The common cold makes fools of us. It’s not just the runny nose and Daffy Duck speech; it’s our naiveté about preventing, alleviating and curing the mess. Despite spending millions of dollars on preventions such as Airborne and immunity enhancers and endlessly washing our hands, we humans are still constantly undone by the minuscule menace. On average, we catch between 100 and 200 colds in our lifetime, and in the coming weeks, as the weather cools off, it will likely reduce millions to heaps of mucous and lethargy.

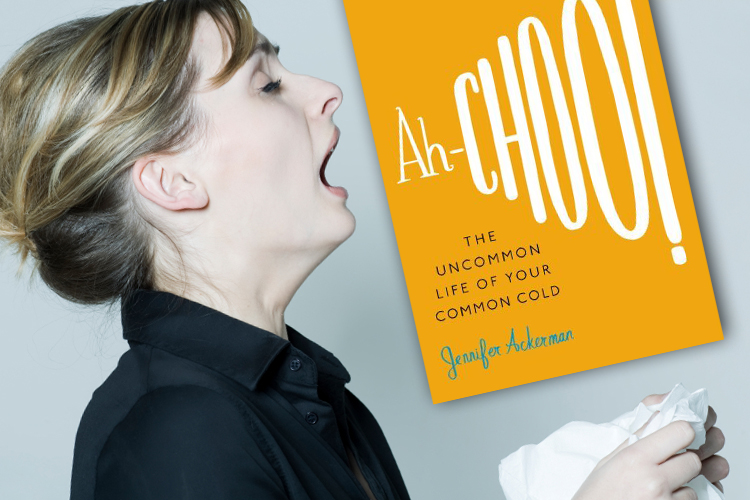

But despite its tremendous cultural presence, there are still many things we don’t understand about the common cold. In her surprising new book, “Ah-Choo! The Uncommon Life of Your Common Cold,” Jennifer Ackerman reveals what serious scientists have and haven’t learned in nearly a century of research. Ackerman, a science journalist and author of “Sex Sleep Eat Drink Dream: A Day in the Life of Your Body,” clarifies the origin of the virus name (it spreads in cold weather because we go indoors), finds out how socioeconomics could affect colds, makes connections to pandemics such as H1N1 and even considers the positive implications of being stricken.

Salon spoke to Ackerman over the phone from Virginia about the surprising science of the common cold.

Why haven’t we found a cure for the cold?

There is not just one cold virus. There are actually more than 200 viruses that make up the common cold. It’s an infection by many different viruses, but they all cause generally the same symptoms — runny nose, sneezing, coughing, malaise. With something like the flu, scientists create a vaccine based on a prediction of which strains will be most common that winter. That’s just not possible with the cold, because there are so many viruses.

Why are the symptoms similar if there are so many different sources?

I think what most people don’t know, and it’s because the finding is relatively new in the world of cold science, is that we cause our own cold symptoms. Most common cold viruses don’t do any direct damage themselves. In response to the virus, the body’s immune systems makes a whole slew of inflammatory agents, which causes the runny nose and cough.

So people who have healthier immune systems may be the ones who suffer the most?

Exactly right. One of the big myths, I think, about colds is that having a weakened immune system means being susceptible to colds. And that’s really not the case. The wisdom now is if you want to tamp down a cold, boosting any element in the immune system may be the last thing you want to do. In fact, you could create cold symptoms without injecting a cold virus at all. Just injecting the body’s own inflammatory agents will give you the symptoms of the cold. So exciting those agents, by boosting immunity, may only worsen the effects.

If it’s not a case of immune systems, why do some people get more colds than other people?

There’s a whole range of factors that affect susceptibility. Age is one of them; susceptibility declines over time. Each time you catch a cold from a particular virus, the body creates an antibody and you won’t get it again. So a teenager will catch more colds than someone who’s in their 50s or 60s. And we know that there are other factors, such as sleep and stress. People who sleep fewer than seven hours a night are three times more likely to get colds than longer sleepers. And chronic stress is another indicator for increased susceptibility.

You also found studies that show socioeconomic factors.

It’s not completely understood yet, but there’s a pretty strong correlation between socioeconomic status in childhood and susceptibility to colds. What the researcher found was that the number of years that the parents owned their own house when they were growing up was correlated with whether or not you would develop a cold when you were an adult. The greater number of years the parents owned a home, the lower your risk. And the really important years were the early years, from birth to age 6. He also did a study that shows that the perception of economic status, to a degree, predicts whether you’re likely to catch a cold.

There seems to be a debate about how the virus spreads. Were you able to get to the bottom of that question?

There’s still some debate, but clearly colds spread both by airborne droplets from sneezing and they also spread through hand-to-hand, hand-to-face contact. It depends on the kind of virus. And the most common cold virus, called the rhinovirus, most commonly spreads through nasal secretions. Cold viruses grow mainly in the nose, they multiply in the nasal cells and they are present in huge quantities in nasal secretions from people with colds. And the nasal secretions get on your hands when you’re blowing your nose, when you cover sneezes with your hands and they can spread from hand to hand with pretty brief contact.

Also, they can contaminate objects in the environment and somebody can touch that object with their hand and they can spread that way. I think what a lot of people don’t understand is if you touch that virus, you won’t get it if you wash your hands or touch your face. The way that we infect ourselves is by touching our nose or our eyes with our hands. The problem is that we touch our eyes and our noses constantly. We’re mostly unaware of it, but most of us do it up to three times every five minutes.

Those people who incessantly wash their hands with antibacterial soap are doing the right thing?

No, actually, this is a really an important point. A huge misconception in the general public is that antibacterial soaps and antibiotics in general are effective against colds. They aren’t. They’re aimed at killing bacteria. The only advantage of antibacterial soap is that they’re soap and it just helps to dislodge the cold the way regular soap does. But you have to do pretty vigorous rubbing for about 15 to 20 seconds, between your fingers, under your fingernails. And then antibiotics is another critical matter. Patients go to the doctor with a cold and they want something, because they’re miserable. The pressure on the doctor is to give them something, but antibiotics are useless against colds. The problem is that antibiotics have side effects and also the overuse can result in bacteria that are resistant to drugs.

Is there any sure way to avoid catching colds?

There’s really nothing out there that will really help you prevent getting a cold. Some, like Airborne, claim you can just take them before you go into a germy environment and it protects you. That’s a lot of baloney. One of the experts in the book said the only foolproof way to avoid colds is to become a hermit and the second most effective way is to stay away from kids. For some of us that’s practical, for most of us that’s not. So the only thing left to cut down the chances is wash your hands and don’t touch your face. And cleaning off common surfaces like refrigerator handles, microwave handles, door handles, things that people use a lot. They still don’t know what is the best cleaning solution, but they’re working on that problem.

And once you’ve caught a cold, can anything really help? Didn’t one researcher find some value of chicken noodle soup in fighting the virus?

It’s been around as a cold remedy for about a thousand years and a researcher at the University of Nebraska did find some effect in reducing the severity of inflammatory agents in cells. So, in theory, it could ease symptoms. But it’s never been tested in a clinical setting, so it remains to be proven to have medicinal value. But I’ve always felt that the warmth of the broth and the love that goes into the soup, if it’s homemade, there’s a kind of healing that’s real.

And you also make the case that catching a cold is not always bad news.

It gives us a chance to get off the merry-go-round for a few days. Because it causes malaise and it makes it so hard to concentrate, it’s a way for the body to tell you to slow down for a few days. It’s a chance for uninterrupted reading, which few of us get to indulge in the way we used to. The other possible silver lining — and these are based on very tentative, preliminary epidemiological evidence that I offer with caution — there were some results that came out of the studies on swine flu that suggest having a cold may actually keep flu at bay. This is controversial, but it is a possibility and scientists are looking at this now.

And it seems that studying the cold might be helpful in understanding other epidemics.

Right. That’s one of the reasons they are studying the common cold. If they discover something important about the cold, those discoveries may be applicable to the flu epidemic. That and the cold can be potentially dangerous in people who suffer certain kinds of asthma. So there are good reasons to study the cold, beyond the basic misery it causes and the fact that it has a major impact on the economy each year, especially with days lost in work.

You participated in one of those studies, voluntarily catching a cold. What did you gain from that experience?

Well, it was good to help with the study and also for the book. I learned that it’s mostly comprised of teenage boys who are drawn to the studies by three meals a day, a chance to stay in a hotel and the modest fee.

Did you catch a cold?

Yes, and it went straight to my chest.