Making narrative out of a life like that of Crazy Horse presents the biographer with a daunting set of challenges. Shrouded in the mythology of the West and the mystery of his indomitability, Crazy Horse is a shadowy figure, whose exploits took place almost entirely on the inaccessible side of the Sioux Wars’ bloody line through history. It’s for these reasons, and the Wild West timbre of his name to 20th-century ears, that he became a kind of brand, a 19th-century Che Guevara of the North American plains. And yet among the Sioux, his presence is keenly felt: There are still a few alive old enough to remember seeing and speaking with those old enough to have laid eyes on Crazy Horse.

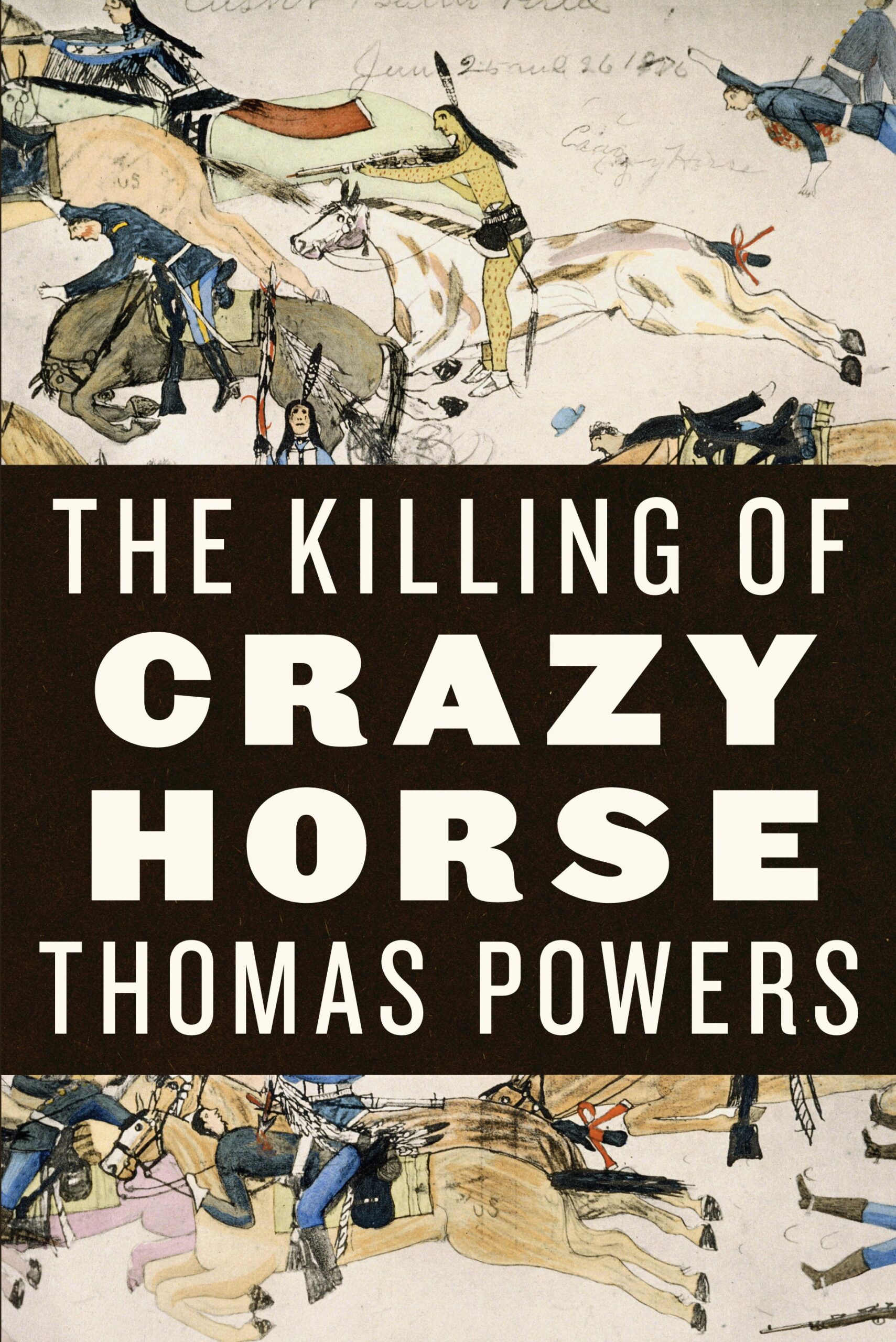

“The Killing of Crazy Horse” takes on the mythology and the history of the man and his age. Thomas Powers — whose work as a journalist peering into the shadows of the intelligence world has served as surprisingly apt preparation — nimbly traces the mixture of legend, tacit knowledge, and hearsay that represents the canon of Crazy Horse studies. The Sioux Wars of the 1860s and ’70s comprised a world with a social structure all its own. Even for the Sioux, the plains were a relatively new domain. They had not made their home there until they embraced the coming of the horse to the Americas in the late 18th century. Like the Comanche in Texas and Mexico, the Sioux would ride the horse to hegemony, creating what the historian Pekka Hamalainen has called an “equestrian empire,” co-opting some tribes, like the Cheyenne, while beleaguering others, earning the enmity of the Pawnee to the west and bringing the Mandan — a peaceable tribe who welcomed Lewis and Clark and who figure heavily in the art of Karl Bodmer — to the brink of extinction. It was their power, burgeoning and resented by their neighbors, that brought them into conflict with the white pretenders to the plains.

“The Killing of Crazy Horse” takes on the mythology and the history of the man and his age. Thomas Powers — whose work as a journalist peering into the shadows of the intelligence world has served as surprisingly apt preparation — nimbly traces the mixture of legend, tacit knowledge, and hearsay that represents the canon of Crazy Horse studies. The Sioux Wars of the 1860s and ’70s comprised a world with a social structure all its own. Even for the Sioux, the plains were a relatively new domain. They had not made their home there until they embraced the coming of the horse to the Americas in the late 18th century. Like the Comanche in Texas and Mexico, the Sioux would ride the horse to hegemony, creating what the historian Pekka Hamalainen has called an “equestrian empire,” co-opting some tribes, like the Cheyenne, while beleaguering others, earning the enmity of the Pawnee to the west and bringing the Mandan — a peaceable tribe who welcomed Lewis and Clark and who figure heavily in the art of Karl Bodmer — to the brink of extinction. It was their power, burgeoning and resented by their neighbors, that brought them into conflict with the white pretenders to the plains.

Despite the differences that separated them, by the 1860s the worlds of whites and the plains tribes were intimately intertwined. An entire generation of “half-breeds” had emerged, the offspring of white trappers and traders and Indian women, whom the Sioux incorporated into their already flexible notions of family. One of the most colorful of these figures, Frank Grouard, had no Sioux blood. Born near Tahiti, he was the son of a white missionary and a Polynesian woman. As a young man, Grouard made his way to North America, found himself living among the Assiniboine, who were enemies of the Sioux. Captured by Hunkpapa warriors, he was delivered into the hands of none other than Sitting Bull — who adopted him and taught him the Lakota language. Grouard moved fluidly between Indian and white worlds, even taking an active part in hostilities on both sides of the Sioux Wars. Another of these men, Billy Garnett, would serve as an interpreter for Gen. George Crook and other U.S. authorities throughout the Sioux Wars. But having witnessed the killing of Crazy Horse, Garnett would choose the Sioux world when the tribes were forcibly relocated east of the Missouri River; today, his descendants live near the Pine Ridge Reservation, where they still speak Lakota.

The tapestry of the Sioux world in the 1860s and ’70s was varied and paradoxical: Many bands lived full-time at agencies established by the U.S. government, where life was a bizarre pageant and a simulacrum of older ways; soldiers would release beef cattle one at a time for the Sioux to ride down — as if the domestic brutes were wild buffalo. But some bands and families still left seasonally to hunt and live on the open plains. Still other bands, the so-called Northern tribes led by Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and Gall, refused to come to the agencies and relinquish the beloved, forbidding Black Hills, where rumors of gold would set in motion the chain of events that led to the Battle of the Little Bighorn and, ultimately, the dispossession of the peoples of the plains.

By the mid-1860s, when Crazy Horse’s exploits as a warrior were first gaining him notoriety among his own people, the Sioux position as the power of the plains was under assault from white settlers. Open hostilities broke out upon establishment of the Bozeman Road, which ran through tribal hunting territories on its way to the gold fields of Montana. Under the leadership of Red Cloud, Sioux bands went to war against the whites; on the solstice in 1866, Crazy Horse, then in his mid-20s, personally lured a force of 80 soldiers into a massacre behind a ridge near Fort Phil Kearny.

To his peers as well as to later generations, Crazy Horse was an enigma. “Most Sioux scalped enemies,” Powers writes. “But Crazy Horse did not take scalps, nor did he tie up his tail before battle with fur, feathers, or colored cloth as other warriors did.” Despite his many war honors, he never wore more than a couple of feathers. And his plainness in ornament was matched by plainness in speech. Oratory was a prized skill among prominent Sioux men, but in council, Crazy Horse usually had friends speak for him.

His nemesis on the plains, Gen. Crook, was the mirror image of Crazy Horse. Like the Sioux chief, Crook was a talented hunter and a taciturn leader. But unlike Crazy Horse, Crook’s quiet manner hid a resentment born of thwarted ambition. Crook led and fought valiantly throughout the Civil War, yet credit for his successes repeatedly fell to his friend and West Point classmate, Gen. Phil Sheridan, who now commanded him in the West. To Crook, the quiet charisma of Crazy Horse was more than an irritation; it was almost a taunt. The serially thwarted general privately stewed as his superiors judged him and the press skewered him; Crazy Horse remained equally silent, and his stature only grew.

Crazy Horse and his allies fought Crook to a stunning draw at the Rosebud; in barely a week, on the eve of the U.S. centennial, many of the same warriors would rub out George Armstrong Custer and his men near a creek the Sioux called the Greasy Grass. Powers’ expository history of the campaign leading up to the fight at Little Bighorn is fluid and authoritative, although he indulges in a bit of the unavoidable armchair trivia-chopping students of the battle long have practiced. But in its telling of the final day of Crazy Horse’s life, Powers’ account approaches the austere hopelessness of Greek tragedy, as the chief finds himself resented, friendless and mistrusted, caught between the aspirations of his peers and the impatient fear of the white soldiers into whose hands he had fallen. His end, shocking and implacable, was spelled out in Crook’s imperiousness, Frank Grouard’s duplicity, and the incomprehension of soldiers and officers in charge of him.

Throughout this magisterial work, Powers captures the complexity and contradiction of the world of the Sioux Wars, and its terrible beauty as well. After a chapter spent describing the war magic of Sioux fighting men on the eve of battle, Powers concludes:

[This] is what rode south toward the Rosebud on the night of June 16–17, 1876: thunder dreamers, storm splitters, men who could turn aside bullets, men on horses that flew like hawks or darted like dragonflies. They came with power as real as a whirlwind, as if the whole natural world–the bears and the buffalo, the storm clouds and the lightning–were moving in tandem with the Indians, protecting them and making them strong.

“The Killing of Crazy Horse” should stand alongside “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee” for the authority and art with which it recounts this moment in a people’s shattered history.