A friend once told Eleanor Coppola, "Life is like knitting an argyle sock. You can't see the pattern until you're nearly finished." In her new book, "Notes on a Life," Coppola takes up the work she started 30 years ago in "Notes on the Making of Apocalypse Now": her struggle to establish her own professional identity in the dynamic, engulfing world of America's first family of film. It's a battle that she often seems to be losing, but by the end of her second book, as she nears the age of 70, the threads of an artistic life stitched together in starts and fits emerge into a beautiful, integrated pattern.

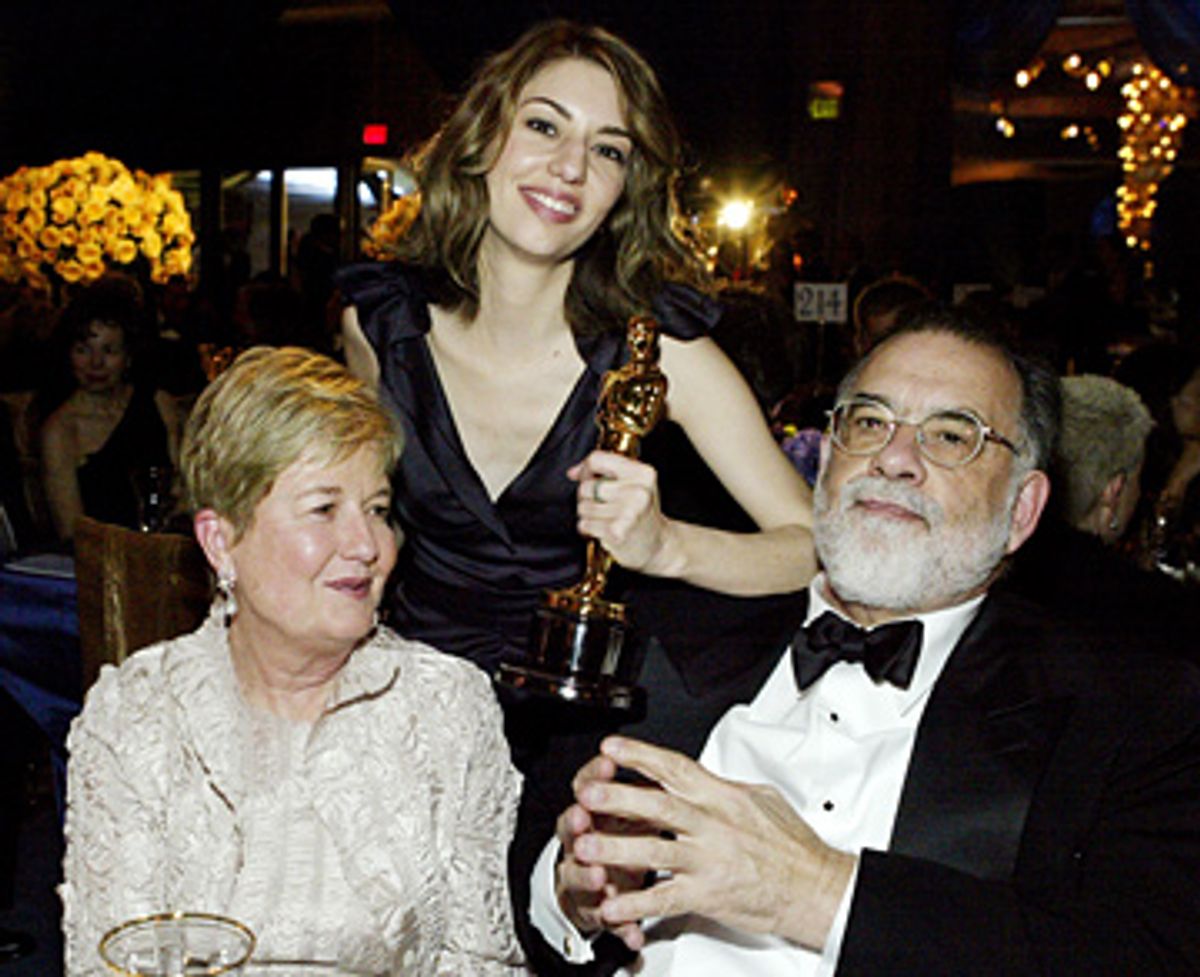

"I am an observer at heart," Coppola tells us in the opening of "Notes on a Life," and her honest and ironic takes on celebrity from its fringes are sometimes reminiscent of the reporting of Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski. When Marlon Brando charms her on the set of "The Godfather," she writes that it was "as I imagine a hit of heroin to be: stunning, short-lived and dangerously seductive"; later he ditches her when she has arranged to interview him for her documentary on "Apocalypse Now." (By contrast, Kevin Costner's deliberate attention to her when they meet suggests to her that his wife trained him to understand "how uncomfortable it is to be the invisible person.") When the family is photographed after one of her proudest moments as a mother -- when Sofia, accepting her best screenplay Oscar for "Lost in Translation," thanks her mom for her encouragement -- the only trace of Eleanor in the newspaper photo the next day is her elbow.

Part of the tension in the book comes from the seeming contradictions in Coppola's life: She is a soft-spoken, introspective artist married to one of the world's most flamboyant and ambitious filmmakers; a mother who longs for solitude yet feels left out when not with the family; a wife who deals with mundane domestic tasks while the rest of her family is in the exciting throes of filmmaking wizardry; a millionaire several times over who was raised to write grocery lists on the clean insides of used envelopes for thriftiness.

Coppola was raised in the small town of Sunset Beach, Calif. Her father, a political cartoonist for the Los Angeles Examiner, died when she was 10; her mother, a housewife, was more interested in books than housekeeping. (Eleanor's teenage rebellion was "baking perfect lemon meringue pies, sewing all night, and working two summer jobs.") She met and began dating Francis Coppola in Ireland when he was directing the Roger Corman splatter film "Dementia 13" and she was an assistant to the art director. In 1963, several months into their relationship, she discovered that she was pregnant and considered giving the baby up for adoption. But Francis was ecstatic: "I've always wanted a family," he said, and the couple was married the next weekend. Another child followed soon after, leading her to write, "My life was shaped by pregnancy." In 1986, her son Gian-Carlo was killed in a horrific boating accident. The Coppolas immediately took in his girlfriend, Jacqui de la Fontaine, who was two months pregnant at the time, and they found solace in the gift of a granddaughter, Gia.

Outside of her book and documentary about the making of "Apocalypse Now," "Hearts of Darkness" (co-directed by George Hickenlooper and Fax Bahr based on her footage) which won several awards, Eleanor Coppola is relatively unknown for her own work. Her early artwork in the '70s included conceptual installations with artist Lynn Hershman Leeson in a fleabag hotel above the Broadway strip joints and in the Coppolas' 22-room home in San Francisco. Playing on the idea that many visitors to the latter came mostly to see a famous filmmaker's home, she removed his five Oscars from their glass case and replaced them with the miniature Oscars given to the winner's wife to wear as a necklace. She also paid Sofia and son Roman to stay in a bedroom where a TV played a video of Sofia's birth and a sign read: "The author's most important work, expected to take 21 years to complete."

But it seems that it was after the death of Gian-Carlo that she truly found her voice in "Circle of Memory." The installation consists of a circular chamber with straw bale walls, where salt falls in a thin stream into a glowing mound in the middle of the room and a soft wash of children's voices recite the alphabet. Visitors are invited to call up memories of children who are missing or who have died, and write messages to insert in the walls. The installation broke attendance records at the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego, where it was first exhibited.

For many women, one of the most fun aspects of reading Coppola's new book is discovering how much of her life seems like ours -- albeit in more spectacular settings. She gets caught up in stupid arguments with her kids, eavesdrops on their conversations in carpools, brings a Tupperware of chocolate chip cookies to Sofia on the set of "Marie Antoinette" when she is worried that her daughter is getting too thin. Doing mundane household chores, she admits that she sometimes feels "as if my brain is a rusting file cabinet full of useless information." Yet she persists and ultimately triumphs. For any woman who is struggling with career and family, or whose husband's work always seems to take precedence over her own, "Notes on a Life" is a bittersweet portrait of modern American womanhood.

I spoke with Eleanor Coppola on a soft, breezy day in early summer on the porch of her 1885 Queen Anne Victorian in Napa Valley, as we sipped glasses of spring water and nibbled on cookies from a plate neatly pressed with a single forget-me-not stem.

You met Francis on the set of his film "Dementia 13," where you were both working. Why didn't you continue to work together in film?

I thought we were going to be working together, and that he was going to make these little low-budget, Roger Corman black-and-white films. In fact, I went on the next film with him and I was making sets, and then I discovered I was pregnant and we got married. We had two children back-to-back, and by the time I was ready to go back to work and wanted to work, his career had advanced way beyond me. The people he was hiring were professionals; they weren't just friends and everybody kind of helping out.

That kind of left me in this limbo because we had a deal that if he was going to be gone more than two or three weeks, we'd take the whole family on location. So that, of course, uprooted me to go with the children and cut off projects that I might have started outside the family. When we got to "Apocalypse Now," and I got this idea to shoot a documentary, it was a lifesaver because it gave me a form of expression on these locations where everyone else is engaged in some creative process and I'm the one shopping for the mop.

In the book, you are often shopping for mops and trash bags and doormats. Why didn't you hire somebody to do those kinds of things?

I came from a background that didn't prepare me for the kind of life that we were living in. Francis did too. My mother never had a cleaning lady, his mother never had a cleaning lady; his family never had a nanny, my family never had a nanny. I didn't know how to find the person who could come in and shop for these things that I needed -- it would be faster if I just went and did it myself! I should have gone to hotel school or something -- there I was, the mistress of this 22-room house and this place out here, and I came from a house with one bathroom. I just didn't have a clue.

It seems that you have a lot of input into his creative process. Is this true?

I don't think about that because I have that kind of dialogue with a lot of creative people I know. I just say what I'm thinking and there's a lot of back and forth. He's pretty focused and single-minded. I'm not one of those creative partners with him, not one of his collaborators. Maybe I'm the audience.

At one time, in the '70s, he asked me about a particular part of this project he was working on. I thought, Oh I'm his muse, I'm so important! Then the next day I was down in the kitchen and he was asking the baby sitter the same thing. So I know he just uses whoever is around as a sounding board, and I'm part of the sounding board.

You wrote about your discomfort when Diane Keaton told you she had modeled the character of Kay Corleone in "The Godfather" on you. What did you find so repugnant about that?

I thought that character was completely repressed by the family. I identified, of course, with the WASPness of this person in this Italian environment, but she didn't come out of it that well. I wasn't wanting to be the model for that, but I also understood her seeing me as the WASP woman in this Italian family.

Francis was criticized quite a bit for casting Sofia as Mary Corleone in "Godfather III," and you were criticized for letting him do it. Some people actually called it "child abuse." Do you think that it was good or bad for her to go through that experience?

At the time, I didn't know if it was going to be good or bad. After the fact, I think it was a good life lesson. It taught her how to stick with it through a really hard experience and do the best you can, even if it's not easy and even if not everybody likes you or likes it. That's one of the great things that our kids learned from Francis -- that it gets hard and then it gets harder and it still gets harder and you keep going and it gets harder and you keep going. You don't just stop or give up. It's part of the creative process: having the will and the ability to stick with it when it's hard. It's easy to do it when it's fun and thrilling, but to stick to the hard part.

When your children were growing up, you worried about how your unconventional family life would affect them. Looking back now, what do you think?

It cuts a little bit both ways. Mostly I think it's been good for them because it's given them a comfort in the world. Both Sofia and Roman shot films in Europe and they were totally at ease doing it. I know some kids who grew up here in Napa and moved to San Francisco, and it was too much traffic and too many hills and they moved right back. So I think it's given them access to the biggest possible canvas, and that part is really good. Of course, they missed some of keeping up on their Little League or whatever you miss when you leave a lot.

In the book, you write that you often said to Sofia when she was growing up, "Everyone is going to expect you to be a spoiled brat. Please surprise them." Your children are certainly not slackers. How did you manage that?

It helped not to live in Hollywood, and that they were growing up here, in what was at the time an agricultural community and small town. I like it that they both come back and see friends they went to school with -- that they feel a connection to their roots.

I was constantly trying to figure out how to keep them well-behaved because, of course, we stayed in hotels when we traveled a lot, so my kids ate in restaurants a lot and threw their clothes around, and the maids cleaned up after them. But I think they got a good work ethic from Francis because he is an extremely hard worker. There was just the pleasure of working. Roman worked on his first film when he was 16. We also had these financial ups and downs, so there was always sort of the unmentioned fact that "you know, we could be in a down moment when you mature and you're going to have to take care of yourselves."

You have written about your marriage going through some pretty tough times. Why did you stay with Francis?

I feel like that's kind of old news, so I'd like to keep focused on this book, which is not about that.

How has your relationship with Francis changed over the years?

We've both gotten more accepting of each other. He's gotten more accepting of my projects. You can see that in the book. He was disapproving of that conceptual art thing in our home, but he was approving of the Circle of Memory project -- you see him coming to it at the end, bringing Gia and being supportive. So it's just evolution.

At one point in the book, while you were in Paris with him when he was doing the publicity for "Rainmaker," he tells you that he must work that day, but you are free. The remark upsets you and later that day, on the Pont Neuf, you actually consider jumping off the bridge. Why were you at such a low point?

I was being pulled away again from what I wanted to be doing. It looked so glamorous to everyone else: I'm sitting in Paris and my husband says I don't have to work, and all of the conventional wisdom is saying I should be happy as all get-out. And I am not happy, and it has to do with not being able to do the work of my heart in that circumstance.

Because of the way you were raised, and the tension you felt between work and family, were you determined that your daughter be an independent woman?

Because I loved art, I always had an art table in the kitchen and a lot of paints and clay and paper, and Sofia just took to it like water. I thought it was because she was a girl; I didn't know it was just her. So I did encourage that. And I think because I wanted that independence myself, I tried to make her feel that she could do anything she wanted; that there was no stigma about being a girl.

When your son Gian-Carlo was killed, you wrote that you were "as angry as you could be." How did that anger come out and how did you come to grips with it?

I was filled with anger and I knew that I didn't want to hang onto it because it's poisoning your system. Intellectually, you know that in the bigger picture, there's life and death, and chaos and order, and accidents and triumphs, so you know that you need to integrate it. That's another treasure about Napa. I knew that I could just walk down these dirt roads and scream my guts out and no one would hear. I was free to just release the emotion in me.

Before Gio's accident, my emotional life -- the range of the highs and the lows -- was smaller. After the accident, my lows went way down, and you're lost down there for a while until you begin to recover. And then you realize that your highs have gone way up too: your ability to appreciate the children that you do have, the days that you do have, this grandchild that we did receive. It extends on both ends.

A lot of couples split up after a child's death.

Ninety-two percent of couples do.

Did Gio's death bring you and Francis closer?

In the long run, but in the beginning it's just too difficult because everyone grieves in their own way. But finally, you're the only two people who have those memories together -- of your children, your family.

What did you get personally and professionally from doing "Circle of Memory"?

Personally, I liked the integration of my life and my art. Sometimes in art, you do something that's outside of you, but that was a way to express my life experience. Professionally, it was well received. It's been in three cities in the states, and the south of France last summer, and it's going to Salzburg this summer. It has a profound impact on people who visit it, and it's a neat thing that I'm setting an environment for people to have their own experience. Some people remember children there. One woman said, "I sat down in there and my father started to speak to me." So it's whatever you bring to it. And I like that better than saying, "This is art and you need to look at it this way." It's a container for your own experience.

You write at the close of the book that you are happier than you've ever been. Why?

As the years go by, you just learn more, so you know what you need for yourself. I'm just more aware that I need to do this creative work, and Francis got used to the idea, and the kids were gone, so I had more time to do it. The more self-satisfied I was with that, the more pleasant I was as a wife. I think we just learn how to be more adept at our life's path, so to speak.

You've said that you kept a journal to "explain yourself to yourself." But why did you decide to share so much private and honest information about your life with the public?

That's a question I have a hard time answering even for myself. But once I've written it, once it's in the manuscript, it's not connected to me anymore, and I feel pretty detached from it. It could be somebody else's story -- like a book I'd like to read if somebody else wrote it.

Shares