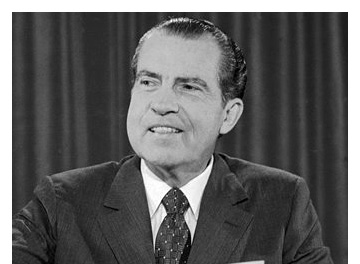

Like some third-world conflict that flares up just when you thought everything was settled, Richard Nixon is back again. Played by Frank Langella in a Tony Award-winning performance (opposite Michael Sheehan’s David Frost) in Peter Morgan’s “Frost/Nixon,” he’s the toast of Broadway. And just in time to commemorate the 35th anniversary of the Watergate break-in, bookshelves are inundated with Nixon lit.

For the uninitiated, Elizabeth Drew’s “Richard M. Nixon” provides the only outline of his life and career currently in print. The book doesn’t have much else to recommend it; at just 147 pages, it seems rushed, as if it was phoned in or culled from old essays. Drew doesn’t much like Nixon, which puts her in step with most journalists who knew him, but unfortunately she also seems uninterested in him. Having established that Nixon was a “pragmatist” — Drew seems to spit the word out, as if it were unclean — and that he had “no guiding philosophy,” she settles down to systematically write off every achievement of Nixon’s administration, ascribing them to luck, clever aides and a Democratic Congress (Nixon apparently being the only president who ever had all three).

Much more fun is James Reston Jr.’s “The Conviction of Richard Nixon: The Untold Stories of the Frost/Nixon Interviews,” which plunges us right into the unholy mind of the most disgraced president — though, to be fair, we should say the most disgraced president yet — in U.S. history. Reston was already a veteran researcher of two Nixon books before being asked by David Frost, the popular English TV interviewer, to build a research team for the 1977 televised interviews (on which the Broadway play is based). “This bout of heavyweights,” writes Reston, “remains the most watched public affairs program in the history of television,” with more than 48 million Americans tuning in for “the only trial over Watergate that Nixon would ever endure.”

In a portion of the White House transcripts reprinted in Reston’s “The Conviction of Richard Nixon,” the beleaguered president cries out rhetorically to his flunky, Charles Colson: “Here we’ve done great things. We’ve got greater things to do, and they’re talking about this goddamned Watergate.” The remark seems almost prescient, as if Nixon somehow knew that everything he had ever done would heretofore be pushed into the background by the impending scandal. It almost sounds like a plea to the next generation of historians to remember him for something besides Watergate.

As if in reply, three other recent books on Nixon argue that other aspects of his career, both good and bad, are worth remembering. Jules Witcover’s “Very Strange Bedfellows: The Short and Unhappy Marriage of Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew” plugs a gap in our understanding of one of the minor mysteries of post-World War II presidential politics: namely why Nixon would have chosen a nonentity like Spiro Agnew for his vice presidency in 1968. Agnew, more right wing than Nixon himself, was an ideological attack dog who could do much of the public barking that Nixon himself no longer had the time and inclination for — in the witty words of the late senator from Minnesota, Eugene McCarthy, referring to Nixon’s role as Dwight Eisenhower’s redbaiting V.P., Agnew became “Nixon’s Nixon.” As it turned out, Nixon didn’t like his Nixon any more than Eisenhower had liked his, and, in Witcover’s judgment, “was guilty not only of this original choice of Agnew but also in then denying him as vice president entry into the inner circle” — exactly the way Ike had treated Nixon.

However obnoxious Agnew was and however revealing of Nixon’s character his treatment of his vice president may be, Spiro was small potatoes in Nixon’s presidency. Robert Dallek’s “Nixon and Kissinger: Partners in Power” is the best book yet on what the author terms, without hyperbole, “one of or possibly the most significant White House collaboration in U.S. history.” Nixon, as bigoted a man as any who ever occupied the White House, didn’t like his Jewish secretary of state any more than he did Agnew, but thanks, perhaps, to the pragmatism Elizabeth Drew sniffs at, Nixon understood, as presidents before and after him have not, the importance of having a man who was smarter than he for an advisor. Nixon’s and Henry Kissinger’s spectacular successes with China and in thawing the Cold War provide “some constructive lessons for the present and the future on the making of foreign policy.” Their notable failures in expanding and prolonging the war in Southeast Asia and their blind eye to the growing problems in Central Asia also stand “as a cautionary tale that the country forgets at its peril.”

Margaret MacMillan has picked the juiciest Nixon subject of all in “Nixon and Mao: The Week That Changed the World.” She details Nixon’s 1972 trip to China and meeting with Mao Tse-tung, which, at 98 percent, registered the highest public awareness of any event in the history of Gallup polls. The story of the most important political meeting since World War II makes for fascinating reading, particularly in light of China’s emergence as a 21st century economic superpower. MacMillan puts Nixon’s political shrewdness in bas-relief, contrasting it to ideology of his contemporary conservative critics. Pat Buchanan was so furious over what he perceived as the selling out of Taiwan that he threatened to resign from the White House staff (he didn’t). William F. Buckley Jr., who went along on the trip, condemned Nixon and went on to throw his support to an obscure Ohio congressman named John Ashbrook, who was trying to block Nixon’s reelection.

Neither Buchanan nor Buckley — nor, for that matter, few other Americans of the right or left besides Kissinger — understood as Nixon did that the first steps toward ending the Cold War had been taken. The American right, had it been completely honest, would have awarded him at least half the credit for bringing down the evil empire that they today give to Ronald Reagan.

For millions of Americans my age who graduated from college in the 1970s, the single most important political truth is that my generation got more of what it wanted from Richard Nixon than from any president from FDR to W. — more than we got from JFK and almost certainly more than we would have gotten from him had he lived.

Let’s start with integration, because that’s what Nixon did. When Nixon took office in 1969, fewer than 6 percent of black children were in desegregated schools; by the time he resigned, more than 90 percent of black children in the Southern states were enrolled in integrated school systems. Nixon courted Jackie Robinson, trying to establish a black presence in the Republican Party, and was the only American president to invite Louis Armstrong, perhaps the most important American cultural figure of the 20th century, to the White House.

Because he wasn’t a crusader and seldom addressed racial matters, because he openly courted and pandered to white Southerners in the 1968 election — and because, let’s face it, he always reminded us a bit of the stuffy but amiable, semibigoted uncle who preached to us about the virtues of self-reliance and the American dream — we never really gave Nixon his due for his achievements in desegregation. One of his most liberal critics, Tom Wicker, did. In his massive 1991 study of Nixon, “One of Us,” Wicker came to the conclusion that “the Nixon administration accomplished more in 1970 to desegregate Southern school systems than had been done in the sixteen previous years or probably since.” As if to anticipate those who would later put this success to a Democratic Congress, he added, “There’s no doubt either that it was Richard Nixon personally who conceived, orchestrated and led the administration’s desegregation effort … [which] resulted in probably the outstanding achievement of his administration.”

On the environment, Nixon was no Teddy Roosevelt or even FDR; he was simply better than most presidents, and, like most presidents when choosing between “smoke and jobs,” chose jobs. Environmental issues were one area that benefited greatly from Nixon’s famed indifference to domestic affairs. (He was fond of saying that Congress could take care of matters at home, but “you need a president for foreign policy.”) John Erlichman was the White House aide most concerned with conservation, and, happily, many times he was able to push something in front of Nixon’s face and get him to sign it. According to Wicker, Nixon’s attitude toward the environment could be summed up in a single phrase: “When in doubt, make it a park.”

His record on Indian affairs has remained practically invisible to this day, but less than two years into the second Nixon administration, the executive director of the National Congress of American Indians, Bruce Willkie, boldly stated that Nixon was “the first U.S. president since George Washington to pledge that the government will honor obligations to the Indian tribes.” Peter MacDonald, a Navajo leader, called Nixon the “Abraham Lincoln of the American people.” Do we disregard that remark because MacDonald was a Republican?

And while we celebrate the 35th anniversary of Watergate, let’s remember to raise a glass on June 23, the 35th anniversary of the enactment of Title IX, which did more for girls’ and women’s sports in this country than all legislation by all other American presidents combined.

In retrospect, how exactly do we classify Nixon? When I was a college student, it was easy: He was a conservative. We never thought to define the term in a way that might connect it to the tradition of someone like G.K. Chesterton, and it would have been unthinkable to associate Nixon’s politics with the progressive strain in the Republican Party — think Lincoln and Teddy Roosevelt — that resurfaces every 40 years or so.

To many of us back then, a conservative was simply someone who was anti-communist, who resisted the civil rights movement and supported the war in Vietnam. It wasn’t clear to us at the time that by two of those three standards a great many Democrats qualified as conservatives, especially the two Democratic presidents, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, who got us into Vietnam in the first place. Nixon was the one who got us out of Vietnam, but — and there always seems to be a “but” when discussing any of Nixon’s accomplishments — he also ordered the dropping of more bombs than any president in our history.

One thing can be said with certainty: He was no doctrinaire conservative when it came to economics. He never worshiped the idol of the balanced budget and didn’t hesitate, when he truly thought it was needed, to use the power of the federal government to stimulate the economy. In her 1991 study, “Nixon Reconsidered,” Joan Hoff concluded, “By and large, politics made Nixon more liberal than conservative in economic matters, confounding both his friends and enemies, as he also did on issues of domestic reform, especially civil rights and welfare.” But “as a Republican, he was willing to move beyond the boundaries of the New Deal and Great Society, both set by Democratic presidents.”

Garry Wills was willing to go one step further. In his pre-Watergate analysis of Nixon, “Nixon Agonistes,” Wills called Nixon “a classical liberal,” a president who didn’t turn away from what he saw as the federal government’s obligation to maintain well-being. (Nixon, for all his expressed indifference to everything besides foreign policy, also declared, “I was determined to be an activist President in domestic affairs.” Did he contradict himself? Very well, then he contradicted himself.)

Why is it that many of us have been so reluctant to give Nixon any credit for policies that by the standards of most administrations would be considered liberal or at least progressive? Probably because our definition of liberal has little to do with politics and economics and has more to do with what we regard as being a good person. By that definition, Richard Nixon does not qualify. He was petty, vindictive, paranoid and resentful of those who, like Kennedy, he felt were born into privilege. How in the world did he ever manage to get so much done? Kissinger’s remark can practically stand as his epitaph: “Can you imagine what this man would have been if someone loved him?”

For a man derided by so many of our intellectuals, Nixon loomed large in 20th century history and culture. With the exception of Lincoln, Nixon has probably been portrayed by more great actors than any other chief executive. In addition to Frank Langella in “Frost/Nixon,” he has been played by Rip Torn (in a 1979 CBS miniseries from a book by former Nixon staff member John Dean and Taylor Branch), Jason Robards Jr. (in the 1992 TV movie “Washington Behind Closed Doors”) and Anthony Hopkins (in Oliver Stone’s 1995 biopic “Nixon”). Robert Altman gave Nixon his own one-character movie, 1994’s “Secret Honor,” with Philip Baker Hall delivering a stream-of-consciousness printout of the post-Watergate Nixon mind. There is even John C. Adams’ 1987 opera “Nixon in China,” with James Maddalena as the heroic president who defied his own party to open up Red China. (Two questions: Has any other American president ever been the subject of an opera? Did Richard Nixon ever attend an opera?)

Of course, what fictional Nixon could adequately contain the same qualities of fake humility, forced pomposity and desperate longing for approval as the real thing? For some purists, only underground filmmaker Emile de Antonio’s 1971 comedy, “Milhous: A White Comedy,” will do. Many of Nixon’s biggest hits, including his “You won’t have Nixon to kick around anymore” speech (after losing the 1962 California gubernatorial race to Pat Brown), are collected in one exquisite movie.

If Nixon was, after all, so dull, why did he light the imaginations of so many serious writers? Peter Morgan, Gore Vidal (“An Evening With Richard Nixon”), Philip Roth (“Our Gang”) and Norman Mailer (“Miami and the Siege of Chicago”) have all taken their shots at him. Mailer, not entirely unsympathetic, nailed him, at least momentarily, at the 1968 Republican Convention: “His modesty was a product of a man, who, at worst, had grown from a bad actor to a surpassingly good actor, or from an unpleasant self-made man — outrageously rewarded with luck — to a man who had risen and fallen and been able to rise again, and so conceivably had learned something about patience and the compassion of others.”

Even Mailer, though, couldn’t sustain an accurate bead on Nixon. As he proved in his memoirs, “RN,” Nixon was no better at figuring himself out than any of his many biographers — which is why the books about what he did are better than the books about who he was. The library of books about and by Nixon (he wrote 11) offer the reader more than enough puzzle pieces to fill in the frame; the problem is that even after filling in all the spaces the picture in the puzzle is a perfect blank. In Garry Wills’ famous phrase, “He lacked the stamp of place” that enables Americans to empathize with their president. There is simply no inkling as to what made Nixon tick, what motivated him beyond personal ambition — and mere ambition doesn’t begin to explain why he could be, when inspired, so spectacularly effective.

In the end, though, it isn’t what a president was like that matters but what he did. In Nixon’s case, just about everything that could be put on the plus side of the ledger has been, if not forgotten, at least obscured by time. Loathed by the left and having left no estate the neocon ideologues wish to claim, Nixon’s stock sells cheap and still finds no takers. On Feb. 26, U.S. News & World Report’s cover story was “America’s Worst Presidents,” which featured a photograph of Nixon, along with photos of Herbert Hoover, Ulysses S. Grant and John Tyler. In the actual feature, Nixon is only ranked ninth worst, tied with Hoover, but a magazine cover with, say, James Buchanan (first), Franklin Pierce (fourth) and Millard Fillmore (seventh) just wouldn’t sell. Last December, when Nixon’s second veep and successor, Gerald Ford, died, the nation, or at least the news media, went into an absurd paroxysm of grief for a man who was surely the most insignificant president to occupy the White House since Warren Harding. (Is Ford the only president whose accomplishments were outstripped by his wife’s?)

Has Nixon left us any political legacy? His detractors would point, and rightfully so, to his startlingly candid pronouncement, “If the president does it, it isn’t illegal.” Such an idea is dangerous enough in the head of a pragmatist; in the mind of an ideologue, it’s positively scary. But surely there is more than that to be learned from the career of the only other president besides FDR to have won on four out of five national tickets. (The only one he lost, to Kennedy in 1960, was by a handful of dubious votes.) He proved, at his best, the adage that politics is the art of the doable, and that pragmatism, as numerous American philosophers including William James could remind us, is not in and of itself cynical or unprincipled.

Nixon’s life and work were much more than Watergate. But even if that scandal were to be the only thing that kept us talking about him, I’ll bet the old sonuvabitch would grab the deal.