One moment in the film life of Dirk Bogarde is particularly clear proof of his superiority over other leading men of the time: Bogarde and Ryan O’Neal, during one of the last scenes of “A Bridge Too Far,” are both staring out at the scene of their lost battle. Bogarde’s eyes clearly convey his great shame, his processing of a great human loss and vast failure. Through O’Neal’s eyes, one can see his brain trying to look worried.

It’s a damning lesson in the difference between good acting and bad acting; a good actor makes the entire audience psychic; the glimpse of a naked emotion can be hair-raising. Bad actors make you aware of their laborious acting process: They yank you from the moment and drag you into a slide show of their personal inhibitions. “Come on, Ryan, a-a-a-act,” one is compelled to yell at the screen in a tortured thespian voice. (Not that O’Neal, the Matt Damon of the ’70s, is my personal whipping-celebrity. He is, however, like many other leading pretty boys, exemplary of Hollywood’s failure to fully grasp the idea that real acting requires subtle emotional gifts.)

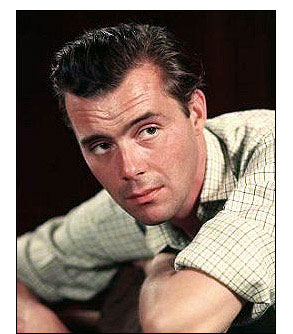

After a stint as an officer in the British army’s Air Photographic Intelligence during World War II, Bogarde, who was born Derek Van den Bogaerde in London in 1921 (his father, an editor at the Times of London, was Flemish), joined a theater group. He was noticed quickly and given small parts in several mystery films, then broke through as a celebrity in the worthless medical comedy “A Doctor in the House,” wherein he played a nervous medical student. While comedy isn’t Bogarde’s strong suit — he has no ironic distance from his work and is hence incapable of buffoonery — the “Doctor” films, of which he did three, were nonetheless a demonstration of the way he could single-handedly dignify a film by bringing his own unflappable truth to it. By the 1950s, Bogarde had been singled out by British cinema bosses as a star. He became a matinee heartthrob; one critic has aptly described him as the “Leonardo DiCaprio of his day.”

“I simply hated being a Film Star,” Bogarde wrote in one of his autobiographies, “A Particular Friendship.” “For about 10 years I was never able to be free … I had my flies ripped so often that eventually, in public, I had to have a side zip … can you imagine anything more humiliating than that? Anyway, apart from all that, I have an absolute horror of being ‘looked at.’ An eye phobia or something. So I’m in quite the wrong profession obviously.”

Today, it is likely that anybody in the U.S. who is familiar with Bogarde thinks of him as the quintessential Gentleman’s Pervert. This role is extinct now; intelligent perversion is totally missing from today’s cinema. If there is perversion, there is no subtlety. Bogarde, in his key roles, represented an intellectual decadence that nobody making films today is smart or bold enough to touch. In today’s corporate entertainment climate, there have been no book burnings, per se, but the self-censorship that most media venues impose on themselves in the pursuit of mainstream money nearly produces the same cultural effect that the Nazis would have if they had won the war and succeeded in getting rid of all the “decadent” art.

Whereas American actors have a penchant for scenery-chewing obviousness and two-dimensional fangs when they play a morally remiss character, Bogarde always brought a human face to corruption; he sympathized strongly with characters whose questionable actions were the result of their enslavement to power, sex or, most maddeningly, bureaucracy.

By the ’60s, Bogarde had had enough of being screamed at by adoring girls, and he began exercising a strong discrimination about the roles he took — at his point, Bogarde seems to have selected films on the basis that they actually said something. He flouted taboos by making “Victim” in 1961, in which he played a public figure being blackmailed for homosexuality.

(Bogarde himself was gay but denied it during most of his career; though he wrote of his early sexual relationships with women and his passionate love for Judy Garland, he never wrote about the love of his life, his manager and partner Anthony Forwood, whom he was with for more than 50 years.)

If Bogarde’s choice of roles is any indication of how he felt about the society in which he lived, it is clear that he had a deep disdain for the hubris of upper-class twits, but this conviction never overrode his compassion toward man’s frailty. He always found a way to make his characters compelling and almost sympathetic, no matter how vile they were. Bogarde burned brightest in roles with huge dramatic arcs — he clearly loved ascending and descending from one side of a paradox to the other, particularly from power to slavery or vice versa.

His hunt for a great collaborator led him, in 1963, to a fortunate pairing with director Joseph Losey, with whom he would make several films, the first and best of which was “The Servant.” Bogarde plays the Machiavellian butler to snot-nosed, upper-class James Fox with a distinctly sadomasochistic flair. As Barrett, the ultimate Jeeves gone wrong in Harold Pinter’s brilliant, structurally flawless script, Bogarde effortlessly evolves from genteel supplication to pitiless cruelty.

Fox is in his finest form as the weak-minded aristocrat whom Barrett exploits. Bogarde’s face is a study in reptilian cool: He can eat revenge cold; he is insouciant and unfazed during the most brutal personal confrontations — he lets the audience do the cringing for him.

This film offers a first glimpse of Bogarde’s famous eyebrow-cocked, bedroom-eyed stare, which he levels on Sarah Miles. It is the most blazingly sexual look I have ever seen on an actor’s face — a look that doesn’t stop at suggesting only the bedroom, when devouring his on-screen love interest, but goes on to suggest the kitchen table, the floor, a public elevator and a basement dungeon of his own sinister design.

“The Servant” is one of several Bogarde vehicles that feature a strange psychological mind-fuck “game” of the type only seen in films from the ’60s involving shallow beautiful people abusing each other at drunken parties. It is an interesting Albee-esque device: the freedom of intoxicated expression that was post-’50s pill-popping Freudian alcoholism, but pre-’60s pothead love ‘n’ innocence.

The pleasure that Barrett the butler takes in his cruelty is most evident in a round of hide-and-seek with his dissipating master: “You’ve got a guilty se-cret,” Dirk chants in a singsong voice as Fox trembles and sweats in terror, cowering in his hiding place. “I’m getting warmer … You’ll be caught!”

Another key early role for Bogarde was in John Schlesinger’s “Darling” (1965) — another film expressing a vast revulsion for the self-indulgent high jinks of high society, where drunken millionaires in mod outfits brutally mind-fuck each other in the name of fun. Bogarde plays a sensitive, married TV interviewer who falls for up-and-coming model/actress/opportunist Julie Christie, the ultimate hot party girl.

Her jet-set world is full of upper-class buggerers, gamblers and philanderers; she trips along for the ride while Dirk watches, suffering. When Christie aborts their pregnancy, Bogarde, in a masterfully subtle moment, enters her hospital room with flowers. The way he holds them, sideways, says everything. A happy man, with any hope, holds flowers straight up.

It is an interesting film for a number of reasons — the opening shot features a billboard of Julie Christie, “The Ideal Woman,” being plastered over the faces of starving Biafran children. Bogarde gets to display his customary eight-octave emotional range and to utter lines like, “You’re a whore, baby, that’s all, and I don’t take whores in taxis.”

The critical acclaim Bogarde earned at this point in his career secured his position as one of Britain’s best actors.

A less successful Losey/Pinter/Bogarde effort was “Accident” (1966), in which Bogarde plays a middle-aged university tutor who gets tangled in an affair between two of his glamorous pupils (one of whom is played by the impossibly beautiful young Michael York) when his more successful friend and contemporary leaves his wife for the girl, whom Bogarde also loves.

The pacing seems to be suffering from the constipation of middle age, which I believe is Pinter’s fault; the script is a turgid exploration of impotence and emasculation. While it is an interesting meditation on the kinds of comparisons men make with each other that drive them crazy at a certain age, the restless dissatisfaction of a midlife crisis is so well put across by Bogarde that watching the film is as dreadful as being mired in that particularly morose, self-indulgent frame of mind.

In “The Fixer” (1968), Bogarde uncharacteristically plays a kindly role, and while he brings his usual effete, eyebrow-cocking sensitivity to it, there is something a little unctuous about the portrayal. In allowing his naturally compassionate instincts to rule his performance, Bogarde comes off as almost too garishly sainted. His eyes appear to be moistened by the beauty of his own moral rectitude. His lines are part of the problem, but this role is an argument for Bogarde’s being best used as an agent of corruption.

Bogarde’s collaborations with Luchino Visconti were also particularly fruitful. “The Damned” (1968) is a vintage Bogarde vehicle, in which he plays the overreaching lover of the heiress to the Essenbeck steel works, a German company under pressure from Hitler’s National Socialist Party, which is quickly gaining political speed.

In the interest of preserving the corporation, the family opts to cooperate, albeit unhappily, with what becomes the Nazi regime. “The Damned” is a great film: moody, gorgeous, smart, brutal and sleazy. Helmut Berger is superlative as the perverse son of Bogarde’s lover; Charlotte Rampling, at her most absurdly fetching, provides stellar eye-candy in a supporting role. Bogarde, as is customary for him, quietly anchors the near-melodramatic extremities of the plot with his own fearless honesty.

“Personal morals are dead. We are an elite society where everything is permissible,” one of the characters, quoting Hitler, tells Dirk, this concept being the axis on which the film’s characters eventually spin out of control.

Bogarde’s character, under pressure from his Lady Macbeth-esque lover, finds himself in a downward spiral of unending moral degradation. “I’ve accepted a ruthless logic, and I can never get away from it,” Bogarde gasps, as his corrupt decisions catch up with him. It’s a line no American star could deliver convincingly.

As professor Gustav von Aschenbach in Visconti’s “Death in Venice” (1971) Bogarde delivers one of his finest performances in his most demanding role. For the character of a great composer frightened by his failing health and the prospect of death, he abandoned any semblance of vanity, allowing himself to look clerkish and mealy; he adopted a gimpy, mincing little walk, his bald spot showing through a gray-streaked comb-over.

The film is studded with long-haired Thomas Mann-erisms that only an actor of Bogarde’s intelligence could pull off without sounding absurd: “Evil is a necessity — it is the food of genius” and “Beauty exists without regard to your labor.”

Meanwhile, in Venice, absurdly beautiful boys play homoerotic tackle games in thin one-piece bathing costumes. Youth and beauty mock von Aschenbach; the Polish boy he becomes obsessed with (who looks like a young Candice Bergen), gives him sultry come-hither stares that destroy him — he is tormented by a spirit willing itself toward ultimate beauty while encased in advancing decay.

There is an incredible moment of Bogarde’s screen magic during the famous scene at the barbershop. The barber darkens his hair, daubs strange white makeup onto his cheeks and rouge on his lips, in an effort to restore his youth. Von Aschenbach allows himself a tiny, approving, hopeful smile at his reflection in the mirror when his makeover is complete. It’s truly horrible, the smile of a man about to fly into a thousand bloody pieces, trying to hold himself together with lipstick.

His death scene is a particularly awesome feat of emotional athleticism: Dirk laughs, dies, cries and sweats black hair dye down his face while reaching a profound philosophical Truth, watching the beautiful boy walk out to sea. Bogarde’s longing is palpable; he plays the scene so deeply he manages to evoke nostalgia, physical surrender, awe, misery, futility, lust and a strange, vindicating dignity, all at the same time. (Try that, Kevin Costner.)

The jewel in the crown, in terms of American appreciation of Dirk Bogarde, at least by the decadence-loving cognoscenti, is Liliana Cavani’s remarkable “Night Porter,” wherein Bogarde plays an ex-Nazi “doctor” who had, in the war, been given to performing creatively lethal experiments on his charges at a concentration camp. Generally speaking, when an actor plays against his own sexual preference, there is something unconvincing — he can’t fully commit to it, in one way or another. You can’t see their eyes appreciating, let alone sexually worshipping, the physical subtleties of lovers that they wouldn’t choose in real life. Bogarde, however, so convincingly plays his delirious enslavement to the fragile Charlotte Rampling (as an ex-inmate of the same camp) it is difficult to believe that off camera he preferred men.

His love isn’t a healthy love, but it is electrified by the weakness he feels in it. Few other actors, if any, could so perfectly convey such a sincere, trembling obedience to helpless, fetishistic love with a stiff upper lip.

A Bogarde Web site includes the following excellent analysis of the film (quoted from an article whose source I’ve been unable to pin down): “Cavani … incorporates sexual psychology into a rhapsodic view of human obsession tending towards mysticism … the contract of love entered upon by Bogarde and Rampling — psychotic, born of weakness rather than strength — is a contract of death. It awaits only their reunion to be completed … But, in the very midst of depravity, there is ecstasy and tenderness and the selflessness that is also found in ‘normal’ love.” (In other words, it could never be a Julia Roberts vehicle.)

Toward the end of his life, Bogarde moved with Anthony Forwood to Provence, where he began to write well-received books. He was knighted in 1992 and suffered a stroke in 1996 that required that his final years be spent under 24-hour care. He was most vocal, toward the end of his life, on the issue of voluntary euthanasia, of which he became a staunch proponent after witnessing the protracted death of Forwood in 1988. He made particularly interesting remarks in an interview to John Hofsess, London executive director of the Voluntary Euthanasia Society:

“My views were formulated as a 24-year-old officer in Normandy … On one occasion the Jeep ahead hit a mine … Next thing I knew, there was this chap in the long grass beside me. A bloody bundle, shrapnel-ripped, legless, one arm only. The one arm reached out to me, white eyeballs wide, unseeing, in the bloody mask that had been a face. A gurgling voice said, ‘Help. Kill me.’ With shaking hands I reached for my small pouch to load my revolver … I had to look for my bullets — by which time somebody else had already taken care of him. I heard the shot. I still remember that gurgling sound. A voice pleading for death …

“During the war I saw more wounded men being ‘taken care of’ than I saw being rescued. Because sometimes you were too far from a dressing station, sometimes you couldn’t get them out. And they were pumping blood or whatever; they were in such a wreck, the only thing to do was to shoot them. And they were, so don’t think they weren’t. That hardens you: You get used to the fact that it can happen. And that it is the only sensible thing to do.”

Bogarde never shied away from speaking his mind. In his 1983 autobiography, “An Orderly Man,” he expressed his dismay about what had become of the film world:

“Now the cinema is controlled by vast firms like Xerox, Gulf & Western and many others who deal in anything from sanitary-ware to property development. These huge conglomerates, faceless, soulless, are concerned only with making a profit; never a work of art … It is pointless to be ‘superb’ in a commercial failure; and most of the films which I had deliberately chosen to make in the last few years were, by and large, just that. Or so I am always informed by the businessmen. The critics may have liked them extravagantly, but the distributors shy away from what they term ‘A Critic’s Film,’ for it often means that the public will stay away. Which, in the mass, they do: and if you don’t make money at the box-office you are not asked back to play again.”

It is a tragedy that our film world today produces no Bogardes, nor the heady, depraved scripts worthy of one. Hopefully, cinéastes will keep Bogarde’s better films in circulation, so that future generations can experience the sexual chill of those wet brown eyes and that one renegade eyebrow that mocks everything sacred while the rest of his face lies perfectly still.

Author’s note: Much of the biographical information for this article was pirated from the lovingly assembled Dirk Bogarde Homepage.