Cultural offerings from the '70s and early '80s that used to seem like schlock, when juxtaposed to the current, even schlockier schlock, don't seem so schlocky anymore. I recently heard "Borderline," the first Madonna hit, on the radio when I was in a video store, and it made me involuntarily dance. It didn't when it came out -- there were far funkier songs going around, and Madonna's music, though infectiously hooky, seemed sort of wannabe-funky and contrived. Now, in the wake of Diane Warren's genocidal takeover of the radio waves and the horrifying success of Poppin' Fresh thongsters like Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera, the old Madonna/Jellybean Benitez cuts sound newly organic and ingenious.

There are similar resurrections when one re-investigates the world of pop film from the '70s and '80s. John Hughes films that seemed sanitized at the time now look pretty edgy. And Robby Benson, critical whipping boy of the disco era, looks like a respectable actor, at least when compared with the some of the feckless young Hollywood jag-offs of today.

If a young man is a certain kind of teen idol, like David Cassidy, and teenage girls demand soft-focus posters of him oiled and shirtless with feathered hair, nobody will ever take his work seriously -- there is a third dimension, image-wise, that such personae aren't allowed in terms of public perception.

David Cassidy, looking back with new eyes, was actually a very talented teen idol -- and Robby Benson, the David Cassidy of dramatic acting, actually had compelling charm and a wide emotional spectrum, but he got trapped in a sugary pubescent simp rut that kneecapped any respect he might have gotten.

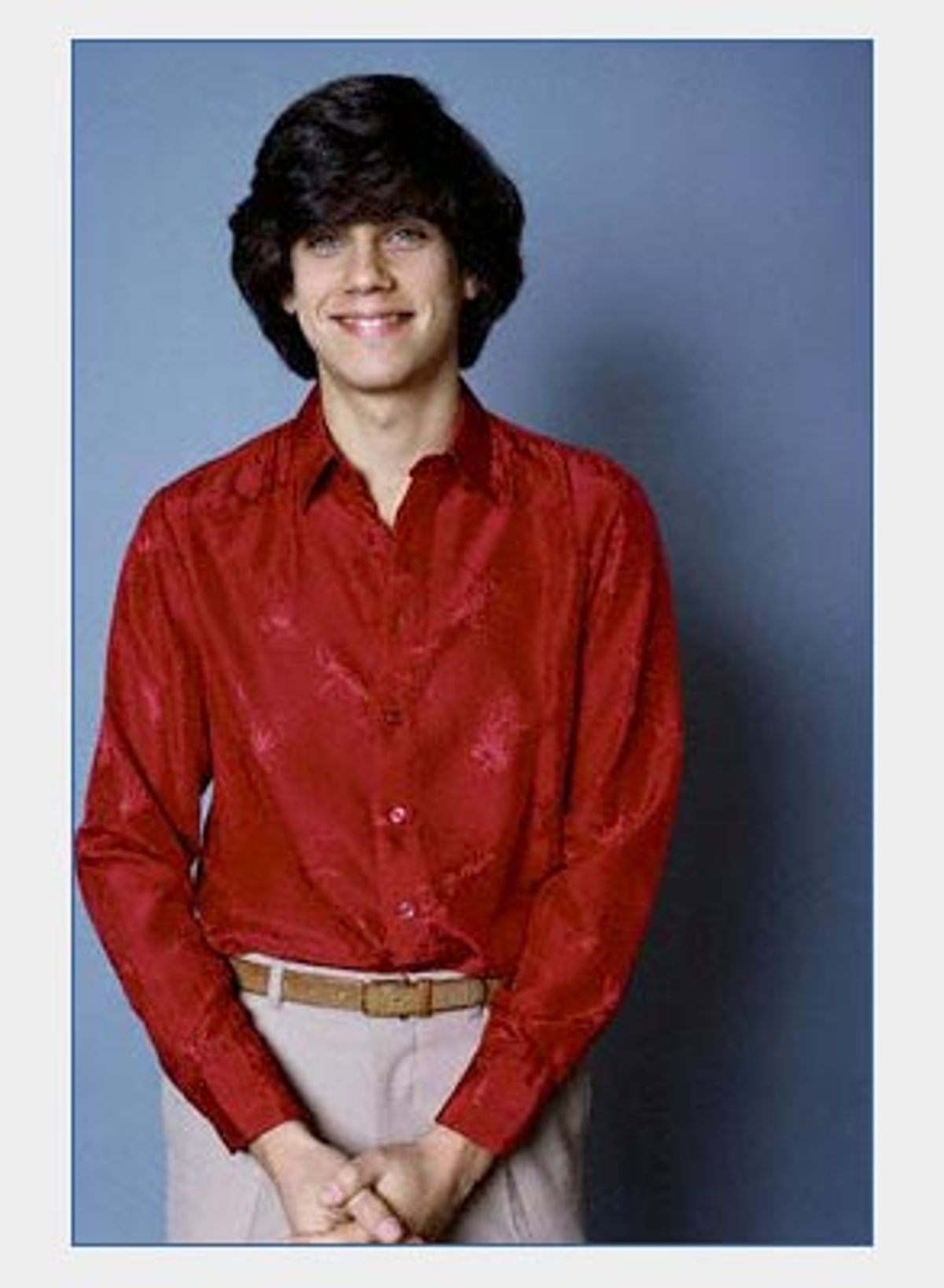

Robin David Segal, aka Robby Benson, was too pretty to be taken seriously, but he was unusual -- more "ethnic" than the average teen idol, also a bit more complex. He is always described as doe-eyed, but his eyes are more eerily religious, like backlit blue marbles. If Benson had been allowed (or had allowed himself) to develop a little more coolness and/or masculine, sexual alertness, his teary-eyed vulnerability would have had more legs. But since his supersensitivity was coupled with a cloying, chaste manner, he was written off as a dickless square. It didn't help that the roles in which he was cast were so unctuously sentimental.

Male critics hated him with a nearly irrational fervor, and the sharper female critics didn't have much use for him either -- grown-ups were put off by the flocculent way Robby carried himself. Compared to other leading young men of the time (e.g., the strutting peacock magnificence of John Travolta in "Saturday Night Fever"), Benson moved on tippytoes, like he was carrying a dying baby bunny in a potholder. Benson represented a soft, sexless flavor that called for a taste nobody but grade-school girls and men who were light in the loafers wanted to acquire.

Thumb critic Gene Siskel wrote in 1986 about the uncomfortable experience of running into Robby Benson during a film festival, setting it up by describing Benson as "one actor to whom I have regularly given the most negative reviews in my 17 years as film critic":

"Benson's manner and voice make me squirm as soon as I see him on-screen. He always seems to be saying with every performance, 'Please like me; I'm so helpless.' This is not appropriate behavior for a 30-year-old actor ... "

Siskel was not alone. Most critics of that era were giddy with a fashionable hatred of Robby Benson -- it was a mark of taste and sophistication. It may have been nearly impossible for Benson to get an unbiased review in such an atmosphere.

I first heard of Robby Benson as a very small child when "Ode to Billy Joe" came out in 1976 -- a film based on the Bobbie Gentry song. Robby was 20 at the time, but could have easily passed for 14.

Robby is Billy Joe MacAllister, who jumps off the Tallahatchie Bridge. "Don't seem like no good ever came to nobody on this bridge," one of the characters offers in what is some of the least realistic-sounding dialogue ever to besmirch a screenplay.

Benson is very young, skinny, gawky and oily -- a boy in the fullest wonk of adolescence. But even with screamingly bad lines and a face that looks as if it's covered with margarine, Benson has a disproportionately large amount of sincerity and charisma for a teenage boy, and he projects a likable dignity even when flailing and squeaking through the worst pubescent discomforts.

Glynnis O'Connor, in the role of Bobbie Lee, Billy Joe's love interest, has the worst job in the film, having to conjure a big ol' wad of conviction delivering teenage "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof" runoff like this memorable gem:

"I'm a brain, but ah'm a body, too, James, with desires, and somebody better pay attention to that. Mah blood is racin', and mah ample breasts are burstin.'"

Wow, and she ain't but 15. Tennessee Williams, if he hadn't already drunk himself to death, surely had reason to with this kind of tribute.

The teenagers are bored hicks with hot pants on a sticky Mississippi summer. Benson, who is shirtless through a lot of this movie and covered with sweat drops the size of quarters, brings a nicely infectious enthusiasm to even the most mind-blowingly retarded lines, with his voice full of honking and horny teen musk. He successfully epitomizes being a Good Kid without being a total milquetoast and slanting off into abject gooberdom. No boy actor until River Phoenix revealed more sloppy emotion than Robby, especially during the Big Revealing Scene before the suicide.

He's a weepy-eyed mess when he says "I love you" -- what else could teenage girls want? Not much -- this movie revealed the power to make the young girls cry that was to be Robby's ticket as well as his undoing.

Benson's next landmark effort was "One on One" (1977), which he co-wrote with his father, screenwriter Jerry Segal.

The film is a dumb and clumsily formulaic "Rocky" retread for the Clearasil demographic. Robby stars as a naïve, squeaky-clean high school basketball star who goes to college in the Big City and encounters all kinds of moral ambivalence.

The screen is filled with lingerings on Robby's delicate face and cheesecakey body shots of him in super short-shorts and long tube socks pulled up to the knee. Despite his abject geekery, hot, mature women come on to Robby incessantly through the film in a way that could only be imagined by the actor's dad: "You got great legs. Really sexy legs. I'm not kidding."

There is an Evil Coach who wants Robby to give up his scholarship, blah blah blah, and a sexy older girl (Annette O'Toole) who tutors Robby and naturally has to fall for him, even though he represents the odious Jock World and she is an Intellecktual.

There are various obligatory scenes: Hick boy Benson is taken clothes shopping by a teammate and gets all pimped up in a bell-bottomed denim ensemble with wide-collar silky shirt. There is an actually hilarious spazz-out scene wherein one of Robby's teammates gives him some uppers and he yodels and squirts around the court like Jerry Lewis. There is the L.A. party scene, wherein Robby watches in shock as creepy party people writhe and vomit and levitate. "They got straws in their noses!" Benson shrieks. Jeepers!

His ultra-naïveté is lamely unbelievable, but it informs the viewer that Robby Benson is the anti-James Dean: Robby is always articulate and goofily happy, unless being dogged by a clear and present evil. He's a kindhearted, sensitive dorkwad who's never embarrassed or ashamed. While James Dean was a mumbling, depressed, Aryan teen philosopher-king sophisticate who seemed to know all the answers, underdog Robby never knows anything -- he's totally wet behind the ears. His film roles seem always contingent upon his undergoing a continual process of childlike discovery and then triumphing with his goody-two-shoes-ism intact despite onslaughts of worldliness and corruption.

At the ending, Robby's superior ballplaying obviously saves the day. The fans flood the court and put him on their shoulders.

Robby Benson gets the satisfaction of telling off the bully (oh, the joys of father-son dialogue writing): "You hung in there like grim death and I admire you for it," oozes Mean Coach, who wants Robby to remain on the team.

"Sir? All the way up with a red-hot poker. I can play anywhere I want now," Robby whispers with his bunny-boy face.

Roll credits, with Robby playin' a little one-on-one hoops with his girlfriend and ... hey, where did all these little kids of all colors come from? Well, come on! Everybody gets to play basketball with Robby Benson! The camera is trained on the hoop with the sun going down behind it as fast-cut edits show balls being sunk again and again. The sun glares into the lens in two white glowing rings, then ... stop action! A ball is stopped mid-hoop, eclipsing the sun perfectly! Light shines behind Robby's basketball in a perfect aureole! "Love conquers a-a-a-all," wail Seals and Crofts, with lyrics by Paul Williams. Now that's some delicious American cheese.

Critics didn't think so. Many stooped to flat-out character assassination.

David Ansen, reviewing "One on One" for Newsweek under the headline "Doe-Eyed Dribbler," had this to say:

"The less-than-convincing love story, unfortunately, brings out Benson's delusions of grandeur as a scriptwriter ... A similar protest could be lodged against Benson's overly ingratiating performance, which makes innocence look like a form of retardation. Cute as Bambi and twice as smarmy ... Benson seems destined for one of the most protracted adolescences on the screen (by 40 he should be ready to play psychopaths)."

Gary Arnold of the Washington Post flamed Robby with "'One on One': An Unhip Hoopster":

"[In] this poorly rationalized, wish-fulfilling starring vehicle ... Benson seems to perceive himself as a romantic heartthrob and sentimental darling ... The process of disintegration is built into Benson's self-righteously sentimental conception of Henry, the kid underdog ... Benson tries to have his cake and eat it, precisely the indiscretion avoided by Sylvester Stallone as Rocky, whose modesty made his fairy tale success more appealing. Benson also seems prone to vastly overrate his sex appeal. Here again he might have taken a useful cue from Stallone, who really has a potent sexual presence but probably enhanced it among both men and women by matching Rocky with a modest, ordinary girl like Talia Shire's Adrian. Some people have the common touch. Other people merely flatter themselves that they have it while groping around for it. At this juncture Benson is still an amateurish groper ... Really, Benson is going to have to learn how to moderate his fantasies if he expects us to keep a straight face."

(Ouch. To think there was ever a time when Stallone was a Paragon of Humility.)

And then, in 1978, there was "Ice Castles," the film for which Heartthrobby Robby will be best remembered because it was totally fetishized by preteen girls. This is the one film where Robby gets to act halfway cool -- he's not actually cool, of course, but he's as cool as Robby Benson can get in a movie that's built around a romance with a blind figure skater and that features a Marvin Hamlisch-Melissa Manchester soundtrack.

Robby plays an aimless young quitter who bags medical school and his hockey team -- the one thing he doesn't give up on is gurl Lexie (played by skater Lynn-Holly Johnson), when she goes blind after a triple axel by hitting her head on some patio furniture.

"Look at him: He's a beautiful woman," said my spouse, while watching this film, and he was right -- with his long black hair and blue eyes, Benson could have been Charlie's newest Angel, from the Upper East Side.

Robby tries hard to have some teeth in this one -- he slurs his words to make himself sound tougher and more rustic. In the obligatory cheesecake scene, Robby has a phone conversation with his girlfriend while wearing nothing but white box-hugging boy panties that leave nothing to the imagination. A viewer wonders if Benson demanded this bod-shot in his contract, it is so strangely placed in the film -- "All right, all right already, Robby, we'll put your taut groin into the phone scene. Jesus."

Robby emotes a lot in this film. He watches all of Lexie's skating routines with a wet-eyed, heart-in-his-throat expression: Every little girl's fantasy of a boyfriend's face while watching them ice skate. It would be convincing were it not for the fact that no real young man would ever be capable of making that face without taking a lifetime of shit from his friends.

Still, in the big hollow sugar Easter-egg world of that movie, Robby Benson is perfect. He owns it. He plays the drippy, pansy-ass part on both feet like a man-boy with solid conviction. He might make you squirm, but that's your problem. Resistance is futile -- Robby did his job and gave 100 percent, and that is all we can reasonably ask of any actor. We can't demand that they perform in a style that is less cringe-o-delic.

Reviewers hated this movie, too, but it is a Hollywood tearjerk-template classic. It remains a touchstone of childhood in the '70s for an enormous number of American girls who loved the bejesus out of it, and Robby Benson best of all.

An interesting Benson-as-adult role is in the really clunky, dreadful film "Tribute" (1980). Robby plays the uptight, angry son of hammy, womanizing old Broadway hack Jack Lemmon, who gets a Medical Diagnosis at the film's beginning, giving him X amount of time to live. Mandate: Snitty, tight-assed Robby and rascally, good-time-Charlie Dad must connect before Dad dies.

This movie is a doomed wad of sentimental, ego-barking horseshit, for which I blame Bernard Slade, who wrote the stage play and screenplay. Even Lemmon is sucking air, despite his enormous skill -- probably because he was unable, after winning awards for the role onstage, to tone down his massive scenery chewing sufficiently for the intimate medium of film. Benson plays against type as a totally charmless cretin and does a pretty good job, considering that he is violently miscast and doesn't get to use any of the tools in his bag of charisma tricks. When he's playing angry, he has a tendency to go into a cartoonish, roaring voice that I can only imagine came in handy in 1991 when he was the Beast in Disney's animated "Beauty and the Beast" -- even when having ugly pangs of rage, Robby is still a bit on the cuddly side.

This is a movie only Gene Shalit goes down on the record for having liked, at least on the video box, which leads me to the conclusion that Shalit can either be bought for a six-pack of Milk Duds or has the worst taste in the history of American film critics.

In "The Chosen" (1981), based on the book by Chaim Potok, Benson plays a Hasidic boy who befriends a reformed Jewish boy (the consistently admirable Barry Miller) during World War II. I think Benson does a lovely job in this film. For the character of Danny, he developed a very thoughtful and interesting arrogance and self-composure. You can tell he did a lot of nice homework on the insular nature of the Brooklyn Hasidic community; he built Danny without standoffishness, but with an assured difference.

His enthusiasm is naïve, as usual, but (for once) this is totally appropriate to the role. There is a nice moment when it is revealed that he is already intimately acquainted with his new friend's father, a scholar who has been suggesting books for him to read at the library. He looks shaken by excitement, almost terrified at how his hermetic world is suddenly expanding. You can tell, in this moment, that Benson, though he doesn't pull off subtlety with much subtlety, has a proper respect for subtlety. This alone is almost enough to make him a good actor -- added to his spooky good looks. He is likable and compelling in "The Chosen"; the religious nature of his character is a great excuse for the Glow of Wonder in his eyes.

The bumpy friendship between the two boys is very sweet and convincing. Miller, who plays Benson's radical friend, is an underappreciated young actor of the same generation -- he turned in some fine performances in "Fame" and "Saturday Night Fever" but never hit the big time, because, unlike Benson, Hollywood didn't want to see him in his underpants.

A fairly wretched example of Benson's later efforts was "Harry and Son" (1984), in which he plays the twee-spirited son of curmudgeonly, blue-collar Paul Newman -- a diametric switcheroo on his father-son dynamic in "Tribute." Robby plays a guy who is so ridiculously enamored of his Dad that it suggests some kind of gay Oedipal complex.

"Harry and Son" was directed, co-written and co-produced by Newman, which is the main problem -- dear Paul, while a totally engaging screen presence, was wise to focus his future energies on salad dressing. This film almost feels as if Newman, like Tom Sawyer, wanted to see his own funeral, with everyone beating their chests and weeping about what a wonderful guy he was.

He does Robby no favors, letting him turn in a wildly overwrought and cheese-baked smiling-through-the-tears performance with gagging saccharine overtones. A better director might have raised an eyebrow at Robby and hollered, "Knock it off with that Lifetime Television Housewife Emoto-Porn shit! Act like a man with testicles!"

Critics were less kind.

The hilarious Rita Kempley of the Washington Post wrote in her review that "Harry and Son" was "a love story for guys with quiche on their breath," and that Benson's oversympathetic character "makes John Denver look maladjusted." She went on:

"Benson, though he tries his durndest, is egregiously miscast as the pious young hunk. You can stuff him into a torn sweatshirt and tight jeans and put him in a sex scene with a nymphomaniac, but that don't make him Tom Cruise ... let's face it, he's about as sexy as white socks. Attractive, maybe, but sexy, el zippo. Richard Gere in a dual role as both Harry and Howie [the Newman and Benson roles] is the only way this film could work. Otherwise there's entirely too much Sensitivity going on. And as we know, Gere has none ... [The film is] like being stranded at the Friendship rack in a Hallmark card store."

Richard Schickel trashed the movie, and Robby, for Time:

"As a director, Newman has set himself two obstacles: one is his own powerful presence as an actor; the other is Robby Benson's lack of one ... Still, Newman is inevitably a force to reckon with, and that makes his casting of the feeble Benson the more surprising; surely he knows he can hold the screen against a real actor ... Benson is one of those performers who appear to be playing for the mirror instead of the camera; nothing interferes with his pleased self-contemplation."

And that, as they say, was pretty much that for Robby Benson. He lost his leading-man status after being blamed (unfairly) for the mediocrity of his later films. Robby still did a bunch of other crap (including "Modern Love," an autobiographical vehicle which he wrote and starred in with his wife, Karla DeVito, a singer who has the singular distinction of having performed with Meat Loaf), but was largely under the radar until he finally regained a certain legitimacy with his vocal role in "Beauty and the Beast." He now teaches screencraft, does the odd role now and then, and frequently directs TV shows.

I remember (I swear I remember) seeing Benson mentioned on a Web site, maybe five years ago, that was about Hollywood stars who had Bravely Come Out of the Closet. I realize now that site must have been a hoax -- Robby Benson is a married father of two -- but it said he was gay and had bravely come out and told the world he wanted to live openly as a gay man.

The announcement made sense to me, which is why I never forgot it; it made his Michael Jackson gentleness make sense. The site featured a vintage picture of Robby wearing overalls and no shirt, smiling his shy-girl smile with sunlit eyes in what I thought was a field of yellow daisies.

I had a gorgeous, baby-faced male friend who was an infantilism pinup boy in his late twenties ("infantilism," in this context, means a fetish in which adults dress up like babies and are changed and pampered by other adults, with large high chairs and other oversized, baby-centric fetish apparatus.) There would be shots taken of him in diapers or footy pajamas, sucking his thumb or a bottle. I realized that the picture of Robby Benson on this Web site looked exactly like my friend in one of his infantilism shots. His face was too innocent -- it was innocence way past the age that there should be that level of innocence in a face. It looked unsettling and perverse, like baby clothes on a grown man.

Aha, I thought -- that's why grown men hate Robby Benson, and only the little girls understand. It wasn't his acting, per se, but his act.

Robby Benson seems to be a question of values. He was from a pre-MTV era; "coolness" was unusual, then, and now it is a staunch corporate requirement of everyone from the age of 4 up. OK, Robby wasn't cool, but why is that a thought crime? He gave everything he had on the screen -- he was just one of those people whose best wasn't good enough, at least in the eyes of the adult world. His biggest flaw was an excess of cute ingenuousness, which isn't so bad when you think about it. Some people just can't help being children all their lives.

Shares