy Williams

Knopf, 308 pages

This is a book whose characters, mostly pubescent girls, are as prickly and uncongenial as the cactuses in its Southwest desert setting. Alice, who lives with her TV-news-obsessed grandparents, is a misanthrope with an “unevolved sense of compassion,” prone to surly minisermons about humanity’s crimes against nature. When Annabel, whose father is wrapped up in fending off nightly visitations from his wife’s ghost, tries to tell Alice how her mother was struck by a car after leaving a fish restaurant, Alice’s response is, “I would absolutely refuse to go into any fish restaurant. Entire species of fish are being vacuumed out of the seas by the greed of commercial fishermen.” The third girl in this trio of friends, Corvus, drifts and dreams through a life made meaningless by the death of her parents.

Though the premise of “The Quick and the Dead” has to do with how people respond to irredeemable loss, plausible psychology takes a back seat to spectacular eccentricity in Williams’ novel. The real attraction is her characters’ conversations — peculiar, ingenious and entertaining in a way that’s extravagantly fictional. By the time we meet the formidable Emily Pickless, an 8-year-old prodigy who rubs dirt into her hair and understands that “you only had to know one person in your life, and that was yourself,” all disbelief has been suspended, so that when Emily is virtually adopted by a middle-aged millionaire and big-game hunter who’s convinced she’s an “unreaped whirlwind,” a “Dalai Lama … but not in the airy-fairy sense,” it seems perfectly reasonable.

There isn’t much of a conventional story to this novel, though plenty happens, including several unpleasant deaths and many more unpleasant thoughts. A man Emily’s mother contemplates marrying tells the girl that he dislikes dogs because dogs scavenged the body of Christ right off the cross:

“I’m telling you something historically accurate. Dogs have been getting away with too much for too long.”

“Have you ever bitten anyone?” Emily asked. “I wish I could bite someone whenever I felt like it.”

“You look like a biter,” J.C. said. “You feel like biting me?”

But Emily demurred.

“Come on, come on.” The arm J.C. extended had black hairs growing on it up to the elbow, where they abruptly stopped. “Not everyone would allow you this opportunity.”

These people are capable of anything, and not every author would allow so many of them to run around loose in her novel — that is, if there’s any other author who could invent such a crew. “The Quick and the Dead” isn’t for readers who like their books solidly grounded, but for those seek genius in its most idiosyncratic form: Sink your teeth in.

— Laura Miller

Provinces of Night

By William Gay

Doubleday, 274 pages

“Provinces of Night” begins with a mysterious mason jar dug up from a hill in Tennessee. William Gay’s second novel announces its ambition right away with this nod toward a poem by Wallace Stevens, and a homage to William Faulkner plays out through the rest of the book. Conjuring these two literary ancestors seems appropriate: Gay has both an exquisitely tuned ear and a finely balanced feeling for the mythic resonances to be found in Southern life.

Yet “Provinces of Night” proceeds on its own deliberate, dignified path, gradually introducing three generations of the fractured, quick-tempered Bloodworth clan of Ackerman’s Field, Tenn. It’s the early 1950s, just before the Tennessee Valley Authority is set to flood the area they’ve lived in for years to bring electricity to the surrounding countryside. After 20 years spent roaming for reasons even he is not entirely clear on, E.F., the Bloodworth patriarch, makes his way back to his wife, who’s lost all interest in his whereabouts. His three sons are living out versions of his disconnected life: Boyd leaves his own son to go north and track down the wife who’s left him for a peddler; Warren is a good-time Charlie who spends his time boozing and pissing off his wife; and Brady is an odd bird who still lives with his mother and practices his own brand of black magic on his enemies.

Boyd’s sensitive, introverted teenage son, Fleming, is the emotional center of the novel. Left to fend for himself when his parents disappear, he discovers his own way out of the mistakes that have ensnared his relatives. That Fleming is an aspiring writer who scrounges for whatever books and magazines he can get his hands on is perhaps a predictable touch, but his coming-of-age, coming-into-knowledge story still gives just the right dose of structure, and a ray of hope, to the novel. Living alone in a secluded cabin out of sight of the nearest neighbor, virtually devoid of adult guidance, Fleming lives a sort of Tom Sawyer fantasy — he has the luxury and the misfortune of solitude interrupted only when he chooses.

Gay mixes Southern humor and Southern portentousness with an assured hand. You can’t help chuckling as E.F. saves bus fare by tricking a pompous, stupid cattle dealer into driving him 400 miles by pretending to have cattle to sell (he claims he has huge doctor bills after his son was gored by a bull after he went “plumb off the deep end. He’d started tryin to keep my cattle from breedin. Called it fornicatin. He couldn’t stop it so he started marryin em … They kept commitin what he called adultery with cows they wasn’t married to.”) But even more often, you’re blown away by gorgeous sentences like this one: “It was raining, a slow dawn drizzle from an invisible sky, fog rolling up out of the hollow so blue and dense the dripping cedars looked spectral and insubstantial, the oaks and hickories penitent and without detail, just dark slashes of trunks rearing up out of the mist.”

— Maria Russo