I can file this one under: “Glad I don’t have a kid in Virginia public schools.” The Washington Post is reporting that a new fourth-grade textbook called “Our Virginia: Past and Present” contains a passage that states: “thousands of Southern blacks fought in the Confederate ranks, including two black battalions under the command of Stonewall Jackson.” Joy Masoff, author of more than a dozen books for children published through Scholastic Books and its subsidiaries, says she found the information through Internet research and would have gladly removed the sentence had historians asked her to take it out. (Paradoxically, she also tells the Post: “As controversial as it is, I stand by what I write. I am a fairly respected writer.”)

Had they seen the text before it was shipped out to schools, historians would have asked her to take it out. The argument that many thousands of slaves willingly fought for the Confederacy during the American Civil War has zero support in mainstream academic circles — for the simple reason that it is not supported by the documentary record. There is evidence that a very few African-Americans joined the Confederate ranks by choice; the overwhelming majority were servants and laborers.

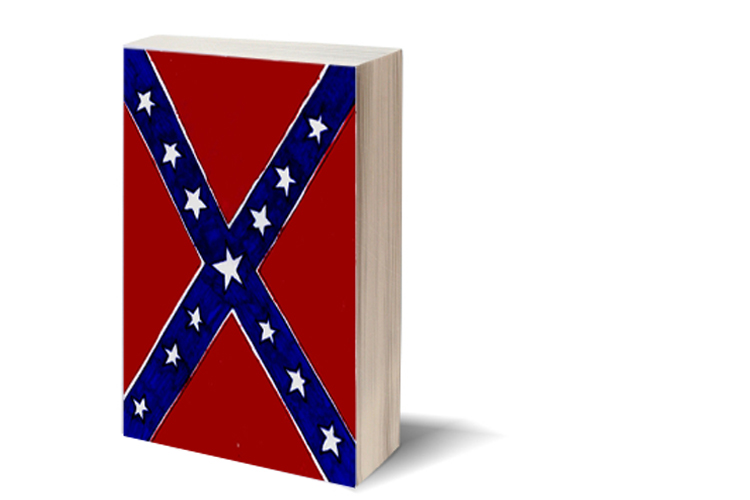

The Myth of the Black Confederate has found a home primarily in Lost Cause circles, particularly Southern heritage groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV), who use it to bolster the argument that the Civil War was not primarily about slavery. It’s been around for a while, but it has certainly found new life on the Internet in recent years. Not surprisingly, the links Masoff’s publisher provided to the Post as her sources for the passage in her book came almost exclusively from SCV-affiliate websites.

This is not to say that Ms. Masoff is some sort of pro-slavery apologist. As far as I know, she’s a nice, middle-aged lady from New York — Westchester, to be exact — who has published way more books than I have and asks a speaker’s honorarium of $1,000 a day plus expenses. Clearly, though, she let what she perceived as an “interesting fact” from the Internet override a huge body of historical scholarship, and in doing so, helped propagate a dangerous storyline: that slavery was not the major issue of the Civil War.

Ultimately, the failure is not Ms. Masoff’s alone. The editors and the academic advisory board at Five Ponds Press let it go to print without properly evaluating the statement. The Virginia Department of Education, which just issued an advisory to teachers using the textbook to simply ignore the passage, says in a statement that “just because a book is approved doesn’t mean the Department of Education endorses every sentence,” … even though that’s sort of the point behind passing the book through their panel of teachers and content specialists, who rated the book “accurate and unbiased” during the evaluation phase.

In a publishing industry ravaged by the recession and the rise of the e-book, educational books still represent major money for publishing houses. Work is outsourced, sometimes to nonspecialists, and usually done on the kind of tight deadline that makes it difficult for editors and advisors to properly vet the text before it heads into the printing phase. The race to produce titles for schools inevitably leads to these kinds of factual and interpretational errors slipping through what looks like a strong safety net.

I speak from experience. As a contributor to more than a dozen reference and young-adult titles, I can tell you the voracious demand for text often forces writers to work at maximum speed, with minimal contact with editors and academic advisors to try to nip errors in the bud … or at least catch mistakes before the galleys are set. To my knowledge, I have committed no factual errors to print. But I know it could easily have happened, unnoticed, and I still would have gotten paid.

The morals of the story are simple.

Writers: Verify, verify, verify. Then verify some more. The Internet is not the ultimate source of human knowledge.

Parents: Read through your kid’s textbooks and give them the old smell test. If something seems to stink, follow it like a bloodhound back to its source. And if it’s foul, raise hell.