Over the weekend, a momentous game of chicken took place in the book industry. As the dust clears, it looks like the world will be a much less friendly place for Amazon.com’s e-reader device, the Kindle.

After negotiations on e-book pricing between Amazon and publisher Macmillan broke down on Thursday, Amazon retaliated by removing all Kindle editions of Macmillan books from its online store. It even went so far as to stop direct sales of the print editions of Macmillan titles, as well. (Customers could still buy the print books via Amazon, but only through third-party sellers and without the minimum-order shipping discounts and other benefits of buying directly from Amazon.) Sunday night, a posting from Amazon’s “Kindle Team” announced that the company would capitulate to Macmillan’s demands, but as of this writing, you still can’t buy such bestsellers as Hilary Mantel’s “Wolf Hall” or Robert Jordan’s “The Gathering Storm” from Amazon in either Kindle or print editions.

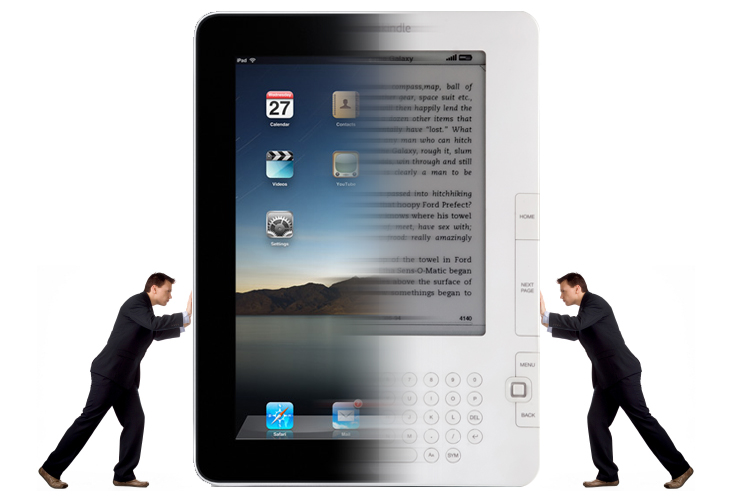

This dust-up is the culmination of a long-standing feud between Amazon and book publishers. What triggered it, however, is something new: the introduction of Apple’s iPad.

Publishers have hated the Kindle since it was introduced because they believe Amazon is using its clout to artificially force down the price of e-books. Amazon retails the Kindle editions of new releases, bestsellers and many other books for a standard price of $9.99 — which is less than it pays for them itself. Amazon takes a loss on the books, presumably in order to sell more Kindles, and also, most likely, to cement its dominance of the e-reader market. Publishers have long assumed that, once Amazon has the Kindle locked in as the default e-reader and has accustomed buyers to that $10 price point, the company could compel publishers to lower their wholesale prices on e-books.

What’s changed is that Apple has agreed to sell e-books through its forthcoming iBooks store according to what’s known as an “agency model,” much like selling on commission. Publishers will get to set the price of books — from $5.99 to $14.99, with new “hardcover” releases ranging from $12.99 to $14.99 — and the retailer will take 30 percent. Under this arrangement, as John Sargent, CEO of Macmillan, pointed out in a statement, the retailer stands to make more money off the sale of an e-book than Amazon is making now, and the publisher makes less. Book publishers are willing to accept — no, advocate for — this for a couple of reasons: They want more control over the value of their product and the prospect of an Amazon lock on the e-book market makes them very, very nervous.

However, Amazon refused to consider switching to such an arrangement. Macmillan retorted that in that case it would jolly well subject its e-books to “extensive and deep windowing.” This means that the e-book versions of new titles would be released months after the hardcover, as was the case with Sarah Palin’s memoir and Stephen King’s “Under the Dome” last fall. Whereupon Amazon pulled all Macmillan titles from its store, print included, thereby dragging even those customers with no interest in e-books into the fray

Watching this news wend its way through various niches of the Internet has been fascinating in its own right. If you happen to keep up with Web sites and Twitter feeds affiliated with authors and publishers, you’ll mostly see cheering for Macmillan and Sargent. He maintains that he is defending the “long-term viability and stability of the digital book market,” which is in danger of seeing the value of its products gutted as a loss leader to sell gadgets. Discussions in geek-oriented Web sites accuse Macmillan of bully-boy price fixing.

How to make sense of this? Here are a few things, not all of them widely understood, to consider:

You’re not really paying for an object. Most consumers believe that e-books should be a lot cheaper than print books because the publisher has been spared the expense of paper, printing, binding and shipping/distribution. However, only about 20 percent of the cover price of a new hardcover goes to those costs: about $5 out of $25. Retailers take from 40 to 50 percent, and after that, the majority of the cost of a new book goes to author royalties, editing, design, marketing, publicity, overhead and so on. But these elements aren’t material or tangible, and as a result, consumers seem to be skeptical about their true worth. Or, more to the point, their value now seems to be unstable. By comparison, when iTunes was first introduced a decade ago, hardly anyone believed that most of what they paid for when buying a CD went toward manufacturing the little silver disk and its plastic case.

Nobody knows how many Kindles are out there. Or, rather, only Amazon knows. The closest it’s come to revealing actual sales figures is a remark Jeff Bezos recently made about “millions” of Kindle users. Steve Jobs once said that the market for dedicated e-readers (devices used solely for reading) was too small to interest Apple. The fact that Amazon punished Macmillan by squeezing sales of print books as well as e-books suggests that cutting off the publisher’s e-book sales alone couldn’t cause sufficient pain.

IPads could well convert large numbers of people to e-books. Most of the tablets will be sold to people who plan to use them for watching video, browsing the Web, listening to music and checking e-mail — not for reading books. But once they’ve got the thing, the barrier to checking out the e-book feature is relatively low. I bought my iPod, for example, to listen to music and podcasts, and only later discovered the audiobook-download retailer, Audible. Today, audiobooks are the main thing I buy for my iPod, and I’d never paid much attention to them before that. To read a Kindle edition of a book, on the other hand, you’d have to be an e-book convert already — enthusiastic enough to fork over $250 for a Kindle right out of the gate. And you’ll have to buy a lot of $10 e-books to make up the cost of the device in savings off hardcover prices.

Actually, you can read Kindle books on other devices. True. I’ve read them on my iPhone. But how long will Amazon be willing to subsidize my smart-phone reading if it knows it can’t sell enough Kindles to pay for the loss it’s taking on $10 e-books? While Amazon claims to be motivated purely by a desire to provide consumers with low prices, its altruism will probably not extend past that point.

Not all Kindle books cost $9.99. A paperless copy of “Developments in Structural Engineering” by B.H.V. Topping will set you back a cool $496. Other titles cost pennies or nothing at all because they’re in the public domain or because their publishers hope that a (temporary) giveaway will ignite word-of-mouth recommendations or stimulate sales of books by the same author. Other Kindle editions cost about the same as the print version, and I’ve even heard of some (unsubstantiated) sightings of Kindle editions that cost more.

Reports of the Macmillan/Amazon clash prompted a lot of tirades along the lines of “most books aren’t even worth $10,” but this assertion is fairly meaningless. The Topping book costs 50 times more than the Kindle edition of “Wolf Hall” (if you could still buy the Kindle edition of “Wolf Hall), but I wouldn’t pay $1 for it, while I’d probably pay more than $10 for “Wolf Hall.” Yet some people somewhere are willing to pay 500 bucks for “Developments in Structural Engineering,” even if I doubt they’re glad to do it.

If the only new books you’ve ever bought are $7.99 mass market paperbacks, then any e-book priced higher than that will naturally seem exorbitant to you. But in that case, you probably wouldn’t be in the market for a hardcover (or a trade paperback) of “Wolf Hall” or “Game Change,” either. If you don’t especially want a particular book to begin with (and for each individual, this is the case with the vast majority of books), of course it’s not going to be worth $10 to you. The current tussle is largely over new, high-profile releases that some people are willing to pay more to read right away.

A person can only read so many books. Ask most people why they don’t read more and they’ll say it’s because they don’t have enough time, not because books cost too much. (Which isn’t to say they don’t wish books were cheaper, it’s just not the deciding factor.) Yes, you know this already, but it’s worth remembering when observers insist that lower book prices will lead to increased sales. Because, indeed, they will; many of the best-selling titles in the Kindle store are free. The publishers of “Developments in Structural Engineering” would probably sell more copies, too, if they only lowered the price to $1. However, I still wouldn’t buy it at that price, and the apparently spectacular costs of producing it are unlikely to be recouped by whatever modest sales increase is triggered by a whopping $495 discount. Few books have a broad enough appeal to be subject to mass-market economics, and so each title has to strike its own balance between cost and price, which is one reason why publishers want to regain their control over prices.

Price may not matter as much as convenience. If I’d convinced myself to spend $250 on a Kindle with the argument that I’d never have to pay more than $10 for a book to read on it, I’d be angry, too — just like the Kindle owners who complain on Amazon pages whenever titles exceed $9.99. But was saving money on individual books really the main reason they bought the device in the first place? Or was it the ease of getting the books you want right away and being able to carry dozens of them around with you in a lightweight package? If you want to read for free, you can go to the trouble of visiting the library. If you don’t mind waiting, you can pick up a used copy of any book for a song. If you’re not particular about which books you read — does anyone fall into this category? — you can download so many free, self-published titles from Amazon’s Kindle store to read on your home computer that you never, ever have to pay for another book again. But if you want exactly what you want when you want it, with minimal effort on your part, you often have to pay a bit more.

Ultimately, if the iPad takes off, the Kindle is in serious trouble. In order to maintain the complete, current selection of titles that is one of its device’s great features, Amazon has to be willing to come to terms with publishers. Publishers, eyeing the prospect of millions of new iPad owners — people who’d never have bought a Kindle, but are game to try out iBooks — now feel more free to threaten to restrict Amazon’s supply of e-books if their terms aren’t met. If the iPad offers all (or nearly all) of the convenience of the Kindle, plus color (imagine the graphic novels!) on top of the ability to watch videos, surf the Web and check e-mail, many potential Kindle buyers will be happy to fork over the extra cash for an iPad instead. (If they’re penny pinchers they probably wouldn’t be thinking of buying a Kindle in the first place.) And without the potential profits from sales of Kindle e-readers to subsidize it, that standard $9.99 price tag is unlikely to last long. Without it, how much is the Kindle itself really worth?