Perhaps the most illuminating anecdote recorded in Karen Abbott’s “American Rose: A Nation Laid Bare: The Life and Times of Gypsy Rose Lee” concerns the conception of the famous striptease artist’s son, Erik. Gypsy, at the age of 33, decided that she wanted to have a child — also, that she’d stick to the plan she’d once outlined to her sister June, of selecting as the father “the toughest, meanest son of a bitch that I can find, somebody who’s ruthless, and my child will rule the world.”

She chose the great Hollywood film director Otto Preminger and slept with him exactly once before leaving town without saying good-bye. Months later, on a visit to New York City, Preminger looked up Gypsy to find out what happened, and discovered her in the hospital, about to give birth to his son. “I want to bring him up to be my son only,” she informed the startled man, and made him promise never to reveal his own role in the matter. When Erik, at the age of 18, demanded to know why she wouldn’t tell him who his father was, she replied, “Because it’s none of your business.”

As portrayed in Abbott’s sad, smart, brassy biography, Gypsy Rose Lee was a creature of such overdeveloped boundaries because she was raised by a woman who had no boundaries at all. Gypsy’s autobiography, and especially the hit stage musical and film based on it, made the mother even more notorious than the daughter. “Gypsy!” was a horror story masquerading as a show-biz saga, and Rose Hovick was its monster. However, the play and the memoir were, like everything else having to do with that family, highly fictionalized: It turns out that Rose, the archetypal stage mother, was even worse in real life. She was, for example, guilty of at least two murders, and (according to Abbott) possibly a third.

Still, the bones of “Gypsy!” are essentially true: Rose’s voracious, almost inhuman ambition, the early fame of Gypsy’s younger sister (who could toe-dance at the age of two and a half) as “Baby June” on the vaudeville circuit and the desperation that set in when radio, movies and the Depression drove vaudeville to extinction. Then June ran away with one of the act’s chorus boys and things got even worse. Louise (as Gypsy was then known) could not sing, dance or act, but she was willing to take her clothes off on stage to put food in their mouths, and shrewd theater operators soon recognized that the way she did it was something special.

The most important of these men was Billy Minsky, of the famous Minsky Brothers, the kings of New York City burlesque, whose music halls were patronized by gangsters, bohemians, socialites, journalists — even the city’s sharp-dressing mayor, Jimmy Walker. The rise (and fall) of burlesque is one of three narratives Abbott follows, in alternating chapters, throughout “American Rose.” It’s a wild tale of the Roaring ’20s, full of outrageous stunts and breathless gambits devised to woo audiences, dodge censors and outfox competitors; in fact, the brothers themselves inspired a musical, “The Night They Raided Minsky’s.” Before the opening of one theater, Billy Minsky sent suggestive, perfumed letters to every business owner in the neighborhood, supposedly a come-on from Mademoiselle Fifi, the star performer he’d imported from France (she was in truth the daughter of a Quaker policeman from Pennsylvania). Crowds lined up around the block.

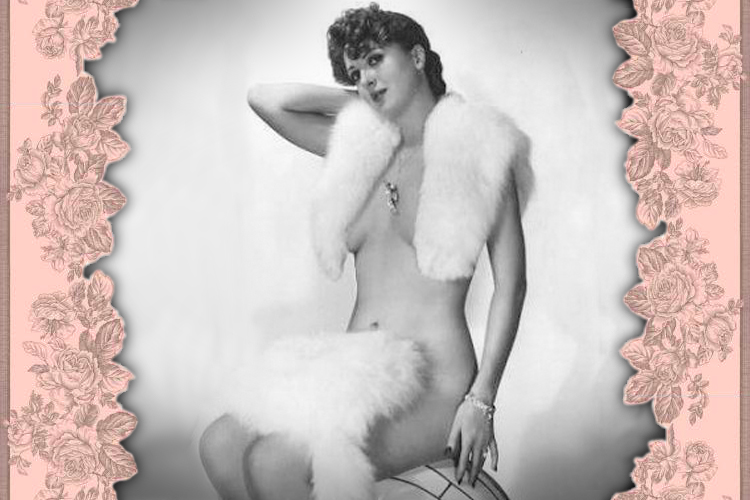

Billy spotted Gypsy in a Newark burlesque house in the early ’30s, told her to stop curling her hair, brought her to New York and made her a star — but the essence of her act was already in place. She was funny, smart and behaved like a sophisticated lady, who, much to her own surprise, happened to wind up half naked in front of a crowd of appreciative men. In later years, she referred to her performances as “straight comedy,” rather than “an exotic sexual spectacle,” but it was really a combination of the two; poised humor as an aphrodisiac so potent that, according to one eyewitness, “every slight smile, curved hip, raised arm and seductive thrust created a frenzy.” She always had a quip for the press (“I wasn’t naked,” she said after one raid. “I was completely covered in a blue spotlight”) and her own talent for publicity soon made her a household name. The more famous and adored she became, the fewer garments she had to take off.

No one really knew Gypsy Rose Lee, as one source after another informs Abbott. Even her sister, who became a noted actress under the name June Havoc and who granted Abbott an interview shortly before she died in 2010, wrote Gypsy a letter complaining “you don’t let me very close.” Both women were excruciatingly but inescapably fused to their mother, and this triangle defined their lives. Gypsy married three times, although not to the only man who seems to have really gotten under her skin — the impresario Mike Todd, who died in a plane crash one year after marrying Elizabeth Taylor. Gypsy and June fought, then reconciled, with June helping to nurse Gypsy through her final battle with lung cancer in 1970. Even so, as Gypsy lay dying, she whispered to Erik, “After I go, don’t let June in the house. She’ll rob you blind.”

The impenetrability of her subject doesn’t slow Abbott down much, but the sheer preponderance of ass-covering, self-mythologizing sources sometimes sets the reader’s head to spinning. Was the raid on Minsky’s a real raid, or not? What exactly happened to Gypsy and Rose during the year they “never talked about,” between the day Gypsy started stripping and the day Billy Minsky singled her out for stardom? Was Gypsy at her upstate New York farmhouse on the night in 1937 when a young woman — part of a “lesbian harem” that congregated around Rose — supposedly (but not very plausibly) shot herself in the head with a rifle? In the end, you have to surrender any attachment to the facts, and stand in awe of the titanic will that went into the creation of Gypsy Rose Lee. She was a “strutting, bawdy, erudite conundrum” (to quote Abbott), a survival artist of the highest order whose masterpiece consisted of figuring out how to “mine her past so she’d never have to relive it.”