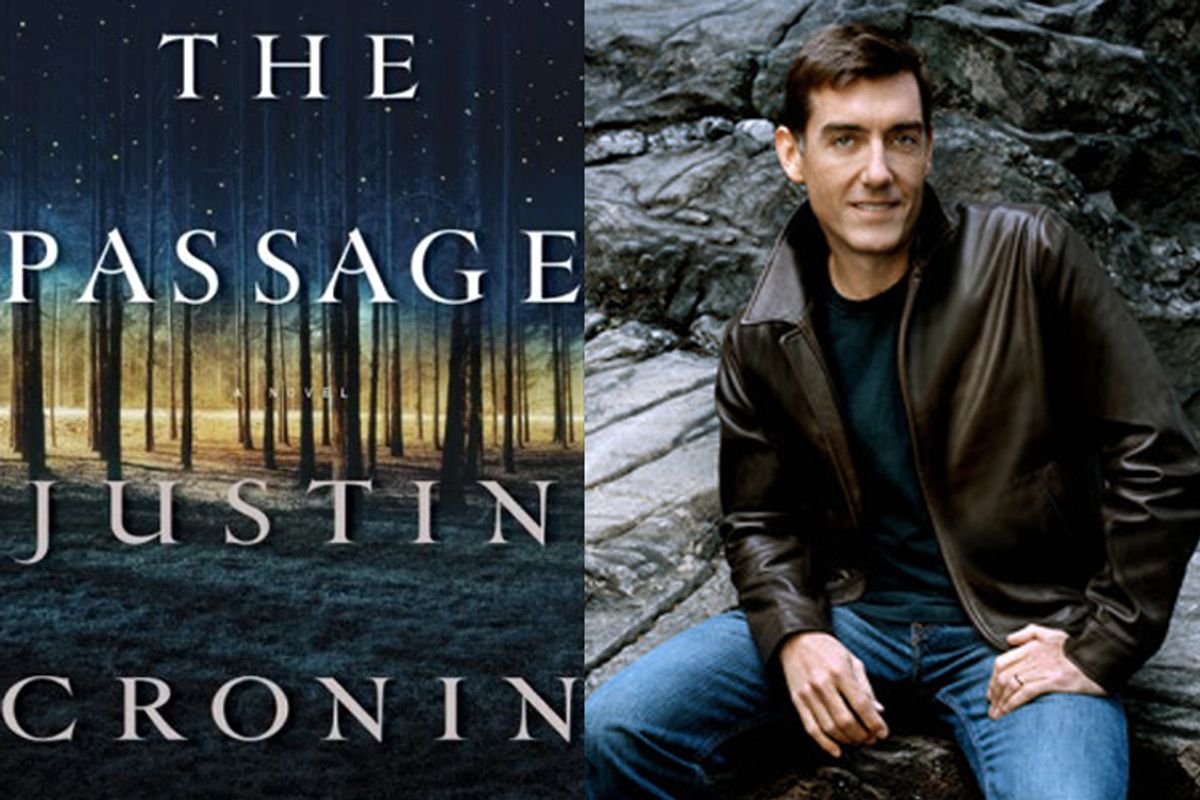

As most Salon readers are already aware, we really love Justin Cronin's "The Passage." That's why we selected Cronin's epic book, about vampires and a post-apocalyptic America, as the subject of the first-ever Salon Reading Club. Over the past month, Laura Miller and Salon readers have been discussing everything from the book's take on mortality to its similarities to Cormac McCarthy's "The Road." (Check out more of the Salon Reading Club here.)

Over the course of the past month, we've also been collecting your questions for Cronin -- about, among other things, his fascination with the end of the world, President Obama and the meaning of the word "wicking." Here are his answers.

As I'm sure you know, you're certainly not alone in setting a novel in a period after a great die-off of human life. What do you think is the American novelist's fascination with the apocalypse at this particular historical moment?

I think stories of this kind grow out of uncertainty, and these are very uncertain times, to say the least. I grew up during the Cold War, when everything seemed very tenuous. For many years, right up until the fall of the Berlin Wall, I had vivid nightmares of nuclear apocalypse. But the good thing about the Cold War -- and it was the only good thing -- was that we knew what to be frightened of. There was one danger so overwhelming that it pretty much pushed all other worries off the table.

I think we’re even more anxious now because we don’t know exactly what to be afraid of. The collective national trauma of 9/11 was profound, not least of all because its images made no sense. Planes flying into buildings: Who ever expected such a thing? The character Richards is the voice of this state of mind -- he pretty much articulates it chapter and verse. The things we fear now have a shadowy quality, moving at the edge of our vision -- like the virals, who "move at night, in the trees."

About landscape, which itself seems to become a character in the second part: What is it about the West -- especially the desert West -- that invites so many writers to make it the setting for the post-apocalypse?

In part this solves a practical problem. In a dry climate, the ruins of the old world would be better preserved and hence provide a more vivid and detailed backdrop. Houston, where I live, would turn to gelatin in just a couple of decades. Las Vegas, on the other hand, would stand intact, like the pyramids. There’s also something about the West that invites epic storytelling. One of the great themes in American literature is the individual’s confrontation with the vast open spaces of the continent. In this sense, "The Passage" is also a western.

I'm curious which parts of the book grew out of your daughter's contribution. I'm also curious, of course, if she's read it. She's 13 now, from what I understand, so she'd be old enough.

My daughter and I worked up a basic outline for the whole story. A few specific items were her own creation. For instance, the character Michael was pretty much someone she demanded. (She’s always preferred brainy boys.) The Sunspot was also hers. She wanted one character to have red hair (Alicia). She also named a lot of the characters. But these details are the least of it. She’s everywhere in these pages, especially in the Wolgast-Amy relationship. And yes, she’s read it; she actually read it twice, the highest compliment a 13-year-old reader can pay.

The America you show, even pre-virals, is pretty grim, with curtailments on civil liberties and constant war abroad. Did the recent change in administration and in the tenor, if not the substance, of our foreign policy, affect how you depicted America in the near future? Why so pessimistic?

I began the book in the fall of 2005. This explains a lot. The war in Iraq seemed to be grinding on with no exit in sight; Katrina had just drowned New Orleans; the revelations about Abu Ghraib had badly stained America’s reputation. My mood was pretty dark. It has brightened somewhat since then, but the jury is still out.

What do you see vampirism standing in for? Is it a virus that we already know about [HIV]? Or is it about our human desires to ostracize those who are different?

To my mind the virals of "The Passage" are a kind of cultural Rorschach, the dark presence in the trees that makes us all afraid. The reader gets to decide what that is for herself. Environmental catastrophe? Scientific malfeasance? Anthrax in the morning mail? And the virals also are what they are: people trapped in the moment just before death, their individual humanity all but eradicated, waiting to make their passage.

What books influenced your writing here, other than apocalypse and vampire literature?

Behind every writer stands a very large bookshelf. You learn to write by reading, and my experiences and tastes as a reader are pretty wide. "The Passage" was certainly colored by a number of post-apocalyptic and horror stories, but I learned a great deal from writers like Dickens. One book that definitely stood over my shoulder was Larry McMurtry’s "Lonesome Dove." I think it’s the perfect example of a novel that speaks to a popular sensibility through its great characters and rousing plot while it also achieves the status of great literature. It’s also a wonderful road story, which "The Passage" hopes to be.

Could you talk a bit about "The Passage's" intertextuality? How would you describe your novel’s relationship to the texts it references through the epigraphs and the allusive character names?

I think it’s disingenuous for any writer to pretend they’re inventing the wheel, and that their book isn’t a comment on and grappling with other books -- especially when they’re writing within an established storytelling tradition, such as vampire narrative. I decided to throw my arms around this basic truth of writing and openly invoke other novels, stories, plays and poems. Some of these references are subtle, little Easter eggs tucked in the grass, and some are overt, such as the works referenced in the epigraphs (especially "King Lear," "The Tempest" and "Twelfth Night"). The list of referenced works is actually so long I don’t have space here to name them all, and no doubt there are more I’m not even aware of. They’re absolutely part of the novel and my sense of it, but the reader doesn’t need to be consciously aware of their presence to experience the story.

In the world you have created, how do you envision people telling Amy's story? As scripture? As fairy tale? As a Greek-style epic? Or as scientific text, as if she were our Lucy?

A combination of all of these. The story of "The Passage" and Amy’s journey is, for a society a thousand years in the future, the reality behind a legend, both the subject of scholarly study and something rather like the basis for a new gospel (hence "The Book of Auntie" and "The Book of Sara").

Lacey states that Lear could have nuked the facility at the beginning of the outbreak, but he held off because Amy was still there. Does this mean that the billions of deaths and the virtual destruction of terrestrial mammalian life was due to Lear’s affection for Amy? Lear must have known what the release of the virals would mean, but did he make a conscious decision to sacrifice the world in order to save Amy?

I think the question assumes that Lear was more deliberate in this choice than he was. By the time the virals broke out, he was a completely broken man, having watched his noble intentions to "solve the mystery of death itsel" perverted by the military and men like Richards. He has come to see the unfolding catastrophe as inevitable. But you’re right to note that in his final conversation with Wolgast, he suggests that Amy was a conscious attempt on his part to subvert the dark intentions of Project NOAH, so choosing not to blow the bomb would follow.

What's with the word "wicking"? It keeps cropping up. Just wondering ...

You got me there. I never noticed this.

I do have one trivial question for Justin Cronin -- what are the rules of "go to"? -- I may find myself with a deck of cards after the end of the world, and little diversion would be welcome.

I confess I don’t know all the rules. I imagine it as some combination of hearts and crazy-eights. If somebody wants to write the rules, I’ll gladly abide by them in future volumes.

Shares