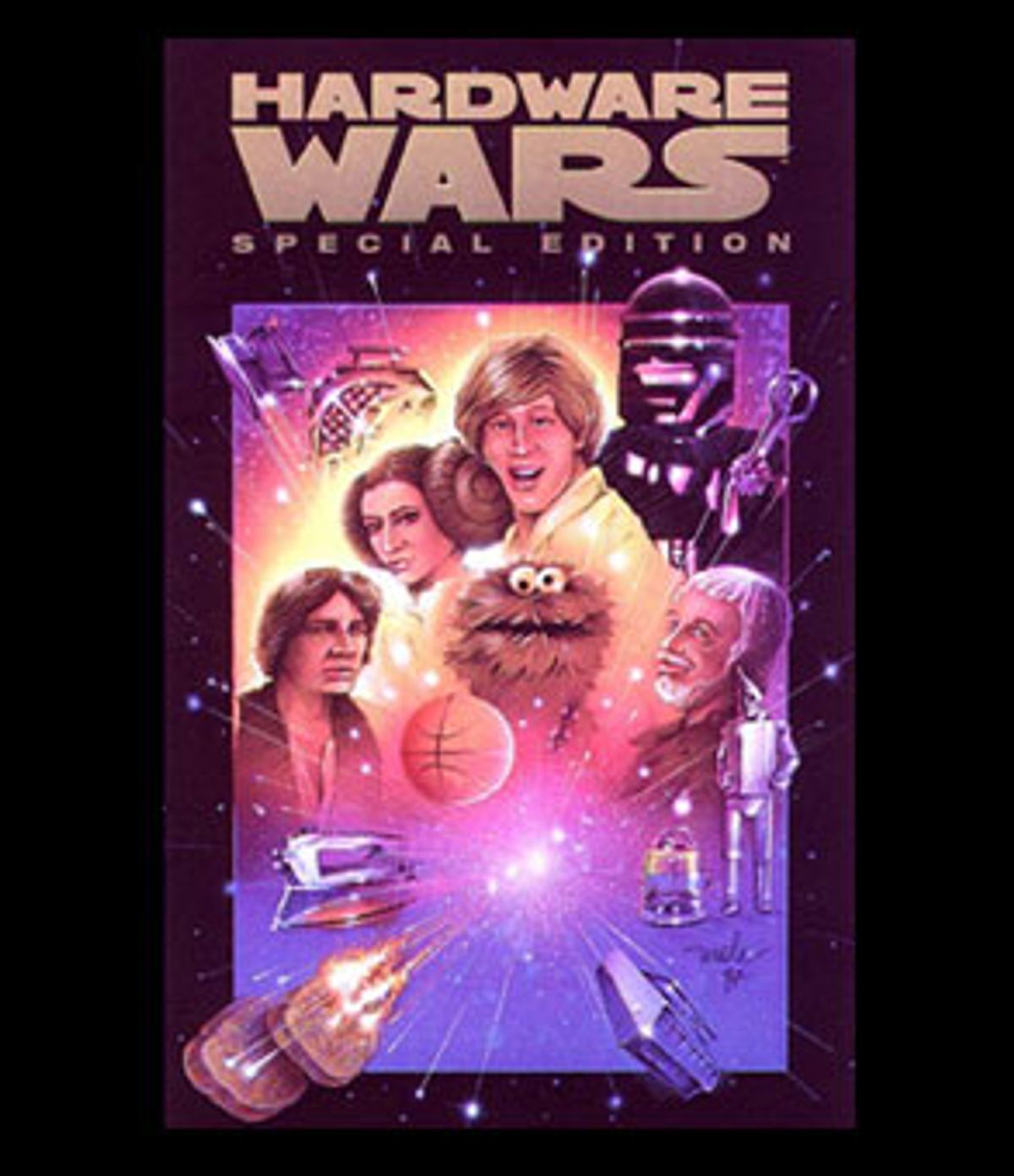

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away -- well, in an abandoned French laundry in San Francisco in 1977 -- a group of rebel filmmakers equipped with only a well-stocked toolshed and a super-8 camera set out to spoof what was becoming the greatest fantasy-film franchise of all time. The resulting parody was a short film called "Hardware Wars," and it stuck it to "Star Wars" in every way possible (or at least in every way that was possible in 12 minutes of running time on next to no budget).

Steam irons and toasters suspended by clearly visible strings were the spaceships, a basketball was a planet on the brink of destruction, and the robot Artie Decko was a defunct vacuum cleaner. As George Lucas touts the digital back lot on which his current "Clone Wars" trilogy is being made, "Hardware Wars" only becomes more poignant. With its release on DVD, this "sprawling space saga of romance, rebellion and household appliances" has returned to remind us just how funny crumpled tinfoil can really be.

"Hardware Wars" was the brainchild of writer-director Ernie Fosselius, who already had an array of satirical short subjects under his belt. The most notable of those was "The Hindenburger," which depicted a flying Big Mac bursting into flames over a cardboard New Jersey while a spastic radio announcer (Fosselius) shamelessly decried "the humanity of it all." Documentary filmmaker and author Michael Wiese got behind "Hardware Wars" as its producer.

"I used to hold these shadow-play parties in my loft," Wiese recalls while taking a break from scouting locations in Indonesia for an upcoming film. "One evening Ernie came over and performed an impromptu shadow play of 'Jaws,' which he just made up on the spot. He was hilarious.

"We had both already made a handful of short films," Wiese continues, "so we talked about doing a film together. At a Chinese restaurant, while waving the condiments and chopsticks over his head like spaceships, Ernie pitched me a parody of Hollywood coming attractions that would take on big-budget special-effects movies. He said we could use household appliances for spaceships. Always one to stretch a dollar, I saw a great opportunity for doing more with less."

With an $8,000 budget supplied by Laurel Polanick (who was also the film's costume designer), "Hardware Wars" was shot in four days in bars, beaches and garages around the San Francisco Bay Area. Surprisingly, production was started only a short time after "Star Wars" was released. Although single-screen theaters across the country had lines wrapping around the block to see the science-fiction spectacular, nobody in the "Hardware Wars" cast was aware that they were poking fun at what would soon become an enduring cultural icon.

"I had no idea what Ernie was talking about," Scott Mathews says after a mix-down session at his Mill Valley, Calif., recording studio. "I'm just starting to get it now."

Mathews donned a lopsided blond wig for the starring role of Fluke Starbucker. Today he is a platinum-selling record producer who has worked with everyone from Barbra Streisand to John Lee Hooker and even an Oakland indie rock band named for his "Hardware Wars" character.

"I think a lot of the charm of that movie is the fact that we didn't really know what we were doing," Mathews adds. "It was cinéma vérité at its finest. I'm sitting there spaced out and cracking up in some of those scenes."

Cindy Freeling, who played Princess Anne-Droid with cinnamon rolls attached to her head, was equally oblivious to the "Star Wars" phenomenon. "I was in an altered state when I saw 'Star Wars' for the first time," she confesses. "It was the '70s, you know. When I went back and saw 'Star Wars Special Edition,' it dawned on me why we had all of this stuff in 'Hardware Wars.'"

From its cardboard sets to the costumes, "Hardware Wars" is an amazing facsimile of its source material, despite obvious budget and time constraints. Fluke, the Princess, Oggie Ben Doggie and Ham Salad all look like slightly off-kilter versions of their "Star Wars" counterparts. "One hundred percent of any of that effect goes to Ernie and his direction," Mathews says.

Another coup for Fosselius was getting veteran voice actor Paul Frees to perform the film's "coming attractions"-style narration. Frees' deep tones can be heard in such film classics as "Some Like It Hot" and the original "Time Machine" as well as a plethora of cartoons, commercials and movie trailers. Producer Wiese still feels the impact that Hollywood's "Man of a Thousand Voices" had on their short: "His voice is so rich that you actually think you are seeing 'incredible space battles' when in fact it's only a Fourth of July sparkler."

After "Hardware Wars" was released, it became the same kind of success in the short-film market that "Star Wars" was among major motion pictures. In 1978, the little movie grossed $500,000, placing it among the most successful shorts of all time.

Over the years the usually litigious Lucas has actually expressed his enjoyment of "Hardware Wars," calling it a "cute little film." It's the only non-Lucasfilm product to be sold in Star Wars Insider magazine. The short enjoys the same semi-endorsed status as the subsequent subgenre of homemade "fan films" to which Lucas has recently given the nod, even hosting a Sci-Fi Channel special about them. Fosselius' space-toaster epic, with its gutsy, zero-budget approach, is probably just as much an inspiration for many of these Jedi-addled amateur filmmakers as Lucas' two trilogies.

Despite Lucas' blessing, Wiese got a different reaction from a group of 20th Century Fox executives when he showed them his movie.

"A meeting was arranged with Alan Ladd Jr., who at the time was the head of Fox," Wiese recalls. "I went down to L.A. with my 16-millimeter print of the film. I think it was the first time I'd been in a studio, and I was very nervous. I was ushered into a super-plush screening room with the huge overstuffed velvet chairs. Mr. Ladd -- 'Laddie' to his friends -- was seated, and behind him were three lawyers in expensive suits. It was the worst screening I've ever endured. No one made a sound during the movie. Someone coughed once and I thought it was a laugh, at least I hoped it was.

"After the screening, Laddie asked me, 'Well, kid, so what do you want us to do?' I said, 'I want you to show this with 'Star Wars.' You know, make fun of your own movie!' He said he'd get back to me, and I'm sure he will."

After the success of "Hardware Wars," Wiese and Fosselius resisted the temptation to produce more sci-fi spoofs. "At one time, someone did offer to finance a full-length feature of 'Hardware Wars,' but we passed," Wiese says. "We always knew it was a one-joke movie and wouldn't sustain that length. Of course that didn't stop Mel Brooks from 'quoting' us -- some might say ripping us off -- with 'Spaceballs.'"

Pyramid Films, the distributor of "Hardware Wars," later released a "Close Encounters" parody called "Closet Cases of the Nerd Kind," but the "Hardware Wars" crew was not involved with it. Instead, Fosselius turned his biting wit toward Coppola, writing and directing a sendup of "Apocalypse Now," titled "Porklips Now." The film lampoons "Hearts of Darkness," Coppola's longer "Apocalypse Now Redux," and DVD commentary tracks, all before any of those things actually existed. It was also the last film directed by Fosselius.

Over the years "Hardware Wars" was relegated to being a fond celluloid memory -- until 1997, when Lucas released digitally altered "special editions" of his original "Star Wars" trilogy as a way of showing off Lucasfilm's new special-effects technology and hyping his upcoming prequels. With "Star Wars" invading the public consciousness again, Wiese decided it was time for a special edition of "Hardware Wars," with even more Home Depot bric-a-brac digitized into each frame.

"Serendipity brought some 'Hardware Wars' fans, who were seven, nine and 12 years of age when the original came out, to my doorstep." Wiese says. "They said they would like to work on a special edition and had some ideas. I thought they were terrific. It didn't hurt that they also worked at Digital Domain [one of the leading effects houses in Los Angeles] and could sneak in there nights and weekends to render our stuff."

Cindy Freeling attended a screening at the San Diego Comic-Con to promote the special edition and discovered a cult following she had never known about. "It was unbelievable," she says. "The room was jampacked. There were people flowing out into the hall. The audience knew every single little detail of the movie. I've certainly seen 'Hardware Wars,' but I don't have every frame memorized. Whenever a 'special defect' would come up, the whole audience would start cheering and clapping. They knew right when it was happening."

Despite the fan reaction, not everyone was happy with the new version. "Ernie [Fosselius] was not involved with the special edition," Wiese says candidly. "He didn't like the approach, and asked that we put a 'Not Approved by Ernie' label on the videos, which we did. His notion -- and I think, in retrospect, he was correct -- was that the new scenes should not have been so highly rendered as they were, but cheesy and funky in keeping with the original."

For the new DVD release of "Hardware Wars," Fosselius himself worked to restore his revered satire to its original lack of grandeur, but he found that the studio technicians assisting him were as clueless about his film's intent as those Fox execs were in the 1970s.

"There's a great inside story about that," Scott Mathews says, recounting a recent conversation he had with Fosselius. "When Ernie was transferring all the old footage from the original print, they had all this amazing gear where they could embellish it. They told Ernie that they could erase the strings! They weren't checking with him: They were telling him they would be doing that in their transfer.

"Ernie tried to explain it. He said: 'No, wait. We put extra strings on there so you could see them! There's more light shining on the strings than there is on the flying iron!' He got a kick out of it. These were the guys that he was collaborating with to make the next phase happen. And they don't even get the premise of the original."

Shares