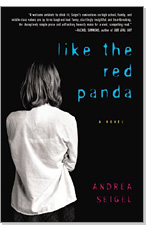

I have to come clean. I didn’t want to like Andrea Seigel’s “Like the Red Panda.” In fact, I started reading the book hoping I would hate it.

Does the world really need another treatise on teen angst? Another attempt to capture the suburban despair and disillusionment of our nation’s most overprivileged generation? (One not that far removed from my own.) These days, real life is filled with enough of our own self-absorbed, self-entitled bellyaching. Do we really have to read about it in fiction as well?

After finishing “Like the Red Panda,” and finding myself steadily sucked into the world of teenage protagonist and narrator Stella Parish, I’ve come to this conclusion: Yes, we do — sometimes. This happens to be one of those times.

Seigel’s humorous sense of the tribulations of high school — phony friends, bad-boy boyfriends, parents who just don’t understand — makes this an entertaining read, but many lesser books and films cover the same turf. “Like the Red Panda” succeeds because it transcends cliché. Seigel’s book is not teensploitation trash or a literary version of “Beverly Hills 90210.” If you read this expecting twisting soap-opera story lines, you’ll probably be disappointed.

Granted, Stella’s life is not entirely typical. She was adopted at the age of 11 by an emotionally distant couple, after her yuppie parents died at the same time of a drug overdose. Her only remaining family is a selfish, cynical grandfather who lives in an old-folks home — and whom she visits on weekends only because it gives her an excuse to miss synagogue with her adoptive parents, the Roths.

Now an academic overachiever on the verge of graduating and going to Princeton, Stella decides that the trappings of life — getting good grades, hollow interactions with friends and family, and a future that promises more of the same — hold no meaning for her anymore, so she begins to plan her suicide.

But the plot doesn’t drive this story as much as the simple power and honesty of Stella’s voice, rendered by Seigel with amazing precision, subtlety and a perfect current of self-deprecating understatement. Considering that Seigel is barely out of high school herself (well, OK, she’s 24), maybe that’s not so surprising. And similar voices — from Holden Caulfield to MTV’s Daria — dot our cultural landscape like SUVs in a strip-mall parking lot. In that sense, there’s nothing particularly unusual about Stella.

What Seigel does particularly well, however, is to make her character complex and three-dimensional enough to resist easy stereotyping. Stella is not just a walking cartoon, bitter and jaded, angry at the world for no good reason. At heart, she’s an idealist, someone who still cares very deeply for the people in her life, even those who’ve treated her badly. Like a recovering Catholic, she wants to believe there’s a purpose for everything, an underlying goodness that drives life; she’s just seen too much — too much loneliness, too much emptiness, too much pain — to allow her to have faith in something she instinctively knows does not exist.

This subtle interplay between hope and despair lends Stella a universality that’s appealing and likable, comfortable and familiar, capturing in the quirks of her personality all the contradictions that make the high school years both so overwhelming and so memorable. She has a fantastic eye for the kind of ridiculous hypocrisy that seems especially prevalent at the adolescent phase, when one first begins to rectify the dreams of youth with the realities of being an adult. But her selflessness and purity of intention allow us to care deeply about Stella, where other disillusioned types might come across merely as selfish and annoying.

Our care for Stella gives her ultimate intention — to kill herself after her graduation — that much more resonance. We admire her conviction and her resoluteness, but we cannot bear the thought of such a vibrant individual dying. And that’s exactly why “Like the Red Panda” rises above the triviality of a typical teen-angst anthem: By artfully evoking the despair, even the hopelessness, of such an endearing character, Seigel reaffirms our own private hope that maybe, after all, life does have meaning.

Our next pick: Drugs, aliens, random sex, a Cape Cod vacation and, strangest of all, a feckless middle-aged protagonist who won’t annoy you!