In the autumn of 1919, shortly after the end of the First World War, a strange book began circulating in Western Europe and North America. “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion” consisted of an 80-page manifesto outlining, in detail, how the existing powers in the world — churches, governments and the like — could be toppled using class hatred, war and Bolshevism, thus establishing a world empire ruled by Jews. Supposedly created by a cabal of nefarious Jews during an 1897 meeting, “The Protocols” was, of course, an anti-Semitic hoax, but that didn’t stop it from becoming a sensation in Europe — and one of the first major conspiracy theories of the 20th century.

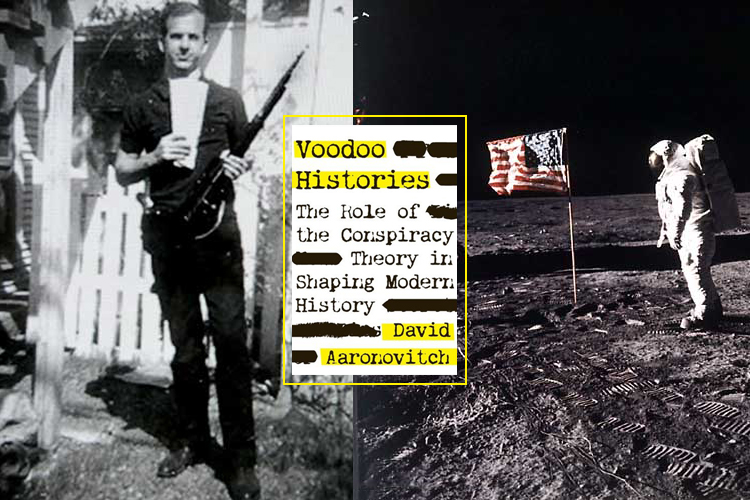

As British journalist and Times of London columnist David Aaronovitch explains in his new book, “Voodoo Histories: The Role of the Conspiracy Theory in Shaping Modern History,” it was far from the last. “The Protocols” was the first in a line of outlandish theories that have gained popularity over the past century. From faked moon landings to Holy Grail coverups and missing Hawaii birth certificates, a great many people have been willing to believe some very farfetched ideas. In this fascinating and thoroughly researched book, Aaronovitch dissects not only how many of these theories were invented, but also how they prey on our personal fears and, in some cases, metastasize into our popular culture.

Salon spoke to Aaronovitch by phone about the Internet’s role in spreading conspiracy theories, our new golden age of paranoia, and the dangers of believing Naomi Klein.

What prompted the book?

There is a specific moment I mention in the book, when a very intelligent man turned to me during this long car journey and with a kind of mischievous pleasure tried to convince me that the moon landings never happened. I listened to him about the photographic reasons why so-and-so shot was impossible and something else couldn’t happen — I found myself wondering what the attraction of this was for him. To fake something like the moon landing would be incredibly difficult if not completely impossible. Why do clever people believe dumb things?

People put an enormous amount of resources and commitment into these stories, and large numbers of people believe them. A Venezuelan professor recently claimed that the United States caused the Haiti earthquake with an underground nuclear test. What kind of background evidence is there for that? None. But these kinds of stories are ubiquitous.

In recent years, people like the birthers and the 9/11 truthers have gotten a lot of press coverage and pop-cultural play. Are we in a new golden age of conspiracy theories?

I think we live in a more conspiracist period. There’s no question there are more of them, and they’re more global, and they take off more quickly. They’re also more complex and relate to virtual communities rather than real ones. I think it’s because of global interdependence. We live a global period, and there’s a huge temptation among people to believe there is a master plan, because otherwise the suggestion is we’re interdependent and the world is chaotic — and that’s a mindfuck.

There are entire societies where the default position is to believe in conspiracy theories, like in Pakistan or Iran. There are very few people in the Pakistan military, for example, who don’t believe that Bush was behind 9/11. But they’re also probably more easily dispelled, especially in places like the U.S. or Britain. Maybe I’m a false optimist, but I think we have a good skeptics’ movement. My book has done quite well in the U.K. I do think there is some appetite amongst the skeptics that we’ve had enough of this shit and it’s time to fight back.

If they’re so ubiquitous, why do some conspiracy theories become hugely popular while others don’t?

They tend to be mimetic and fit into preexisting or fashionable patterns of belief. In the ’80s there’s a very particular type of conspiracy theory about nuclear companies and the American and British governments. Many people believed that this old British lady [who was involved in anti-nuclear activism] was bumped off by the Secret Service. It suddenly appeared during the stand-off between the Soviet Union and Reagan at the end of détente, and suddenly disappeared after the beginning of the Gorbachev-Reagan agreements [or Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty].

A popular conspiracy theory has to be a story that fits into what people are thinking about, and it should succeed as a story with a narrative structure. The moon-landing conspiracy theory, for example, became popular after a successful movie came out with the exact same premise, but set on Mars.

What makes us susceptible to conspiracy theories?

We want to believe theories that contradict the idea that young, iconic people died senselessly. If a story takes away the accidental from their death, it gives them agency. After the JFK assassination, it was unbearable to many people that they could live in a country where a lone gunman could kill a president. In those circumstances, it’s not surprising that an overarching conspiracy theory emerges. It suggests that somebody is in control, rather than that we’re at the mercy of our neighbors and to some extent of ourselves (as was the case with Marilyn Monroe and Princess Diana). It’s the urge to make sense of a particularly traumatic moment.

In some ways, it’s not that different from the impulse to believe in God.

It is deep down a leap of faith, but it doesn’t present itself as a leap of faith. It presents itself as not only rational but a better kind of rationality. It’s incredibly important that a conspiracy theory has the appearance of science. The literature on Kennedy is beyond voluminous. It’s absolutely enormous. There are vast tomes to suggest that the CIA did it, or other people did. [Conspiracy theorist] David Ray Griffin has come out with a half dozen 9/11 books, and all of them have hundreds of footnotes. They’re either to instant news reports that have since been contradicted, or to other conspiracy theories — but the work nevertheless takes on the appearance of scholarliness.

On the Internet, it can often be very difficult to tell what’s true and what’s not. Do you think the Web is helping these conspiracy theories become more popular?

The Internet is a gigantic version of what they faced in the 1920s, when the first widely distributed pamphlets about “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion” came out. They were cheap and easily available. It was an age of increasing literacy. It prefigured what we have on a much bigger scale now. It was hard in these circumstances to distinguish the authoritative from the quack. It’s like medicine in the Wild West: There are some doctors around, but there are a lot of people on strange wagons saying they can cure your blindness.

We always had this problem to a degree, but what the Internet has done is revolutionized the amount of information. We know that Google operates on an algorithm that tells you what’s popular, but it seems to be telling you what’s authoritative.

I also think the Internet also allows for a segregation and reinforcement of certain ideologies. Liberals can only read liberal sites, if they want to, and conservatives will only read conservative sites.

I think it’s really true. It’s interesting to me how the Clinton conspiracy [claiming that the Clintons were involved in the death of deputy White House counsel Vince Foster] really first took off on the Internet — when the Internet was just really getting started. It blindsided a lot of journalists as to where this stuff was coming from. And now it’s just so quick. Before you know where you are, there are a dozen stories saying something — and they’re circular.

You deride Naomi Klein’s “No War” in the book. Do you think Klein is a conspiracy theorist?

Her last book, “The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism,” was essentially a gigantic conspiracy theory book — claiming that chaos is more or less created in order to encourage capitalism. It was a fashionable book, and I think people wanted to buy it because they felt guilty. It was bought by guilty capitalists. It’s not like “The Shock Doctrine” was being sold out of baskets hand-woven by hippies.

Naomi Klein was in Iraq at the same time as me and had this theory that the U.S. was behind an attempt to destroy the Iraqi intelligentsia, to run Iraq like America. It was a crazy theory she convinced herself of. At that point what the Americans wanted was a strong Iraqi presence for them to hand the country over to. She’s not first and foremost a conspiracy theorist, but she is in passing.

What, in your opinion, is the most implausible conspiracy theory to gain wide acceptance?

I think 9/11 is the most baroque. I can’t tell you what it feels like to see videos on YouTube of David Ray Griffin addressing people about it — one of America’s leading theologians expressing with absolute certainty the existence of a conspiracy so ludicrous it takes your breath away.

I do think it’s pretty wonderful that people think the Catholic Church covered up the bloodlines of Christ. “The Da Vinci Code” was marketed as the greatest conspiracy in history, but it’s amazing how few people thought through the fact that if Jesus had had a child who’d come to the south of France in 35 A.D., the number of descendants of Christ would be in the tens of millions.

Why does it matter that these people are wrong? Shouldn’t they be allowed to believe what they want?

I do think it actually matters what is true. The search for the truth is an important search, and if it isn’t, we’re lost in all kinds of ways. We’re lost in the fields of Holocaust denial. We’re lost in being able to compare what is good and what is bad because we can’t agree what actually happened. We’re lost when it comes to guarding minorities against populist agitation. Nobody’s going to die from saying Shakespeare wasn’t Shakespeare, but in other areas, when the truth suffers, our decision making suffers. When there is no authority to the truth, prejudices thrive.