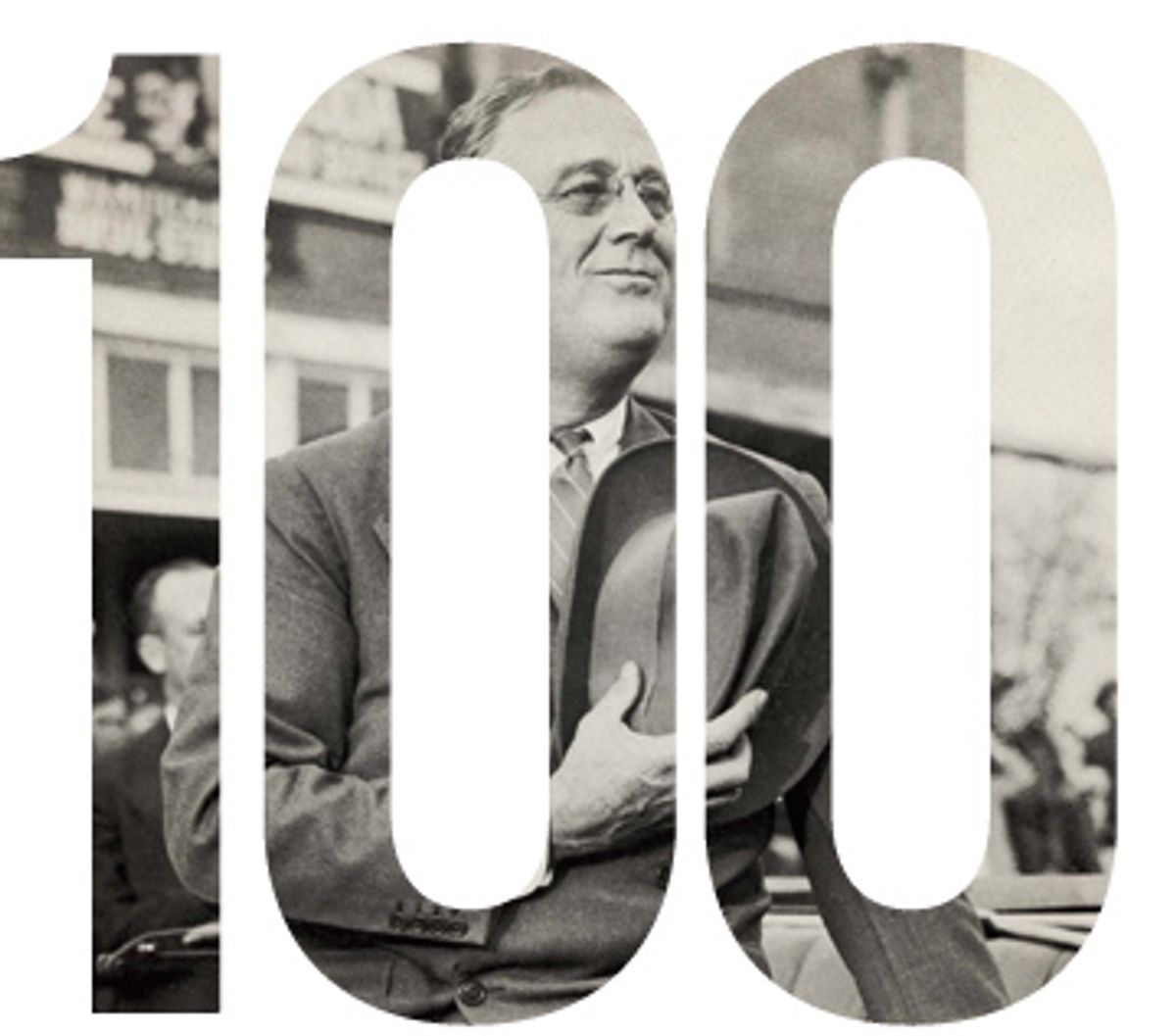

According to an article in Monday's New York Times, Barack Obama, a week away from the presidency, is trying to learn from a predecessor who also entered the White House at a time of national crisis. Aides say that Obama has studied FDR's first 100 days, "even look[ing] at the words Roosevelt used and the tone he struck," in hopes of emulating the way FDR carried on a "conversation with the American public" and built confidence in the New Deal.

But if Obama wants to know how the New Deal was actually forged, New York Times editor Adam Cohen's book "Nothing to Fear: FDR's Inner Circle and the Hundred Days That Created Modern America" is an indispensable primer. According to Cohen, the original New Deal, which forever transformed the role of the federal government, was not born out of the sort of patient planning for which Obama is known. In a phone interview, Salon asked Cohen, an assistant editorial page editor at the paper, to draw comparisons between Obama and Roosevelt, and between 1933 and 2009.

It's one week before the inauguration. What were FDR and his "Brain Trust" doing at this point in time -- a week before March 4, 1933? And how does that compare to the Obama transition?

The Obama transition is really impressing me right now compared to Roosevelt's transition. Roosevelt had a "Brain Trust" during the campaign that was working on policy ideas, and this continued after the election. There were definitely a lot of ideas floating around, but in early '33, the New Deal was still very undefined. So, we had some general sense of various things he talked about during the campaign, but some of them were in conflict: The idea of cutting spending tremendously but also trying to help the people that had been injured by the Depression. Doing something about the crisis in the farm belt, but we didn't know what. So the story of FDR's first hundred days is really the attempt to put some meat on the bones of the New Deal. The infighting, the ideological conflicts [meant that] by this time in 1933, much was up in the air.

I think we are seeing more clarity from Obama. We're seeing him talking before he takes the oath of office about stimulus and job creation in a way that shows a little bit more focus and direction.

What are the differences between 1933 and 2009 in terms of how much worse things had gotten between election and inauguration? In 1933, the gap was five weeks longer because FDR wasn't inaugurated until March 4. In the book, there seem to be some eerie parallels, like some of the worst financial problems being centered in Michigan, with banks failing there, and autoworkers being affected. How much more of a crisis was March 4, 1933, than November 1932?

Some of this is hard to measure because the Great Depression was so bad that there is bad, bad and bad, bad, bad. But the big thing that did change between the election and the inauguration was the bank failures. And that was a big deal. There were runs on banks but also, state by state, banks began to fail and banks began to declare bank holidays to the point at which, the night before the inauguration, the last two states declared bank holidays and literally all the banks in the country were closed. So it was really that banking crisis that was the big differential between November and March against the backdrop of very high unemployment and industrial slowdown and all that. That's why when FDR takes office, the first thing he deals with is that Emergency Banking Act. Because that was the crisis of the moment.

How conscious were you of historic parallels while you were writing and researching the book? I imagine you conceived of this project long ago, at a time when it was probably clear that the housing bubble might burst but long before something like the collapse of Lehman Brothers made the economic calamity really apparent.

I decided to write the book in the middle of the Bush administration. And that's right, there was no sense yet of the economic crisis, no sense yet that there would be the election of someone like Barack Obama, who in many ways is modeling himself on FDR. The impetus for the book was that in the middle of the Bush administration, a war had been declared on the New Deal. There were conferences on rolling back the New Deal. President Bush began his second term with an attempt to privatize Social Security. I felt that if you wanted to look for a distant mirror in history for what was happening at that moment, the New Deal was really what we were fighting over in the middle of the Bush administration. So I wanted to go back and look at, What was the New Deal, where did it come from, what was the reason for it? But of course, the more I was working on it, the more modern events began to catch up with it.

I did believe that there were a couple of things the New Deal did that were very relevant to today. One was the creation of the social safety net, which was I feel in general is very important. I was troubled that there was such an attempt to undo Social Security, and then also I did have a sense that the deregulation of the Bush administration was a dangerous thing. I knew that the New Dealers had created a regulatory state. They did it in order to impose reasonable rules on capitalism, and I, without knowing specifically that there would be a mortgage crisis and that would lead to economic calamity, I had a sense that deregulation was taking us in a very bad and dangerous direction and therefore wanted to look back at when were all these regulations put in place. Why did we feel like we needed them?

I was writing at a time when the question was almost, Can the New Deal be saved? Has it become so unpopular with the people who wield political power that it can't be saved? The book comes out at a time when everyone is saying, "Can we get more of that New Deal? We need a lot of New Deal now." Yeah, it was an amazing turnaround, but that is the turnaround that we as a nation experienced in the difference between when Bush was reelected in 2004 and Obama being elected. We've made that huge U-turn as a nation.

Not everybody has made that U-turn. I keep coming across people rearguing the New Deal on right-wing Web sites. There was something the other day from Kathryn Jean Lopez on the National Review online, where she posted a chart that supposedly showed that FDR hadn't done such a good job in bringing unemployment down.

This is a big right-wing talking point right now. If you watch Fox News it comes up a lot, too. It's this idea that FDR actually prolonged the Great Depression. Amity Shlaes kicked this off a couple of years ago with "The Forgotten Man", which was a revisionist take on the New Deal. That is something they're talking about now. But it's also been pretty strongly debunked. There are several Web sites debunking a lot of it. [Paul] Krugman has been writing about why it's not true. I think people now -- right-thinking people -- agree that FDR did improve conditions during the Great Depression and in fact if he had been willing to spend more, to be more New Dealish, more deficit spending, more Keynesian economics, he would have even ameliorated the problem more quickly. It was his timidity and his famous decision in '37 and '38 to try to cut down on spending, which caused another recession. Those revisionist, anti-New Deal ideas are out there, but I don't think they're correct at all.

What's at stake for the people advancing them?

A couple of things. I think originally what was at stake was this idea of unraveling the safety net, unraveling social programs. So if you say that the New Deal didn't do any good, it made things worse, then that provides ammunition for people who want to privatize Social Security, reduce welfare spending, things like that. That has less traction right now because of the economic times we're in. But there is still an attempt to stave off regulation, right? There's a sense now that we're going to get a lot more regulation when people see how badly things went in the deregulatory age. They want to stave that off. And then also, there are a lot of people who don't want Obama to do a very large stimulus package. So, one way they can try to fend that off is to say, "Hey, we tried that in the New Deal. It made things worse."

It would also be historically inconvenient if the same remedy worked twice.

Yes.

When you were looking at FDR's first 100 days, what surprised you about them?

A couple of things. One is I had this sense that it was a program, a plan, that was carefully implemented. And the degree to which it was improvised was striking. How we end up with the federal welfare program that we ended up with. Literally, Harry Hopkins, who was a state welfare administrator in New York state, has a really ambitious plan that involves a lot of federal spending, federal standards. He can't get into the White House to sell it to FDR. He calls up [Secretary of Labor] Frances Perkins. She meets with him quickly before dinner under the staircase at the women's club where she's temporarily living. She says, "This is a great plan. I'm going to sell FDR on it." And she does, and that's how we get the Federal Emergency Relief Administration. That kind of spontaneity was really striking.

And the other thing was the lack of ideological agreement. There actually were conservatives in the mix who were fighting all this stuff and it was not foreordained at the beginning of the hundred days that there would be public works. FDR's budget director, Lewis Douglas, opposed them, and even FDR [initially] opposed public works. It was really a conversation and a battle to get a lot of these things.

One more thing, which is one of the main points of my book, is the degree to which -- although FDR was a brilliant communicator and a brilliant politician and an inspiring leader -- so much of the substance of the hundred days, the policies that emerged, came from his inner circle, from the people around him and people like Harry Hopkins, Frances Perkins, Henry Wallace, who I think have not been given the historical credit that they're due.

You talk about it as a sort of team of rivals, of adversaries, but it sounded more like a group of liberals -- Wallace, Perkins, Hopkins -- versus [budget director] Lewis Douglas, with [presidential advisor] Ray Moley as a referee. So that there was an ideological momentum of sorts in the administration, with Douglas trying to check it.

Yeah, although, it's interesting that Douglas really was the star of the early days. After they got the Emergency Banking Act through, which they had to do to get the banks open, the first thing FDR does is the Economy Act, which is Douglas' plan to cut the federal budget by 25 percent. And Douglas is the golden child of that moment. FDR adores him; he's telling people he thinks Douglas should succeed him as president when he's done. And it really took some doing for the liberals to end up on top. They were not at the beginning, and I don't think it was inevitable that they would rise and Douglas would fall. But that's how it worked out.

You write about the House Republican leader urging a yes vote on the Emergency Banking Act, Roosevelt's first piece of legislation, without reading the bill. And you also talk about that act essentially being finalized, written and passed and signed, in the space of about 24 hours. I cannot imagine the current Congress on either side of the aisle behaving in that manner. The Democrats are already balking at Obama's stimulus ideas.

I mean, yes and no. We saw not an identical but an analogous rush with the Patriot Act, which, when that was passed originally, after Sept. 11, a lot of folks had not read it. So I think that we're not immune from that now. I do think, though, there's going to be more obstruction from the Republican side of the aisle now than FDR saw. During FDR's first hundred days, the Republicans were almost as willing as the Democrats to say, "We're going to trust this new president to lead us, and we're just going to support him in almost everything he does." But part of that is that times are not yet as terrible. We're just getting the new unemployment numbers, which are bad, very bad, but they're not 25 percent. And our banking system has not collapsed. We're not entering the third year of a Depression. So I think that if things were worse, there might be more of that feeling of "Defer to the president." But right now I think Obama is going to see a fair amount of opposition in Congress.

How about the presidents? How does Obama compare to Roosevelt in temperament and intellect?

There are many parallels. For one thing, they are both very charismatic, very good communicators. They're very good politicians in the sense of being able to put together winning coalitions. I think Obama is in some ways more substantively knowledgeable about some of the issues he's dealing with. To a striking degree, FDR didn't really know a lot about the specific problems he was addressing. And often didn't care about the details as long as he thought it was a good plan. I think Obama will be more into the details, the nitty-gritty, and will be sort of delving into the substance more than FDR did. But I think that there's a reason that Obama is starting to model himself on FDR. In many ways they're similar: optimistic, skilled at politics and pragmatic.

How is the public different today than 76 years ago? There was a recent article by Michael Massing in the New York Review of Books, in which he goes to Toledo, Ohio, Joe the Plumber territory, during the run-up to the election, and he keeps coming up against a "strong strain of stay-out-of-my-way self-reliance" that breeds distrust of government intervention. That kind of culture of self-reliance might make it difficult to get the sort of sweeping government programs and government intervention passed that are needed in times of crisis. I was wondering how you think the country or the mood of the country compares now to the mood of the country in the first hundred days of the Roosevelt administration and specifically their receptivity to this sort of sweeping action?

I think that kind of self-reliance is generally the first casualty of a Depression. Hoover was a great believer in rugged individualism: He wrote a whole book about it. He believed exactly in self-reliance. He thought that government spending on social welfare programs was injurious to the recipients, and it damaged the moral character. But when the hard times hit, the American public, who had once supported that, turned away from that very sharply and did not reelect him and turned to Roosevelt, who presented the alternative model. I think we're going to see that soon even in places like Ohio. People who think they believe in self-reliance, when times get really tough, they realize that they or people they know well need help and are more open to strong government role. So I think that if the economy continues to weaken, I don't see that as being a big problem over time. I think people will change.

I was interested in the instances you cite of President Hoover trying to influence policy in the incoming Roosevelt administration, but also being obstructive. Did that continue throughout the FDR presidency?

Yes. Hoover was a sort of negative voice on the New Deal. And would occasionally mouth off about how people had made a great mistake and they were sacrificing their freedom. But for the next three years, there really was not much of an appetite for that, because people believed in FDR and the New Deal, and that's why in the '34 midterm elections, the Democrats gained seats in Congress, and in '36, FDR was reelected in more of a landslide than in '32. So yeah, Hoover was picking at the New Deal from the sidelines, but he didn't really make that much of a difference.

Shares