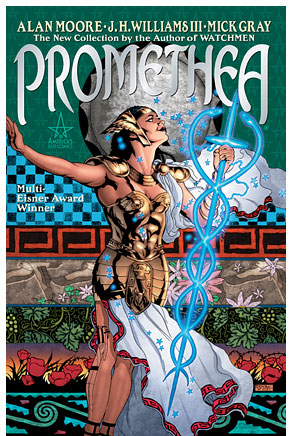

When “Promethea” began its 32-issue comic-book run in 1999, it looked like it was going to be British writer Alan Moore’s riff on Wonder Woman: a story about a superheroine with mythological connections, one of the flagship titles of Moore’s whimsical America’s Best Comics project. By the time it ended a few months ago (the final sequence is collected in “Promethea Book 5,” to be published in a couple of weeks by ABC), it had turned into something very different: a rather wonderful excuse for the 51-year-old Moore to explain his version of hermetic Kabbalistic philosophy.

Moore’s got a reputation for writing remarkable, formally structured mainstream comic books, including a few that are permanently lodged on the graphic-novel bestseller lists. Most of them are so engaging that Hollywood types thought it’d be a great idea to adapt them into movies, and so complicated and subtle that they’ve turned out to be unfilmable (like “Watchmen,” which Hollywood’s been batting around for over a decade), or the resulting films turned out to be travesties (like “The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen” and “From Hell”; this doesn’t bode well for the forthcoming “V for Vendetta” movie). In the last decade or so, he’s also gotten very heavily into magic of the robes-and-grimoires sort, and has talked about his close relationship with the second century snake-deity Glycon. “The idea of the god is the god,” he’s said. That’s the thesis behind “Promethea,” which he’s described as “a magical rant seemingly disguised as a superheroine comic.”

But Moore doesn’t draw the comics he writes; his artistic collaborators on “Promethea” were J.H. Williams III and Mick Gray. They developed a lavish, eccentric visual style for the series, in which almost every two-page spread is unified by decorative design elements and symmetries. Williams is something of a chameleon — his covers to the individual “Promethea” comics alluded to Alphonse Mucha, Peter Max, Winsor McCay and whoever else seemed appropriate.

In the first “Promethea” book, though, Williams and Gray’s art is mostly a graceful variation on the standard superhero-comics mode, and so is the story. College student Sophie Bangs lives in an alternate-world, modern-day New York City that’s full of flying cars, futuristic technology and “science-heroes.” As the series begins, she discovers that she’s the latest incarnation of Promethea, a mythical heroine born in fifth century Egypt whose physical presence can be invoked by acts of imagination and creativity. (Sophie becomes Promethea by writing poems about her.)

Through Book 1 and the first half of Book 2, “Promethea” is Moore at his most playful, having fun with his setup and setting. Sophie’s foil is her snarky best friend Stacia, whose favorite pop-culture icon is a lovely, daffy running gag: something called Weeping Gorilla, who appears on omnipresent billboards sobbing into his fur and thinking bummed-out thoughts (“We probably expect too much from George Lucas…”). The high-tech sensory overload of “Promethea’s” New York is packed with delicious details that Moore never bothers to explain — it’s only natural that the city’s mayor has multiple personalities, even before he’s possessed by demons. (Newscast chatter: “Speaking yesterday, the Mayor said ‘I am Legion. All shall kiss my smoldering hoof.'”) And the chaos in the street scenes frames the series’ contrast between the material and spiritual worlds nicely.

Midway through Book 2, things start getting weird. Sophie meets a grubby, creepy old magician, Jack Faust, who says he’ll teach her about magic in exchange for sex with Promethea — and she takes him up on his offer. An entire chapter (an issue of the original comic) is devoted to a tantric sex scene, complete with extensive discussion of the magical significance of clothing and sexuality. At the beginning, it’s impossibly squalid — the idea of the gorgeous heroine in bed with a potbellied, warty lech is meant to make the reader squirm hard. (“Who remaindered the book of love?” thinks Weeping Gorilla on the sign outside Faust’s filthy apartment.) But the chapter’s tone gradually turns grand and psychedelic (if not exactly erotic), then oddly tender, and it lays the foundation for the rest of “Promethea”: the idea that there’s magical symbolism in everything, no matter how debased.

The second book concludes with a flabbergasting visual and verbal juggling act: a chapter called “Metaphore,” in which the twin snakes on the caduceus Promethea carries explain the history of humanity to her, in rhyming couplets, by way of the sequence of major-arcana Tarot cards. The snakes are named Mike and Mack, as in “micro” and “macro”; they can’t keep straight which one is which. (As above, so below, as the saying goes.) Their Tarot isn’t quite the traditional version: Every card from the common Rider-Waite-Smith deck is redrawn as a cute little cartoon, and “Judgement,” for instance, is replaced by Aleister Crowley’s suggestion “The Aeon,” its angel replaced on the card by Harpo Marx (symbolizing Harpocrates, the Greek god of silence), honking rather than blowing his horn (“ankh ankh” — oh, yes, he’s wearing clothes decorated with ankhs, rather than the angel’s cross).

Every page of “Metaphore” is crammed full of symbols and details. Each page includes a set of Scrabble tiles spelling out a relevant anagram of “Promethea” (“Ape Mother,” “Me Atop Her,” etc., with the tiles “scored,” as in Scrabble, with a corresponding letter of the Hebrew alphabet), plus backgrounds depicting icons of human culture from that stage of history, plus a painted image of Crowley (aging over the course of the chapter from a fetus to a corpse, and telling a joke that’s a metaphor for how magic works), plus a tiny little devil or angel (on the left- and right-hand pages, respectively), plus decorative “go-go checks” that allude to ’60s comic books. It’s amazing Williams and Gray’s hands didn’t fall off by the time they finished drawing it.

Apparently emboldened by the fact that his collaborators hadn’t run away screaming, Moore threw the plot out the window for most of Books 3 and 4, and devoted them to an extended explanation of the Kabbala’s Tree of Life, the map connecting the sephirot or spheres representing God’s attributes (or states of mind) in the Jewish mystical tradition. (The links Moore suggests between the Kabbala and the Tarot are that the 22 major arcana correspond to the 22 paths between sephirot on the Tree of Life, and that, more important, both systems are useful as allegorical representations of the range of human experience.) The conceit of “Promethea’s” middle act is that Sophie and her spirit guide, the previous incarnation of Promethea, spend a chapter apiece traveling through metaphorical representations of each of the 10 Kabbalistic sephirot (plus an extra “invisible sphere” Moore sneaks in between the third and fourth).

There’s a lot of ungainly expository dialogue in those two books (“This is the fourth sphere, right? ‘Chesed,’ there on the arch above the Jupiter symbol. I think it means mercy”). Their ratio of profundity to claptrap varies with the reader’s openness to semi-digested Crowley, and occasionally Moore threatens to sprain an eyelid from winking so hard. (Sophie meets Hermes, who tells her that gods, as “abstract essences,” can only be perceived through linguistic constructs like “picture-stories.” Picture-stories? she asks. “Oh, you know. Hieroglyphics. Vase paintings. Whatever did you think I meant?”) Some readers complained at the time these installments first appeared that they felt like Moore was lecturing at them, and that’s absolutely true. But complaining about “Promethea’s” transformation from a graphic novel to a graphic textbook is missing the point: The idea of it isn’t to tell a story so much as to present a gigantic mass of arcane philosophy as entertainingly and memorably as possible.

In fact, the Kabbala volumes of “Promethea” are thrilling, partly because they’re total eye candy. Williams and Gray draw each chapter in a style of its own, with a color palette dominated by the part of the spectrum associated with that chapter’s sphere. The panel backgrounds for the “Chesed” sphere are painted with blotchy, van Gogh-inspired brush strokes, suffused with blue; Binah, the realm of the whore Babalon, is drenched in blacks and dark, tinted grays, with outlines that crinkle like woodcut prints. The colors of the highest sphere, Kether, are traditionally white and gold, and its chapter is illustrated almost entirely in shimmering, pointillist golden yellow. When the story gets back to earth a few pages later, it’s hard to readjust, although Williams keeps up the delirious compositional tricks from the Kabbala section.

That leaves Book 5, set a few years later, in which some leftover bits of good-guys-vs.-bad-guys plot from the early stages of the series get mopped up, and Sophie becomes Promethea one last time in order to end the world. (“End,” not “destroy.” “The world is our systems, our politics, our economies … our ideas of the world!,” an earlier Promethea explains to her; the apocalypse she brings on is more like an enlightenment.) This is at least the fourth time Moore has ended a major series with a vision of global utopia, or at least some kind of benign revolution, although to be fair it’s not exactly a cop-out in “Promethea,” given that its protagonist is named after the god who brought light to the world.

As entertaining as it is, most of Book 5 is an exercise in clearing the decks for the final chapter, and by then it’s clear that hardcore formalist Moore has arranged the series into 32 chapters for a reason. The final one is 32 pages long, each page corresponding to one of the tarot’s 22 major arcana or one of the 10 spheres of the Kabbala. (They can be read in the order printed in the book, or they can be assembled into two four-page-by-four-page arrays — which form gigantic images of Promethea’s face — and read in that order instead.)

This time, it really is a lecture, consisting of a nude Promethea fluttering around candy-colored background abstractions and limning Moore’s cosmology, which centers on snakes, psychedelic mushrooms, sensory overload, and language and art as consciousness-altering tools — especially in comic book form. There is no pretense of narrative, just a circular monologue (“As readers, you are physical beings engaging in a DNA snake-dance with me, a fiction, your immaterial, lunar imagination”), abetted by captions that invoke mythology, literature, science and a little too much pseudoscience (“The butterfly’s random fluttering from one point to another also accurately models how thought follows a fractal path from concept to concept”).

Without the rest of the “Promethea” series to explain its vocabulary and mystical-theoretical grounding, it would make no sense at all, and even in the context of the story that’s led up to it, it’s rough going. As a philosophy of life, it’s questionable at best; it’s a huge pill, and it’d be unswallowable without the smooth sugar coating of Williams’ artwork. As an aesthetic philosophy, though, it’s astonishingly fertile, recasting the mind as the “radiant heavenly city” Moore promises, populated by the gods that live in the human imagination, and laid out according to the road maps he’s presented in the guise of a grand adventure story. He may be the only person who lives there right now, but at least he’s inviting the rest of us.

Douglas Wolk’s writing on comics and graphic novels appears the first Friday of each month in Salon Books.